Candido Camero, a virtuoso percussionist who had a major hand — or more precisely, two of them — in the development of Afro-Cuban music, died today at his home in New York City. He was 99.

His grandson, Julian, said he died in his sleep.

On his 99th birthday, April 22, 2020, WBGO proudly published a Deep Dive by our own Bobby Sanabria, host of Latin Jazz Cruise. We offer it here again, in his memory.

_____________________________________

On July 4, 1946, the dance team of Carmen and Rolando arrived in New York City from their native Cuba. Stars on the island, they were the featured attraction at La Habana’s famous Tropicana night club, where they would thrill tourists with their rumba floor show. These spectacular presentations highlighted a tradition that was born in the solares (tenements), but that had by the 1940s been adapted to a nightclub setting for tourists.

The rumba, born of the fusion of southern Spanish song and dance with West African-rooted drumming, has deep roots in the cities of La Habana and Matanzas. Its earliest form — the slow Yambú, which was and still is played on cajónes (empty wooden crates) that dock workers would utilize as substitutes for drums in the late 19th century, when drumming was outlawed on the island — accompanies a male and female figure dancing, mimicking the movements of a rooster and a hen.

The next step in the rumba’s evolution became known as guaguancó. Its tempo is brighter, with a percussive melody played by congas that accompanies the visual dialogue between a male and female dancer. Its vocals represent Cuba’s cultural fusion between Spain, Africa and the Middle East. Finally there’s the up-tempo colúmbia from Matanzas, with its virtuosic display of solo male dance and drumming. Altogether, the rumba is a rich tradition that has spawned generation after generation of virtuosic Cuban hand drummers.

One of those drummers came to New York with Carmen and Rolando as their accompanist. Not only would he spark a successive wave of soon-to-become-legendary conga drummers that would begin arriving from Cuba to the States, but he would also revolutionize the way the instrument is played by developing the techniques that everyone utilizes when they play congas today.

His name is Candido Camero Guerra, and he was born 99 years ago today, on April 22, 1921, in the barrio of Havana known as El Cerro. “My barrio in La Habana, El Cerro, has its own saying, El Cerro tiene la llave,” he says. “‘El Cerro has the key.’ Cerro means ‘hill,’ but in this case it’s also short for ‘cerrejo,’ which means a latch. So people from there say we have the key to the latch.”

The same could be said of Candido and his relationship to conga drumming. An innovator on his instrument, an NEA Jazz Master, and one of the most widely recorded percussionists in jazz, he has been on a first-name basis with several generations of musicians and fans.

My own relationship with him goes back to 1980, when we both played a lunchtime concert at the World Trade Center, in the orchestra of famed Cuban pianist Marco Rizo. Over the 40 years since, we’ve played together literally hundreds of times, and become close friends. (The quotes in this article come from our conversations over the years, translated from Spanish.)

Danzón in the House, Rumba in the Yard

Candido — “The name means candid, simple, purity, white, innocence” — came from a musical brood. Most members of his family played a variety of instruments. “But except for a few,” Candido explains, “most of them were really amateurs.”

Music was always a central feature of the birthday parties for Candido’s six uncles from his mother’s side of the family. “We had a huge house,” he says.

It had a living room, a separate dining room and about five bedrooms with a large open-air patio in the back. My uncles lived there, and as each one would get married, they began leaving. My grandmother always celebrated their birthdays by hiring a charanga orchestra (a Cuban dance band with violins and flute), and they would play in the living room. I remember them well, it was called Orquesta Cartaya, named after the leader who was a violinist. During their breaks, everyone would move to the patio, where the rumba would start. It was non-stop music all day into the evening.

Candido embarked on his journey as musician at age four. “My first inspiration was my Uncle Andrés,” he recalls. “He was the bongocero of the Septeto Segundo Naciónal. Alfredo León was the leader and tres player (the mandolin-like guitar of Cuba). He was the son of another famous Cuban singer, Bienvenido León. The musicians were from the famous Septeto Naciónal de Ignacio Piñiero.”

