By the early ‘80s, Chick Corea had already worked with Miles Davis, released numerous groundbreaking albums and led various groups, including the popular and influential Return to Forever. Restlessly creative as he would be for the rest of his life, Corea decided to assemble a new group that would reflect his latest explorations on the electric keyboards. The resulting Elektric Band had a few different members initially, but soon settled on personnel that would stay together for the next 6+ years and would set a standard for contemporary jazz: John Patitucci (electric bass); Dave Weckl (drums); Eric Marienthal (alto saxophone); Frank Gambale (guitar). During that period, the Elektric Band released seven albums and toured all over the world. In part because the members became leaders of the own groups and in part because Corea immersed himself in other projects, in 1991 the band cut down to a piano trio (The Akoustic Band) and the group formally disbanded, though they continued to reunite for performances off and on during the next two decades.

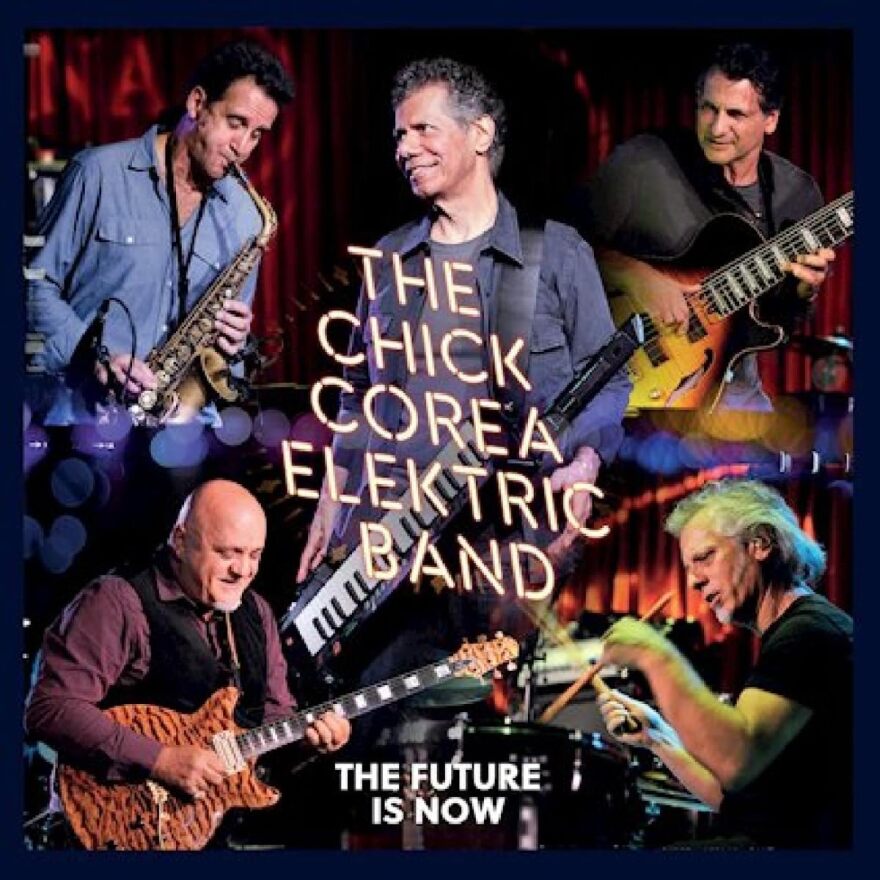

Recently, Candid Records released a box set from the Chick Corea Elektric Band—The Complete Studio Recordings, 1986-1991—featuring all five studio recordings from the group in a five-LP set. In addition, Candid has released The Future Is Now, a live set of previously unreleased material from the reunited group’s performances during 2016 and 2017. That album includes in-depth liner notes from Corea, as well as from all of the Elektric Band members. One of the most influential jazz pianists and composers of his time, Corea died in 2021 at the age of 79, but his legacy looms large among jazz fans and his fellow musicians.

I spoke with Patitucci and Marienthal about their formative experiences with the Elektric Band, as well as about Corea’s outsized influence on their own lives and music.

Listen to our conversation, above.

Interview transcript:

By the early ‘80s, Chick Corea had already worked with Miles Davis, released numerous groundbreaking albums and led various groups, including the popular and influential Return to Forever. Restlessly creative as he would be for the rest of his life, Corea decided to assemble a new group that would reflect his latest explorations on the electric keyboards. The resulting Elektric Band had a few different members initially, but soon settled on personnel that would stay together for the next 5+ years and would set a standard for contemporary jazz: John Patitucci (electric bass); Dave Weckl (drums); Eric Marienthal (alto saxophone); Frank Gambale (guitar). During that period, the Elektric Band released seven albums and toured all over the world. In part because the members became leaders of the own groups and in part because Corea immersed himself in other projects, in 1991 the band cut down to a piano trio (The Akoustic Band) and the group formally disbanded, though they continued to reunite for performances off and on during the next two decades.

