As the old line goes, "Jazz was born in New Orleans, but it grew up in Kansas City," so it was appropriate that in 1997, the American Jazz Museum opened its doors at one of the most important jazz crossroads in the world—-18th and Vine in Kansas City. The museum serves as a vibrant performance, exhibition, education, and research space. The day I attended there was a wonderful art exhibit of Frederick J. Brown, featuring his oversized oil portraits of legends like Big Joe Turner, Thelonious Monk, and Etta James.

While it serves to honor jazz as a whole, the importance of the city and the musicians that changed the music here is inescapable. My capable guide was James McGee, the museum's senior manager of community partnerships and events.

The American Jazz Museum builds its story and collection around four cornerstone artists: Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker.

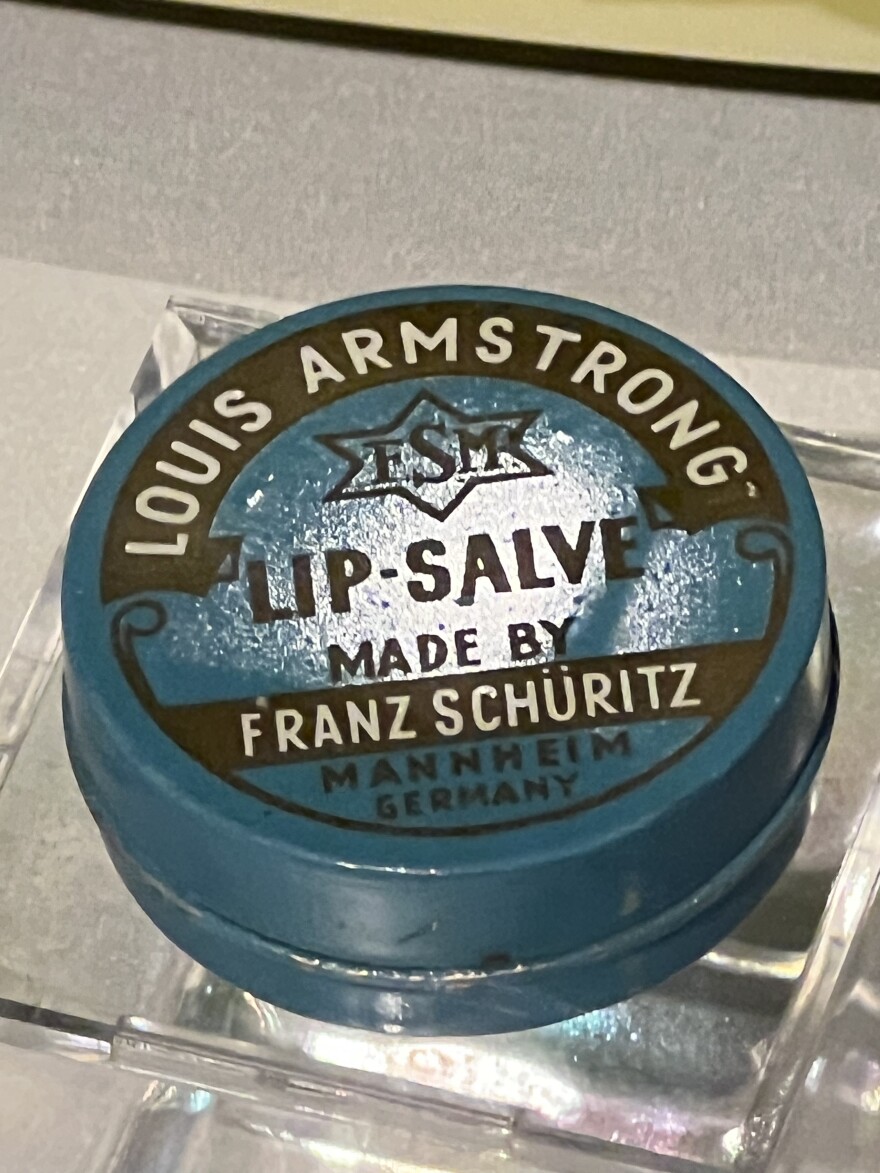

Armstrong did it all. "Pops" was a trumpeter, singer, bandleader, entertainer, ambassador and integrator. James McGee says Amstrong's influence was extremely important all over the world.

"It wasn't just this country. When they were over in Europe during World War II, Louis Armstrong and his musicians were an interracial band. That was propaganda for the country to say hey look America has got its problems but we can come together for this. That was like a weapon for the U.S. in that fight against the AXIS as they were trying to segregate and marginalize people, this band is working together. That was Louis Armstrong. It was a very powerful thing."

While "Satchmo" was attending the school of hard knocks on Basin Street, Duke Ellington was born to two piano players with means in Washington, D.C. Ellington had formal training and after absorbing ragtime, classical, and other genres, created a style of his own with one jazz standard after another. His sheet music, U.S. Stamp, and other ephemera are featured in the museum.

The collection of Ella Fitzgerald memorabilia is perhaps the most impressive in the American Jazz Museum, from a sequined stage dress to a 1945 cover of DownBeat Magazine to her eyeglasses.

The stylish jazz club attached to the Museum, The Blue Room, is one of the few venues in the district that still present live jazz and blues. It is filled with vintage instruments, black and white photos, and mural honoring Kansas City's part in jazz history, including legend Jay McShann.

No story of jazz in Kansas City would be complete without mention of "The Foundation."

"When you walk into the Mutual Musicians Foundation, previously known as Musicians Local 627, you feel the spirits of the ancestors and everybody who came through there. The building was constructed in 1904 originally as a six-unit apartment building. It was purchased in 1927 by the union. The musicians went in and renovated it and did all the work to it to make it a musical hall. So they would do the business downstairs and the rehearsals and things upstairs. That place has been there and stands as it is in 2024 in its original state. There are not many places like that, especially when it comes to talking about jazz."

Noticing that he piqued my interest and that I was not a casual observer, James McGee produced a key and asked if I wanted to walk over to the Foundation, a place where every major jazz artist that came through Kansas City in the last hundred years played there. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie met there. It's not hard to guess my answer. The building itself is nondescript, but when you enter and walk the creaky stars through the ancient union hall, the ghosts of jazz blow right through you.

One of the most enjoyable parts of the visit was McGee himself, steeped in jazz history, Kansas City in his soul.

"I have direct family ties to the area. My mother's side of the family is from Kansas City. We've been here for generations."

The American Jazz Museum in Kansas City and its neighbor, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, are well-worth the visit.