When asked why this group was formed, Candido erupts in laughter: “Let’s just say that the musicians didn’t get along with Piñiero.” During this time, the son was becoming the rage in La Habana, slowly over taking the sedate, elegant danzón in popularity. The son originated in the eastern part of the island (Oriente) and came to Havana in the late 1890s, bringing a fusion of Spanish-influenced harmonic and melodic content and the West African-rooted clave rhythms, with its emphasis on the bongó. By the 1920s, it was taking Havana by storm.

My uncle would take me to see all the great son groups at the time. I would go to the rehearsals of La Naciónal Juvenil. The bongócero there was a guy named Abuelito. Tremendous! It was funny, because in those days you literally had to go the local precinct to get a permit so you could rehearse during the day or throw a party at someone’s house. You see, it was technically considered an infringement on the neighborhood because you would be making noise. You had to let the neighbors know, then go to the police and get permission. It was even more hilarious when the then-president of Cuba, Machado, outlawed the use of the bongó. He considered it a ‘primitive’ instrument, but that was just an excuse. He was offended by some of the double-meaning soneos (improvs) that soneros (singers of son) would make up about him and his administration.

Candido’s precociousness would lead him to constantly drum on tables in the house, earning frequent scoldings from his mother, who feared he would hurt his hands. Luckily, his maternal grandfather, Juan, would intercede. “‘Leave him alone!’, he would tell my mother. ‘You will see. One day he will be famous.’”

“My uncle Andrés asked me if I wanted to learn how to play el bongó, and of course I said yes. He went and took two cans of condensed milk, put skins on them, and put them together. That was my first instrument. He began teaching me by having me sit in front of him with my tin can bongós while he had his set. He would play a short phrase and ask me to repeat it. That’s how I began learning how to play.”

But the bongó was not the only instrument in the cards for young Candido. Today he is known not only for his rhythmic inventiveness on congas, but also for his unique melodic approach to that instrument. The root of that melodicism began with a birthday gift.

“For my eighth birthday my father gave me a miniature tres. Just like my uncle, my father would show me something and ask me to repeat it. At the age of 14, my grandfather would begin to show me how to play the acoustic bass. In those days, bass strings were expensive. We would use fishing line as a substitute and put rosin on it.”

Candido began playing tres with local groups, a memory he savors. “I used to go to the Playa Marinao beach resort all the time, because they would have impromptu rumbas there,” he says.

That’s how I encountered others who were my contemporaries, like Patato [Valdés], Mongo [Santamaría], Francisco Aguabella and characters like the famous Sylvio Sheung, whom everyone knew as ‘Choricera.’ He used to have this beat-up set of timbales that were held together with wires. He would do a show with this little group. He would screw in a red lightbulb into a socket above him when he was about to play. It was funny, because he always carried that lightbulb with him. Imagine if he would have lost it, or it would have broken! [Laughs] I remember his conga player. He was very old and very ugly. His nickname was ‘Cara Linda’ (beautiful face). We used to laugh and say, ‘That guy is uglier than a dark evening.’ But wooo, he kept time like a metronome.

Birth of the Conjunto and Candido El Conguero

Although Candido is most associated with the conga drum, it was the last instrument he would learn how to play. At this time, the legendary blind virtuoso of the tres, Matanzas-born Arsenio Rodríguez, was revolutionizing the way the son was played. At the time, the standard of performing the style was with a tres, a guitar, a bass, one trumpet, a bongocero, a primera voz (lead singer) playing clave, and a segunda voz (backup singer) playing maracas. Collectively this style of ensemble was known as a septeto. It would be radically changed by Arsenio whose sobriquet became El Ciego Maravilloso (The Marvelous Blind One).