Recently, Candid Records released a box set from the Chick Corea Elektric Band—The Complete Studio Recordings, 1986-1991—featuring all five studio recordings from the group in a five-LP set. In addition, Candid has released The Future Is Now, a live set of previously unreleased material from the reunited group’s performances during 2016 and 2017. That album includes in-depth liner notes from Corea, as well as from all of the Elektric Band members. One of the most influential jazz pianists and composers of his time, Corea died in 2021 at the age of 79, but his legacy looms large among jazz fans and his fellow musicians.

I spoke with Patitucci and Marienthal about their formative experiences with the Elektric Band, as well as about Corea’s outsized influence on their own lives and music.

Listen to our conversation, above.

Interview transcript:

Lee Mergner: Let's start with you, John. Do you remember the first time you heard Chick's music? What was it and what was your reaction?

John Patitucci: The first thing I heard was Return to Forever, but the one with Joe Farrell, Stanley [Clarke], Airto and Flora [Purim]. I was a kid and I had a mentor, this guy Chris Poehler, in the Bay Area. He made cassettes of all kinds of music for me. One of them was the first record they did on ECM, which had “La Fiesta” and Stanley played this open solo in the beginning of that.

Then, of course, Light As a Feather. That was a huge thing in our house. We used to blast that record all the time. So much so that my father even knew the melody to “Spain.” That was a big deal. Later on, I did go to see Return to Forever at Berkeley Community Theater in the San Francisco Bay area. I saw the Romantic Warrior tour which had to be around 1975, something like that. It was just insane. I was in high school so that was my first real thing. I got into all the other stuff later on like Now He Sings, Now He Sobs and all that.

That's how it often goes with our generation. We may have started with the fusion stuff, like how with Miles you might start with Bitches Brew and then go back later. How about you Eric? What was your first exposure to Chick as a musician?

Eric Marienthal: It's hard to remember exactly which record. I remember distinctly in high school, probably right around the time I met John, if not before. I was in a quartet in high school when I was a junior. Our quartet was very acoustic. It was saxophone, piano, bass, and drums and we were so into Return to Forever. We transcribed the entire Where Have I Known You Before record. I played all the guitar parts.

John Patitucci: Little did you know you were in for some torture later on.

Eric Marienthal: Exactly. To think that I was able to play even 10 percent of all those notes is a little complimentary to my own talents back then. So I don't really know. Around the same time, 1976, I think, I went to Royce Hall at UCLA to hear Return to Forever and it was mind blowing. It was just incredible. It was big, so it wasn't like the music that I later got into, like John said, the first record, Now He Sings, Now He Sobs and, and some of the early Return to Forever stuff. Then later, the collaborations like The Mad Hatter and Touchstone and those records. If you read Herbie's biography, he talked about the fact that every record that he did, he felt like he really wanted to do something quite different from what he had done before.

It really felt the same way with Chick, where every record you listened to was something that was just so innovative. We, as musicians and as fans, we really looked forward to every Chick Corea record that came out for that very reason. Because it was like, “Oh, wow. What's the cool new thing that Chick's going to come up with?” From those records, it was always like that for me.

John Patitucci: It was amazing with the Elektric Band, since we started out as a trio but we added the saxophone and when Eric was added, Chick would come in with untransposed saxophone parts for the alto. Eric would sight read the stuff and sight-transpose the stuff. Now, it'd be one thing if it was a little melody to a standard, but this was like those insane lines that Chick wrote. And Eric sliced through it. I was blown away by that personally because that was just a lot of written music that was really deep.

Eric Marienthal: Well, right back at you, pal. Not only do you read your butt off, but John would pick up the electric six-string and play it like nobody's ever played before. Then, put that down and play the acoustic [bass] like nobody's ever played that instrument before. It was that and the ability of that whole group when I first walked in, which at first seemed like the most intimidating environment that I could ever have imagined, turned into the most inviting family and environment that was the farthest thing from being intimidating.

John Patitucci: Although I have to say, I remember that first rehearsal as a trio and I thought I was an improviser until that day. All of a sudden, Chick started comping. I always tell my students it was like being in the ring with Ali. I felt like the comping was way better than my solo. I felt like after he played that, the problem was in the trio in for the Elektric Band. At first it, he would blow. Then it was my turn, I have to follow that. It really pushed me, I'll tell you.

