In the early eighties, if Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers were playing in New York City, I was there. I’d first heard the band live in the summer of 1981 when trumpeter Wynton Marsalis and his brother Branford had recently become Jazz Messengers. And I was there when another young lion and son of New Orleans, replaced Wynton, Terence Blanchard. Since then, he has gone on to lead his own band, compose more than 40 film scores and earn six Grammy awards. It has been an amazing journey to personally witness. I cried tears of sheer joy when Terence become the first African American composer in the history of the storied Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. Last season, his opera, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, caused a sensation at the Met, setting the stage for one of the most notable premieres in recent memory.

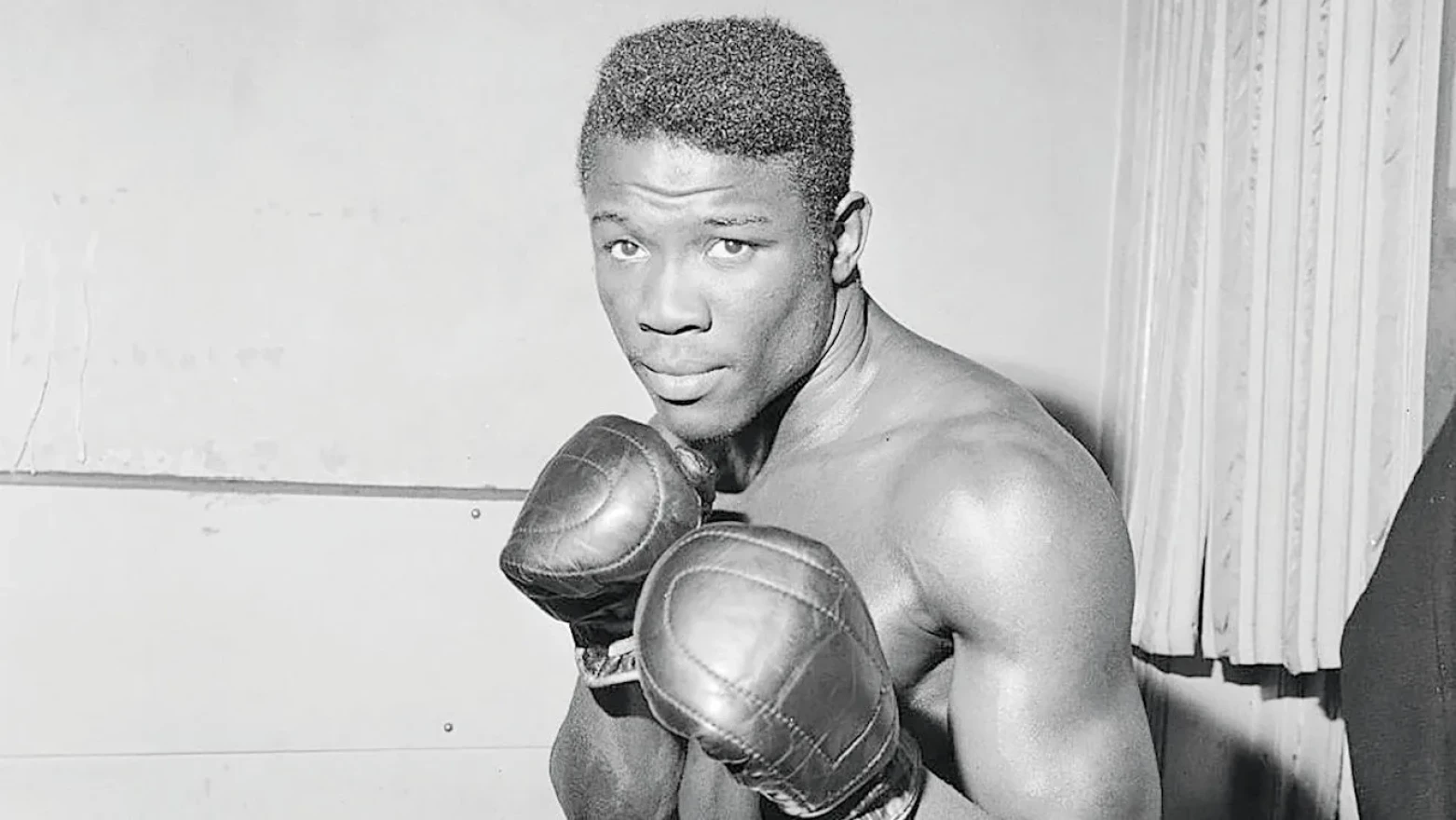

Now, Terence is back with Champion based on the story of legendary boxer Emile Griffith and directed by James Robinson, starring bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green as Griffith. Yannick Nézet-Séguin is the conductor. He talked with me about the unique challenges and rewards of writing an opera.