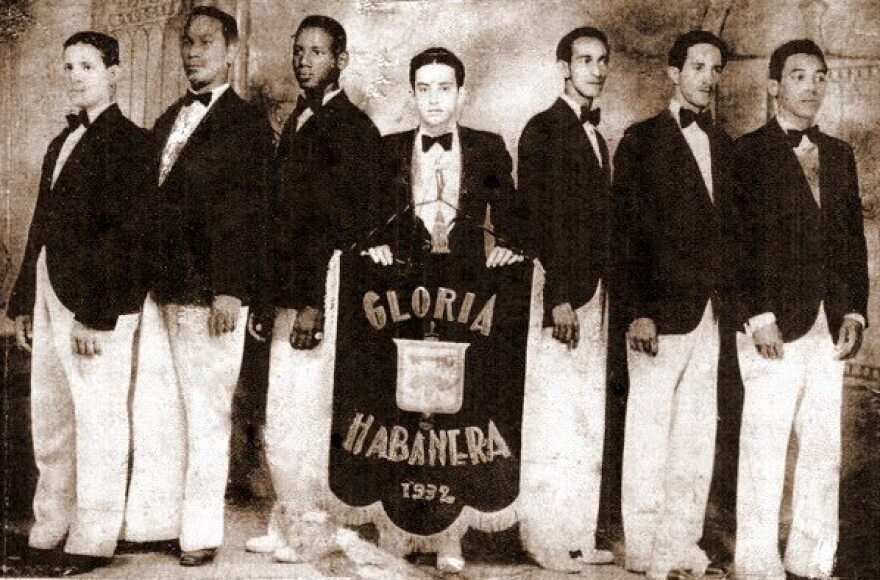

Rodríguez added piano alongside the guitar, and also a second and then third trumpet (and sometimes a fourth), using written arrangements in contrast to the septet tradition, wherein the lone trumpet would ad lib. Then he added a conga drummer to the band on a regular basis. “Others had done it before,” say Candido. “I saw a group called Septeto La Llave use someone playing a conga in the early ‘30s, but not on a permanent basis. Arsenio made it a permanent part of his group.”

With the lower tonal center of gravity and percussive funkiness provided by the conga drum, the bongócero could in effect play with more intensity, making use of the cencerro (handheld bell) in the montuno (vamp) section as a standard rhythmic device. The increased harmonic palette provided by the piano added to the tres’s guajeos (arpeggiation of chords in clave), and bass lines could also become more complex. Rodríguez’s use of written arrangements — giving specific parts to his trumpets, layering line against line to create tension and release in the montuno section — created the mambo horn concept.

Rodríguez’s emphasis on making the montuno the main part of the song, in order to feature the improvisational skills of both singer and soloists — inspired bandleaders as well as putting dancers into a frenzy. But beyond that, Rodríguez’s use of African-based themes in his compositions, as well as an African rooted drum — a drum that had previously been found only in annual street carnival celebrations, African-based religious ceremonies, and in the rumba tradition — made it part of the bandstand experience. This became a unique social statement and a source of pride for Afro-Cubans.

It was here that Candido made a life changing decision. “I saw Arsenio’s group and saw the writing on the wall,” he says. “I didn’t read music and I knew that the groups would all start to convert from the septeto to the conjunto format. In the conjuntos they started to use arrangements, and I couldn’t read music. I figured I wouldn’t be able to keep up as a tresero or bassist. I had played congas ever since I was kid, when I would participate at the rumbas in my home. I decided that I would begin to concentrate on playing congas professionally.”

Tropicana Nights

Havana’s nightlife was in full swing. Hotels and numerous cabarets were bankrolled by American gangsters who profited from the lucrative gambling, prostitution and liquor trade. The entertainment industry flourished under these conditions. Musicians would also benefit: there was an abundance of work, with each hotel featuring a show band and a small group. Large radio stations like Radio Progresso and CMQ had staff big bands to perform live on the air and accompany guests.