You're just getting wasted every tune, so you kind of have to just look at it as a growth experiment. Otherwise, you would jump off a bridge. It was amazing. When Eric first came in, when you hear Chick play like that, and even for Frank, who was like a real blaster on the guitar, once you hear Chick play that first solo in a rehearsal and then you go, “Oh my God, what have I done? What am I doing here?” It's scary because he was such an improviser and so powerful. Some of the intros to something like “Got a Match” or something up tempo, they were just ridiculous. You'd go, “Okay, well, I don't know what I'm going to do now, but I guess I'll have to try to find something, but nothing will be as good as that.”

Eric Marienthal: In the Elektric Band, I took over that unenviable position.

So it actually sort of started as the Akoustic Band and then the Elektric Band?

John Patitucci: No, it was an electric group and an acoustic group. But he was really focusing on the keyboard because he had all these keyboards. We were playing mostly electric. And that's what made me get a six-string bass because it was so insane, all the keyboards. I wanted to play the low notes, and he had keyboards going down to sub-octave levels. I wanted the low notes on the six string and then I had to solo after him, so I wanted that high string. It was really an orchestrational choice that forced me to go to the six-string. It wasn't because I was trying to be cool. I was scared to do it actually, but I figured, “You know what? I think I need something. I need help.”

It was a newer thing then, right?

John Patitucci: Anthony Jackson was the pioneer. He was the real Galileo of the whole thing. He was amazing, but he had such a unique and individual style. I knew I wasn't going to sound like him. Nobody can really sound like him so I went a different direction with it. I think because of Chick’s music, it also funneled me into this other thing. I was really into bebop too. So that became my tenor, the six-string.

Eric Marienthal: You used to talk about that a lot. I would ask you questions about who you were listening to and what was your inspiration in general. And you would say, “I want to sound like a tenor player, I want to play like a saxophone player and create those kinds of lines.” Nothing against Anthony whatsoever, Anthony is a genius but you approached it very much like a melody instrument, never forgetting where home base was. In soloing, it was like another horn player.

John Patitucci: I was just trying to do my best to survive after those Chick Corea solos, so that pushed me towards that.

Now how did you come together? Had you worked with him before and were you and Dave Weckl familiar with each other already?

John Patitucci: No, I didn't know who Dave was. When I first got the gig , I was the first one hired. I said, “Why don't we get Vinnie Calaiuta?” because I didn't know Dave yet and Vinnie and I had played a lot together. He said, “No, no, there's this young guy, like you, he's from St. Louis, but he lives in New York. When I asked Michael Brecker who the greatest young jazz drummer in New York was, he didn't miss a beat. He just said, Dave Weckl,” immediately.” So Chick went and sought him out. He heard him play with Bill Connors and he stole him from Bill Connors immediately.

For me, it came from a jam session. My first road gig in life at around 19 years old was with Gap Mangione, Chuck's brother. One night, when Chuck Mangione used to live in Brentwood, California, in the LA area, in a fancy house in Brentwood, he used to have these jazz jam sessions and he called me to play. Gayle Moran, Chick's wife was there at the jam session playing piano. She went home and told Chick, “There's this kid. I think you might want to hear him.”

Weird things happen. Chick and Gail used to have a Valentine's Day party at their house. Every Valentine's Day, they'd have all these desserts and really cool things to eat and hang. And they would invite certain people to come play and they invited Victor Feldman's trio, which I was a member of, to come play. There I was.

I had really been wanting to play with Chick for several years, but I didn't know any way to get to him. I used to play with Joe Farrell and I said, “Are there any auditions ever?” He goes, “No.” I was like, “Well, how am I going to ever get there?” Well, there I was in his living room playing. That's when he heard me. He heard me play acoustic first. Then he approached me and said, “Do you play electric bass?” And I said, “Well, that was what I started on. Yeah, I do.”

I had to send him some tapes of that. I remember him calling me once and said, “I really listened to and dug all the stuff you sent.” I sent him a record with Clare Fischer and some live gigs from the Baked Potato [club in LA]. He talked to me for, I don't know, 15, 20 minutes and he said he liked it and everything. I was excited. Then when he hung up, I thought, “Okay, well, that's it. I guess he liked it, but it wasn’t enough to hire me.” Then I was kind of like, “I don't know what happened. I don't know what's going on.” Then about a week or two later, he called me. I was at a studio called Weddington Studios near Lancashim on Weddington street.