Watch our conversation here:

Interview transcript:

Lezlie Harrison: It's been a while, but you have been busy, so congratulations and keep on doing what you're doing. Last season, your opera Fire Shut Up in My Bones caused a sensation at the Met, setting the stage for one of the most notable premieres in recent history. Now you're back with Champion based on the story of legendary boxer, Emile Griffith, directed by James Robinson, starring bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green as Emile and Yannick Nézet-Séguin is the conductor. You already made history with Fire Shut up in my Bones. Now you're back with this exciting second opera project. That takes a lot of work. Did you have some downtime to work on it during the pandemic?

Terence Blanchard: You know what's interesting? Champion is actually my first opera. I wrote this one in 2013. Fire Shut Up in my Bones was my second opera. For this production of Champion I had do a lot of revisions. We've added a couple of arias. Since there were a lot of spoken words in the original version, I went back to write musical lines. Some things we totally rewrote, but we added other text and dialogue to it. There's about 30 to 40% of it that's new.

Can you tell us the story behind Champion: Love and Boxing?

While it's the story of Emile Griffith, it's really a story about redemption and forgiveness. Emile was a welterweight fighter from St. Thomas, who was a reluctant fighter. Fighting wasn't his first choice. He loved to sing. He loved to dance. But a guy recognized his physical attributes and started to train him. He rose to the ranks of becoming a welterweight champion. He fought a guy named Benny Paret twice and each one of them won one of the fights so they had a third deciding fight.

Benny tried to get a heads up over Emile emotionally in the press conference. He knew Emile was bisexual and it was something at the time that we didn't talk in public or in sports. So he outed Emile at the press conference by calling him a maricón. Emile was extremely upset about it. The night before the fight, Benny Paret had a dream that he should get out of the fight. He tried to get out. But he couldn’t so he went on with it. Emile caught him in the corner, hit him 17 times in less than seven seconds, and knocked him out. Paret fell into a coma for 10 days and then died.

Emile was devastated because they were actually friends. He struggled with his career after that, wouldn't fight in the corner when he had fights. He wound up becoming a security guard at a correction center. Years later Emile was coming out of a gay bar after he retired and was beat almost to death. People tend to think that that was the start of his dealing with dementia . He said something later on in his life which is the reason why I wanted to write the opera. He said, “I killed the man and the world forgave me. But I love a man and the world wanted to kill me.”

What attracted you to that story particularly?

Listen, when I won my first award, I kissed my wife at the Grammy's and didn't think about it until I thought about Emile becoming welterweight champion and not being able to celebrate that openly with anybody he loved.

That's beautiful. We need more stories like that told, so thank you again. Now an opera seems like a huge undertaking. Can you explain in layman's language how you approach such a large scale project?

Prayer and alcohol and a lot of late nights. I mean, I was scared to death. I had heard a lot of opera growing up because my father loved the opera, but I had never thought about writing opera. It was important for me that my operas all sound natural because when I listen to Puccini, I love how the words tend to dictate what happens melodically.

I was scared and wanted to make sure I did it right. I took the libretto and read it out loud. When I would read it out loud, I would write the rhythms from that. I would put those rhythms underneath the libretto for the entire opera. Then I would go back and create melodic lines and then think about scenes and how the scenes should be dealt musically, and just go from there.

I called my composition teacher, Roger Dickerson, who told me, “Stop thinking, but just tell a story.” That was probably the best advice I could get. Then I literally took the attitude to just go ahead and do this and see what happens. If it doesn't work, I'll just go back to my other life and leave this alone. That's what I was thinking.

Well, look, it has paid off. Can you tell me how different this is from writing a film score or the music that you write for recordings?

Actually, it's similar to writing music for my recordings because when I'm writing music for my recordings, even though the imagery never manifests itself into something concrete, there is imagery that kind of influences what it is that I write for my band. With film, I'm responding to something somebody else shot and cut together. That's not the case here. I'm reading the libretto and I'm imagining all of the scenarios in my mind and then trying to set the tone for those things musically. The beautiful part of it is that when you work with great collaborators that you trust, they bring in these ideas of how to stage it and how to light it, and deal with the sets. All of that really takes it to a whole another level.

We just had a rehearsal, doing a whole run through on stage with some of the guys, not everybody but some of the guys in their wardrobes because we were working on quick changes in between scenes. It looks phenomenal. I'm really trying to figure out how the hell I got here. I’m thinking, “Go with this, run with it, Terence. You’re already goofy a jazz musician, so you may as well run with it.” I'm taking the same approach here. Just continue to work hard and try to learn as much as I can.