“The first cabaret I worked at was the Cabaret Kursal,” Candido remembers. “I was 22 years old and my salary was one dollar a night. I was playing bongó with the house band and quinto for the rumba floor show for whatever dance team would be featured. Mongo was playing bongó with Bienvenido León Y Sus Leónes at the Cabaret Eden Concert when he got offered a job to go to Mexico with the dance team of Pablito and Lilón. He gave me the job with Bienvenido, and that’s how I got more involved in the cabaret and hotel scene.“

Candido soon made a name for himself performing on conga and bongó at such famed venues as the Cabaret Montmartre, El Faraón, El Sans Souci and all of Cuba’s major radio stations, including a six-year stint with the CMQ radio orchestra and another six-year stint with the famed Tropicana Orchestra. (He helped inaugurate the club in 1943, playing bass as well as bongó and conga.)

At the Tropicana we did a big show which featured Chano Pozo, called ‘Conga Pantera.’ I knew Chano from playing in his group Conjunto Azul, where I played tres and Mongo played bongó. At the Faraón I met and worked with Chucho Valdés’ father, Bebo. We’ve been friends ever since, and later in the mid 50’s we recorded a tune he wrote called ‘Batanga.’ That was important because it was the first popular piece to use the batá drums in a dance band context.

At Radio CMQ, Candido worked with a show drummer who greatly influenced him. “Salvador Admiral was tremendous,” he attests. “He was very creative and played a lot of things that people would think were just recently invented.”

And jazz played a considerable role in the sound of the clubs. “That was the thing with all of the musicians at that time,” Candido says. “We all were affected by jazz. That’s what made [legendary composer and arranger] Chico O’Farrill move to NYC. He wanted to play jazz.”

Candido’s tenures at the famed Tropicana and Radio CMQ provided him with a wealth of experience in a wide range of settings. From backing featured guests to performing for dancers to playing concert music and big production numbers. The drumset players he worked with inspired in him something that would revolutionize conga drumming.

Two For One

Carmen and Rolando were famed performers whose rumba floor show was a highlight for any attendee to the Tropicana. Highly arranged big band dance numbers showcased the dance team’s virtuosity as they were accompanied by two congueros. Candido, inhabiting the role of quinto player (soloist in rumba) would have to follow their every move, marking their steps with solo riffs in a conversation between dancers and drum while his percussive counterpart would provide the steady foundation. It was the soul of the rumba of the tenements, but in a nightclub setting for the high-rolling tourists and Cuba’s upper class elite. It was inevitable that the dance team would be booked to perform in NYC. But there was a catch. The full percussion section of two conga drummers could not be taken. Candido alone was chosen for his skill as a quinto player.

The promoter told me I would be going, and I started to think. I had begun practicing playing the tumbao (steady rhythm) with my left hand while I soloed with my right, and was making progress coordinating the two. When we were at the airport, I brought with me a quinto and a conga and the promoter began to ask me ‘Why do you have two drums?’ I told him, ‘Don’t worry, you will see.’

On July 8, 1946, several days after their arrival in New York, Carmen and Rolando, accompanied only by Candido, opened a musical revue called Tidbits of 1946 at the Plymouth Theater. The night before, they had performed at the Cabaret Havana Madrid on 52nd Street and Broadway, in front of the Capitol Theater. In the house was the Anselmo Sacasas Orchestra, from Cuba; the Catalino Rolon Orchestra, from Puerto Rico; and Charlie Valero’s conjunto, from Mexico. (Also in the house were the comedy team of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.)

What happened next would astound the audience and New York City’s Latin music community. Carmen and Rolando exploded onto the stage, dancing to the propulsion of an up-tempo guaguancó. It sounded like several drummers simultaneously, but it was all being generated by Candido. As the intensity grew, he marked with the quinto, soloing in his right hand while he played tumbao in his left — all the while following the movements of the dancers.

“The crowd went crazy, and Carmen and Rolando began hugging me,” Candido proudly recalls. “The promoter who had asked what I was going to do with that extra drum came over to me. He smiled and said, ‘I see what you mean.’” Musicians surrounded him, asking how he had performed this musical feat. He smiled and said: “Out of necessity.”