There was a funny engineer who was a kind of like a comedian. I was in the lounge. We were taking a break from recording and this guy, Wally Grant, came on the intercom. I was in the lounge and I thought he was messing with me. The intercom went on and he said, “Phone for you, it's Chick Corea.” I'm like, “Yeah, great.” Then he calls me back again and he goes, “No, it's really Chick Corea.” Yeah, right. Thanks a lot, Wally, click. Then the third time he goes, “You idiot. It's really him. Pick the phone up.” and there was Chick. This is one of the most funny things he ever said to me. He goes, “I know you're busy recording a lot and you have a lot of stuff going on, but would you consider being in my band?”

I was like, “Can I come over now?” I was so wanting to be in that band. It was hilarious, and just the way he said that it was like, “Are you kidding? Anybody would want to be in your band, who wouldn't want to be in your band?” So that's how it started.

How about you, Eric? John, was that your doing to bring him into the band. Did Eric come in next or was it Frank?

Eric Marienthal: Scott Henderson was first.

John Patitucci: It was Carlos Rios who played on the record and Scott Henderson played on some tracks. Originally Chick wanted Carlos Rios, but he was too busy playing with huge rock bands and making tons of bread with Stevie Nicks and all these people. He wanted to stay home. He didn't want to go on the road with us, so Scott Henderson wound up doing it.

Eric Marienthal: Then Frank came in and after one tour with Frank, apparently Chick wanted to add a horn player. If I'm not mistaken, it was John who recommended that Chick go hear me, is that right, John?

John Patitucci: I think it was me, but it might've been Ron Moss [Chick Corea’s manager]. Ron knew you from Novello, I think.

Eric Marienthal: I was playing with a friend of Chick's, a keyboard player in LA named John Novello. We were playing every Monday night in Hollywood and this is 1986. That year and the year prior, I think the first Elektric band record may have come out, if I'm not mistaken. I got the gig in 1985, b

John Patitucci: No it didn’t come out until 1986.

Eric Marienthal: The next record came out in 1987 but we recorded, I think at the end of 1986 and somewhere in that period, when that record first came out, a mutual friend of John and mine, Mike Labrador, we would sit and listen to that first Elektric Band record and just wear it out, just like thousands and thousands of other people and musicians did. It was the gold standard of music at that time. Even when that original call first came, it was just so very surreal.

I was playing at that club and, I had no clue that Chick was going to come hear us play at this little teeny hole in the wall in North Hollywood. We're playing and there are probably 25 people in the audience, the club could barely hold more than that probably. The door opens and about three or four people walk in and one of them has round-rimmed glasses. I'm flashing and I think, “Wow, I can't really see but it looks just like Chick Corea.” He gets a little closer and I think, “Oh my God, that is Chick Corea”. My wife Leanne was in the audience. It was one of the few times she actually drove all the way up to hear this gig. She saw my face just drop and she looks at me like, “What's wrong, are you okay?”

I talked to him at intermission. On the second set, John invites him to come up and play. Chick comes up and he says, okay, “How about ‘500 Miles High’?” Thank God I knew that tune, because it would have been a bit of a drag if I had said, “Oh gosh, Chick, no, I don't know that, how about if we play a little F blues or something, you know?” He played and he was very complimentary afterwards. The next day - this is in the mid-80si - I was playing in the Disneyland band. As goofy, no pun intended, or as silly as that sounds, it was a five-day-a-week, year-round, full benefits, good paying job with a lot of good musicians. It was a good gig that I didn't want to do for much longer.

Anyway, I was playing there and remember in the mid-80s there were no cell phones or anything. The band phone rings in the break room, just as we were on a break. The bass player answers, looks at me and everybody’s talking, and he says, “Hey Eric, the phone's for you.” As I'm walking up, I ask, “Who is it?” In answer to my question, the bass player says, “Oh, he says it's Chick Corea's manager.” The conversation just got sucked out of the room. So I said, “Hey man, how'd you get this number?”

I was just going to ask that. The phone in the break room at Disneyland?

Eric Marienthal: I've never forgiven my wife. When Ron called my house that morning she said, ”Oh no, Ron, he's not here. Eric works at Disneyland. Here's the number.” Any credibility or mystique I had probably went out the window, but he did call and we had a conversation. He said, “Yeah, Chick really loved the way you played last night and wants to add a saxophone to the Elektric band. They're in the middle of the Light Years record now, and he'd like you to join the record and once the record's done, they start the world tour, starting in South America, I believe, and go from there. What do you think?”

I'm like, “Oh gosh. I don't know, man. What does it pay?” Well, needless to say, it was such a dream gig I would have never even dared to imagine that I'd get called for something like that. Everybody in the band room is hanging onto every word of my side of the conversation. I hang up and I jokingly, but not so much jokingly, frankly, I turn around and I looked at everybody and said, “I quit!”

John Patitucci: That's incredible. “I quit!”

Your Jerry Maguire moment. Did the band gel right away?

John Patitucci: Well, Eric just jumped in there and he could deal with whatever Chick threw at him which was a big thing, because Chick was such a heavyweight composer. He needed somebody who could not just improvise and play good solos, but he needed somebody who could deal with all that stuff. Eric was perfect. Also, Eric was a friend already, so for me, that was amazing when he joined the band because we became like brothers, thick as thieves pretty quick.

Eric Marienthal: Absolutely. If you listen to those Akoustic Band records, to say the group gelled would be the understatement of all time. It was one brain with six hands, it was just ridiculous. Frank fit in so beautifully as well, just on every level. As I said a moment ago, to be a new member of that group, before that first rehearsal, I stayed up many nights, not being able to sleep thinking either “Man, am I going to be able to cut this?” or “Man, I am not going to be able to cut this.”

As the band recorded and went on the road, during rehearsals, that band walked in and we weren’t rehearsing music, we were working on balance and blend and sound, because none of us were going to walk into those rehearsals unprepared in front of Chick Corea. It wasn't even an unspoken rule. It was just out of respect and love that we wanted for Chick to know how much we loved him, how much we appreciated being in that group, and how much respect we had for him and his music. It ended up being a very comfortable, very family feeling—a great, great environment.

John Patitucci: It was a great crazy sight-reading band. Frank wasn't as much a sight reader, but he would memorize all the music. He would just learn it and he would never have to look at anything. But the rest of us were really sight reading.

He would bring in a new thing, line it up and say, “Let's go.” The band learned music remarkably quickly. Some of the times it worked out great because we would be out there playing the music and then go make the record at first. Then it became the opposite. He would bring new music and then we would read it down. We'd rehearse a little bit, just if he was bringing in new music. It seemed like people learn the music fast.

Eric Marienthal: I think for marketing, obviously you're trying to sell records, so you make the records and you go on the road to sell the record. But over the course of 18 months of traveling, if we had recorded the same songs again, after all that touring, the music would have evolved. John and I were joking about the fact that we would follow Chick often after he would solo, and it was time for us to solo. His solos were so unique and inventive and always in the moment. He never relied on any licks, ever.

We always talk as musicians about the ultimate is to be able to play whatever you think. It's like hitting a score of 18 on the golf course. That is, you're never going to hit 18 holes-in-one, but that's the ultimate goal, you know - not that I'm a golfer, but it's an interesting analogy. With Chick, he had that kind of connection with his instrument and when he would play like that, and then it would be our turn to play, we felt compelled to try to be as creative and unique and stretching as we could.

The more we'd stretch, with the way he would comp, it'd be like a nonverbal way of saying, “Yeah, man, yeah, go for it. Love it. Do it, do it, go.” That's why it just felt so comfortable. I think some of our best individual playing happened with Chick because of that musical environment that he created.

John Patitucci: Yeah, the comping was ridiculous. I remember sometimes after playing with him for a while, I would start to play something and we wound up playing unison. He just read my mind. He played exactly what I was playing. There's no way he could have known what I was going to go for and he just played it.

Eric Marienthal: You hear a lot of that on this new record, by the way. I mean, if you really check it out, there's some amazing communication between you and Chick, which is phenomenal.

John Patitucci: I was listening to some of it but the saxophone solos are amazing on that record. We all got sort of brutalized at first by it, because he was so strong that our solos sounded puny. But after you let a decade go by or whatever, and you sort of get used to the traumatization that you first experience. Then you just keep going. It forces you to grow.

Eric Marienthal: Puny would never be a word that I would describe about any of your solos ever.

John Patitucci: I felt like it. I hear a freedom in Eric's playing that that was born out of over 10 years of having that comping come at you. It really changes you because it forces you to leave space and have a dialogue. You can't play with Chick Corea and just try to play straight over him. It won't happen. He's always in there. It's kind of like he and Herbie, like their comping is so compelling that you have to stop and check it out. It makes you phrase, it makes you breathe, because it's so beautiful and so strong. If you ignore it, it's going to sound really dumb.

Both of you went on to be leaders of your own groups after this. What did each of you take from Chick as a band leader, and what sort of lessons did you learn from working with him.

Eric Marienthal: I learned that being a band leader is not to be a band leader, that you're one of a group. It's as if you're sitting around the dinner table and everybody is talking about one particular subject and everybody has an equal contribution to the conversation. At one point, you're talking about this and then the next moment you're talking about that. Being able to listen continually, that was what, as I alluded to a minute ago, our sound checks or rehearsals were always about balance on stage and being able to hear each other. That was 90% of what we would do was to make sure we could all hear each other well. To be able to communicate and make sure that everybody's voices were heard. Everybody's contribution is part of the total conversation.