Palladium Nights and Birdland Flights

The stretch of 52nd Street between Fifth and Seventh Avenues was the home of progressive jazz. On the corner of Broadway stood Birdland, named after alto saxophonist Charlie ‘Yard Bird’ Parker, who along with Dizzy Gillespie helped create the virtuosic form of jazz improvising known as bebop. On the next block up, at 53rd and Broadway, was the Alma Dance studios, whose name would be soon changed to the Palladium Ballroom — Home of the Mambo. Candido would soon learn that it was commonplace for musicians to sit in with whomever was playing at either club when they took a break.

Thus a fertile ground was in place for the interaction between Latin and jazz musicians. At its nexus was the Machito Afro-Cubans, a big band under the musical direction of trumpeter (later saxophonist) Mario Bauzá, which had singlehandedly fused Afro-Cuban rhythms and jazz when they were formed in 1939 in the Spanish Harlem (El Barrio) community uptown.

Candido visited the Palladium, and Machito asked him to sit in. He was eventually asked to record on a version of “https://youtu.be/fMsrYUlV4ng">El Rey Del Mambo.” This was Candido’s first recording date in New York, a historic occasion. “But what impressed me was Machito’s band,” he recalls. “There was really nothing that you could compare to it in Cuba. There were so far ahead of everyone, very progressive.”

Keeping pace with the forward thinking of the Machito Afro-Cubans, Candido demonstrated an even more spectacular innovation in percussion at the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem in 1950. While appearing with Puerto Rican pianist Joe Loco’s band, he was the first to perform on three congas, each tuned to a specific pitch.

“I had seen the New York Philharmonic perform, and paid attention to the timpanist,” Candido says. “I thought to myself, ‘I can do the same thing with the congas.’ I began to tune them to a dominant chord so I could play melodies in my tumbaos and solos.”

Evidence of this innovative approach can be clearly heard on the Joe Loco rendition of “Tea For Two.” Candido plays the entire melody on three congas and a tuned set of bongós. He eventually incorporated as many as six tuned congas, though his standard would be three.

“Mañana”

One of the disciples of the Machito Afro-Cubans was trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who had been friends with Mario Bauzá, Machito’s musical director, since their days in the Cab Calloway band in the late 1930s. Dizzy was a champion of the new music, and his enthusiasm eventually led to fabulous experiments like his collaboration with conguero Chano Pozo, which famously yielded the Pozo/Gillespie/Gil Fuller masterpiece “https://youtu.be/v7RMPAABXmk">Manteca.”

Gillespie had heard about Candido, and asked him to sit in with timbale titan Tito Puente’s orchestra at the Palladium so he could check him out. He was suitably impressed. Gillespie had suffered a tremendous loss with the untimely murder of Chano Pozo (by Eusebio ‘Cabito’ Muñoz) on Dec. 2, 1948. He briefly filled that conga chair with a Puerto Rican, Sabú Martinez, but soon turned to Candido, asking whether he’d ever played in a jazz context before.

I was honest with Dizzy. I told him no, but that I knew I could do it if he gave me a chance. At that time my English was very limited. He told me to come down to the Downbeat club on West 52nd Street to sit in with pianist Billy Taylor’s house trio, to play a set and see if I could swing the tumbao to fit in a jazz setting. I did, and he told me to meet him mañana. So I came back the next night to the club and played another set, thinking he would be there. What I didn’t know was that he meant for me to meet him tomorrow at the train station — that they were going on tour with his big band. The club owner at the Downbeat offered me a one-year contract to play with Billy’s trio as a featured performer, and I accepted. We accompanied everyone that was anyone, including Charlie Parker, who used to call me ‘Dido.’ That was my entrance into the jazz world.