It was the Chick Corea Elektric Band after all. It was his band, it was his music, but it never felt like he was the strong man in the group. I'm sure with every band he ever put together, he put those people together for a reason because he liked the way those people played. He let everybody play. I don't remember ever hearing from him, “Yeah, you should play more like this or more like that.” There may have been volume issues, such as a speaker being too loud, or was a monitor too loud or something, or not loud enough. It was just to be very inclusive and not to be totally married to a certain thing. Sometimes we’d play things at different tempos and we would say, “Well, we're playing this a little faster. We're playing this a little slower.” And Chick’s response would be like, “Yeah, we are.”

It was what he felt like at the moment. We weren't trying to chase the record or we weren't trying to chase anything that had already been done because we're trying to emulate anything. It was always fresh, it was always new and it was always very open and inviting. Not to be corny, it was also just very loving. It was a very loving group. We all really loved each other a lot and that's born out of respect for each other. That’s what I learned from Chick that as a band leader, you want to make sure you love everybody in your band as people, because if you're on the road, you're on the road for the other 22 and a half hours of the day that you're not on stage for that 90 minutes or whatever. You have to love the way they play, because ultimately you're trying to make good music and you can't do it unless you really have that kind of feeling about each other.

John Patitucci: I think because Chick was with Miles, he learned some valuable lessons there about just what Eric was saying. You hire people who are traveling musically in a similar direction that you want to go in. He was very good at seeing who the young player was in front of them and their potential. He was really good at getting a bead on your core and then helping you enhance that, helping you grow and pushing you also at the same time to be a better version of who you are.

He was uncanny like that and he gave you a lot of space to experiment. I think that's an interesting way of doing it, which is against what some people think of when they think of being a band leader. They think of just telling people what to do all the time and constantly shaping the direction of the music, overly shaping it.

Chick wasn't like that. I felt like I had a remarkable amount of freedom. It’s interesting when I started playing with Wayne, it was the same thing, they were the children of Miles. You were in the band because they trusted you. You were in the band because they knew there was something there that matched where they wanted to go. They didn't choose anybody that wasn't going in that direction. That's how they chose their players. I think it was about directionality and also how they were as a person, if they were fun to be around because with Chick, that's some of the heaviest touring anybody could ever do is playing in his band. It’s not, “We're not going to go out some weekends and I'll see you later.” No. I remember doing two-month tours of Europe, one-nighters and not many days off.

What was it like to come back about 25 years later? Was it like the proverbial analogy of riding a bike?

Eric Marienthal: There was the Elektric Band Two in there for a while as well. So it wasn't like the band existed and then it took a decades long break or anything. There were years where we didn't play, but the band always existed and we were doing a lot of Elektric Band things, periodically. I think, those first years, for those 10 years or so, it was real steady. It was kind of the main focus for Jim and John?

John Patitucci: You were in the Elektric Band Two. I wasn't, and neither was Weckl.

Eric Marienthal: It was Gary Novak, Mike Miller and Jimmy Earl. We just made one record, but we toured quite a lot, actually.

John Patitucci: Did you tour for about two years?

Eric Marienthal: Yes, then the band took a minute and then the original band came back together. We did various things. I guess it was a little bit of a hiatus, but not for very long. I mean, a couple of years or so. Then we'd always come for the 60th birthday, the 65th birthday, 70th birthday, 75th birthday. There were always other shows around those things. We did that record To the Stars I think in 2003, if I’m not mistaken.

John Patitucci: We did some gigs around that too, after that record came out. I remember playing in Canada and some other places.

Eric Marienthal: Then those years, 2016, 2017, 2018 even, when this new live record was recorded, there was a significant amount of touring, around those years too. We were doing quite a bit, quite a lot really throughout the whole 35 years that we were around.

Had the band changed in its sound? It sounded to me very similar, just a little bit more powerful.

John Patitucci: I think everybody grew up a bit and I think people got better. That's the hope, right? I also think we were more relaxed. That's what I noticed. The band had more weight because everybody was more mature. I think we grew up. When I think about that band, I started when I was 25 when I got that gig. I was a pinhead, and I really had a chance to grow enormously just playing with him. I think later on, you're in your forties and then you're in your fifties and, and now I'm going to be 64 in a few days, it's a lot of time passing.

That’s another thing about him. He really wanted it to stay together. What happened was for me, I think I was the first to leave because I was having some issues in my first marriage and I had to leave. Chick was such a road man, he couldn't understand. I was like, “I have to go home to see if I'm going to stay there.” He was disappointed that I was leaving, but I felt like I had to do it. I was in both bands, in all the bands so I needed some time to figure out what the heck was going on because it was a life crisis. I left the Elektric Band and stayed in the trio for a little bit. Then that all worked itself out. After I was remarried, I was in this quartet with Bob Berg and Chick and Gary Novak. Then we started to do more after the Elektric Band Two. We started doing reunion stuff. I made as much of that as I possibly could. There were only a few instances where I couldn't make it, but I did make a lot of it after that, right?

Eric Marienthal: I'm pretty sure you sure did. It's a very good point about the later years. I think early on, because I was in my late twenties when I joined the band as well, you're trying to make your mark, we're getting our first record deals. There's more at stake. You’ve been practicing and practicing, to get gigs like that. Suddenly you've got the gig and you've been working, working, working to try to get a record deal. Then there’s a record deal and now it's time to make those records and see if people are going to buy them and whether you're going to have a career or not,

Decades later, people did buy the records and we did have careers and it was all going very nicely. You hit the nail on the head because at that point we're just all much more relaxed. There wasn't the same kind of pressure that there had been. The drive to make music that was good as possible never changed, but just like with everything, you get a little older, you get a little wiser and, you realize, we're all going to be dead soon. [laughs.]

John Patitucci: Also, you're not as traumatized when you're playing one of those tunes and he just takes off and obliterates the universe in one solo. By then, you're used to that because you've been dealing with it for decades. It's like, “Okay, there he goes again,” as opposed to, “Oh my God. I'm frozen. What am I going to do?” Instead, you think, “There he goes again. He's okay. He just annihilated the universe.” You get used to it. He's never going to play badly. So, just deal with it. He's going to kill. It's going to be amazing. You're going to have to find something. You grow up with it.

Eric Marienthal: Listening to the new live record, Dave Weckl was very involved in the production, in the mixing of the record and on every level.

John Patitucci: He did amazing work.

Eric Marienthal: Yeah, he did amazing work. I don't know about you, John, but I hadn't really heard much of that music.

John Patitucci: No, I didn't until Dave got involved.

Eric Marienthal: When the office sent the final version of the record, I was on a session or something. I was driving home one night and it's two hours of music, right? It's two CDs worth. I'm listening to the MP3, whatever you sent me, and I got home in about 45 minutes. I just sat and listened to the rest of it in my car. I realized, again, not to be corny, but I was crying, listening to that music. It was just emotional that it won't happen like that ever again. It’s emotional to be so insanely thankful to have been in that situation in the first place, and just to listen to the band and that music.

It's pretty rare. You listen to the records, but it's the first live record and actually like a real gig so to listen to what we did, I'm insanely proud of it and it's just awesome. Especially for us in the band, it conjures up a lot of emotion on so many different levels. It’s really good. I think the recordings capture some really nice performances and it reminds us of the contribution that Chick made to our lives.

John Patitucci: I feel like that band was always better live than it was on the records. While the records were strong, that band live, what could happen improvisationally and all the things he would do and we would just peel off in all these directions. We just played together so many hundreds and hundreds of concerts and you can't even distill that down to one recording, so it's nice that there's a live record and it's kind of fitting that it was the last one.

Is it sacrilege or inappropriate to ask, have you considered playing together with another keyboardist?

John Patitucci: Well, we did it at Jazz at Lincoln Center. They called me at one point right after he died because there was no memorial service. They said, “Would you put together this thing?” I lost sleep for about a year trying to put this thing together. People came in, people came out, people got COVID. It was insane. When we did do it, it was beautiful. We did two nights and the Elektric Band was part of that. We had Jeff Keezer play. Originally Frank could do it but then it got moved because people got COVID and it got annihilated. Adam Rogers played guitar in the band and Keezer and Eric and Dave and I, and it was fun. Obviously, there's nobody like Chick Corea. There never will be another Chick Corea. But we've talked about it and we're toying with the idea of doing things here and there. There are keyboard players that so love and revere Chick. Keezer is one of them and he has mad chops.

Billy Childs, too, right?

John Patitucci: Well, he was very close with Chick. He was at many of our recordings and rehearsals. Chick really loved Billy and he really respected Billy's compositional thing too. Not just his piano playing, because Billy is a classical music composer as well.

Eric Marienthal: As far as the tribute to Chick at Jazz at Lincoln Center, John put that whole thing together. It was a massive undertaking. If everything had gone according to schedule without interruptions and having to reschedule and things, it would have still been just as crazy an undertaking. But with all the curveballs that were thrown at poor John, not only beforehand but during. It was quite the herculean effort. There were over 40 musicians altogether, right John? Herbie, Hubert Laws. I mean the list goes on.