When Gillespie returned from the road, his pianist at the time, Wynton Kelly, came looking for Candido. “Wynton began asking me in Spanish what had happened,” Candido says. “I told him, and he started to laugh out loud. He explained everything to me and then both of us started to laugh. I eventually did tour with Dizzy. I was disappointed that I didn’t do that first tour, but that association with Billy yielded my first appearance on a jazz recording and as I said, the experience of accompanying every star in the jazz world opened the door for me to get on many recordings.”

Stage, Screen, Studio

By 1952, Candido was being hailed by jazz critics as the greatest conga drummer to come from Cuba since Chano Pozo. What many failed to realize was that Candido had arrived six months prior to Chano’s arrival New York.

Candido would become the most visible ambassador of Afro-Cuban percussion of his generation, appearing on television with Duke Ellington (on The Drum Is a Woman); on The Steve Allen Show; and with the likes of Pat Boone, Jackie Gleason and Patti Page. I first saw him as a kid, on The Ed Sullivan Show.

He’s appeared on literally hundreds of albums, with such famed jazz artists as Woody Herman, George Shearing, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins, Erroll Garner, Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Stan Getz, Count Basie, Buddy Rich, Wes Montgomery, Elvin Jones, Dexter Gordon, Stan Kenton, Lalo Schifrin and Charles Mingus. (The list goes on and on.) He can also be heard on albums by Ray Charles and Quincy Jones. Combine that with his soundtrack and studio work, and he is one of the most recorded conga players in history, along with Ray Barretto and Ray Mantilla.

Ever the innovator, Candido was approached by Puerto Rican drum maker Frank Mesa in 1957. “Frank made the first mass-produced fiberglass conga drums, and he made me a set. I really liked them and am proud to say I was the first one Frank approached to play them. Today I am a proud LP endorser, but back then Frank was the only one making fiberglass drums. Those Echo-Tone fiberglass congas and bongós are now collector’s items.”

Candido’s contributions to the world of percussion were recognized in 1960 and again in ’72 by the World Book Encyclopedia, which featured a picture of him in the heading under conga drum. His spectacular solo work was featured on the Broadway production of Ellington’s Sophisticated Ladies. In more recent years he appeared on several Grammy-nominated recordings, including a 1986 collaboration with legendary vocalist (and fellow Cuban) Graciela.

In 1979, Candido recorded a https://youtu.be/B85dYk77V-o">disco/Latin House version of Michael Olatunji’s “Jingo” (a hit for Santana), which became a worldwide hit; it has been sampled by DJs the world over.

Millennial Conga Hero and Jazz Master

Well into the 21st Century, Candido amazingly maintained an active schedule of public performances, continuing to travel with the Conga Kings (Candido, Giovanni, and Patato), and serving as an example to the younger generation of living history. In fact, there isn’t a conga player today that doesn’t play something Candido first did. His innovations — in terms of coordinated independence, melodic playing, the use of multiple drums — are the stuff of legend.

In fact, he is the father of the modern multi-percussion set-up — for one thing, he invented the first foot-operated cowbell, which allows a drummer to free up both hands while maintaining the clave or any other pattern. “I had a gentleman at a hardware store make the apparatus to my specifications back in 1950,” he recalls. Look at any percussionist playing today playing in a salsa, rock, pop, or funk context, and you’ll see living proof of Candido’s influence.

For his contributions to the world of jazz and his place in its history, Candido was bestowed the highest honor the United States reserves for a living jazz musician, when he became a 2008 NEA Jazz Master. It’s a fitting tribute to a man who fulfilled the promise of his grandfather Juan, and whose name means “purity of soul.”

I’ve known Candido for 40 years, and among the many things I learned from him is this: “One must not only be colleagues and friends on the bandstand, but off of the bandstand as well.”

Happy birthday, Maestro Candido Camero! Here’s looking ahead to the centennial.

This is a guest installment of Deep Dive with Lewis Porter, our popular jazz historical series. Portions of the article previously appeared in TRAPS magazine in 2007.