John Patitucci: Something like that The drummers were Gadd, Weckl, Antonio Sanchez, and Brian Blade. Not too shabby. I was trying to get Roy Haynes and Lenny White and some other people too, but it just didn't work due to people's schedules. Then the COVID thing. I wanted to get DeJohnette but we literally couldn't in just two nights of music. The one night was three hours long, but I have to say it felt right.

Eric Marienthal: Actually the first night it was over four, but you had a lot of people who were speaking, myself included. I don't think anybody spoke terribly long, but the second night, I don't know if it was your suggestion but there was less speaking.

John Patitucci: No, no, it was somebody else from above.

Eric Marienthal: You spoke as you should, Herbie spoke, maybe Hubert Laws may have spoken that second night too, but it was whittled down. Nobody complained about having it be too long.

John Patitucci: It was the only memorial service for Chick. Like at a memorial service, people really shared their heart. People played their butts off. It was pretty unbelievable the way they played. I was playing some stuff, but McBride played and Carlos Henriquez played.

Eric Marienthal: People were playing a lot of Chick's music, like Herbie and John played “Eternal Child,” one of the great songs. Herbie just played it as it had never been played before, but still did honor to the music. It was incredible. You could have heard a pin drop in the audience. It was ridiculous.

John Patitucci: He did his thing. We grew up listening to Herbie and then got to play with him. I've played with him a fair amount and when you grow up, it's all magic and you don't even understand anything that's happening. Then you learn a lot about what happened by playing with him and Wayne and Chick. Then he comes out there and you play that song and you feel like a 13-year-old kid again. He’s going to the moon. You're playing with him but at the same time, you're going, “How in the world did we get here?” Kirby's taking us to Mars and now we're going to go to Jupiter and he always gets back on time. It's like, okay, sometimes you're with him and you're going out there and you're thinking, okay, I'm holding the form, I think this time he's not coming back and bam, there he is. You're like, “Okay, it’s unbelievable.” I know Chick revered Herbie. If there's one person that was another pianist that he was close to, there are certain people. Herbie was the only one that he really did duets with, right? But he also totally loved McCoy Tyner. He was a huge McCoy fanatic and you can hear it in his playing, but Bud Powell, he also said Horace Silver was a really early influence too. Bud Powell, Wynton Kelly also too, and Monk was huge. But in terms of a personal relationship, it was Herbie.

Eric Marienthal: Remember at Chick's mom’s memorial, they had two pianos set up at the memorial and Herbie and Chick played an improvised duet. The pianos were set, crook to crook, so they could see each other. That was probably one of the most musical, amazing things I've ever seen in my life. Chick Corea and Herbie. It was here in LA. Watching the two of them improvise and knowing they were such close friends at Chick's mom's memorial.

John Patitucci: I remember that. That was really ridiculous.

Eric Marienthal: It was one of the most mind blowing musical experiences of my life. I can't imagine I've ever seen anything more beautiful.

John Patitucci: I got to do one other thing. We did a thing in Hungary where Chick Corea had written this beautiful piano concerto that was just a trio piano concerto. He was working on it on the road. They were playing bits and pieces of it, but he didn't ever get a premiere. Brian Blade and Christian McBride had been working on it with him. So then when we did the live trio record towards the end of his life with Dave [Weckl], he was saying, “I want to do a recording of it with you and Dave and do a performance.” And he didn't make it to that.

We did this big concert at the Mupa, which is a giant concert hall in Budapest, Hungary. Beka [Gochiashvili], the young pianist from Soviet Georgia, Gadi Lehavi from Israel, and Daniel Szabo from Hungary each took a movement of the concerto. Dave and I were there. That was also videoed.

Those two events were the only things I know of where it was a stated memorial thing for Chick. There was never anything else that I've seen. And I think there was one thing for him that some pianists put together with Gayle at Carnegie Hall after he died.

I don't mean to diminish what happened at Carnegie Hall either. I'm sure it was amazing. It was only piano players. And I think Ron played a little bit too on bass so I'm sure it was magic too. I just didn't get to see it. But as far as I know, those are the three things that I know of. Usually there's a big memorial service. There's a big tribute thing and all these things.

That's a whole other topic, how this happens with musicians where sometimes they don't share what’s going on with themselves health wise.

John Patitucci: It's a very tough thing. I understand why of course. We have to be sensitive to the family first. But there's like millions of people in the world who want to express their love for these people, especially somebody like Chick. With people like this, you can never have enough tribute, because what they gave, you can't pay back.

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.