You got Black folk going to the opera in droves so keep on doing. With Fire everybody I know was going to the opera. “What are you wearing? Are you going to the opera?” That was the talk of the town, me included.

That was really powerful for me. Those Black people need to know that their presence helped save the Met. The Met was in financial trouble, but Fire Shut Up in My Bones, due to everybody that came, really helped. That's why I'm here this year. This other journalist told me the only other composer that had back-to-back operas at the Met was Richard Strauss in 1945. I owe a debt of gratitude to everybody that showed up and came out and supported the opera.

Well, we were all there and I remember the excitement about it. One, because it was you, and because you're the first African American. How important has your director James Robinson been to this achievement?

Extremely important. There are certain things that he does, that aren’t in the libretto or in the music, that really helped to tell a story. There's one scene in particular where the mother is having struggles talking about what it is that she did. Her son, the young Emile, is a little upset and the older Emile, who's a wiser guy, is standing behind the younger Emile.

This whole opera is about a flashback so we have three Emiles of different ages. Jim Robinson said, “Hey, why don't you just shove the younger Emile and make him go over and give his mom a hug?” Well, that's not in any of the libretto of the music, but it was a powerful move. He does stuff like that all the time throughout the production. It really takes the story to a new place.

Tell us a little bit about the cast.

I'm so lucky to have Ryan Speedo Green. Unfortunately, the way we learned about him was through the death of one of the other principals, Arthur Woodley. He was going to play Uncle Paul in Fire Shut Up in My Bones. We suddenly lost him and then Speedo fell into his place. I heard him in rehearsal and we just thought he was phenomenal. He is an amazing voice with an amazing story. He's come a long way. He was a child of abuse and had a troubled childhood, but now he's one of the leading male vocals in the operatic world. Eric Owens, who plays the older Emile, is a veteran beyond belief. He was one of the male leads in Porgy and Bess.

Here at the Met, Latonia Moore also played the mother in Fire Shut Up in My Bones. She's a soprano that's beyond belief. Brittany Renee is a new talent who's playing the wife and her voice is just amazing. Then we have a homeboy man, Paul Groves, who's actually a tenor who's playing Howie, the trainer of Emile. But I have to tell you, all of these voices, even the voices in the chorus, they're first rate. I told somebody the first time I came here, I said, “It's a weird feeling walking into a room of like 50 people and being the only dude that can't sing.” They want me to illustrate stuff to them and I'm like, “No way. I'll play on the piano.”

So there is a cast of eight?

No, the production is huge. We have about 40 people in the chorus alone. There are about eight to 12 principals. Then we have about 20 some dancers, and actors as well. Plus, an orchestra with a jazz trio of Adam Rogers on guitar, Matt Brewer on bass and Jeff “Tain” Watts playing drums.

What has the advanced response been like so far?

Oh, it's been crazy. This opera Champion is even more dramatic than Fire Shut Up in My Bones, even though it was my first opera. It’s been a while since we've done it, but now doing it here and with the production being bigger than it's ever been, it’s really a crazy thing to experience, especially today. We did a full run through of the entire thing. I feel very blessed to have these experiences with these folks. They not only are the great people to work with, but they're helping me learn and helping inspire me to move forward and learn more about opera.

Listen, you're turning us on to opera as well. I think this will be my third opera ever. I want to thank you for that.

I have to tell you there was a guy when we did Champion in New Orleans, there was an African American gentleman in his mid-70s who came up to me and he said, “Man, if this is opera, I'll come.” Peter Gelb, Yannick and myself have been talking about how it's important to bring these stories to light that relate to people's lives today. The big thing about Fire was that people saw themselves on the stage and it's going to be the same type of experience here with Champion.

I love Puccini. I love La Boheme. I love Turandot, just like anybody else. But those stories were relating to its period in time. It's incumbent upon us…Peter Gelb sees the importance of doing more stories that are current. He's going do Malcolm X and he's commissioning some other composers to write some new stories.

It will make me become a member of the Met. One more thing about the project, that makes Champion special is the fact that a straight male composer is embracing the story of a tortured gay boxer and showing a great deal of compassion for those unique challenges. What is the source of that compassion, aside from basic humanity?

Well, being a kid who grew up learning how to play music in my neighborhood wasn't the most popular thing, even though I grew up in New Orleans. Walking to the bus stop with a horn and wearing glasses didn't make me like the cool kid on the block. I understand what isolation can feel like, and for me there's a certain aspect of it that just makes me sick where we just need to love and let live. Nobody's trying to actively campaign to turn somebody into something that they're not. But we need to accept people for who they are.

I just think it's sad when somebody like Emile couldn't share any of these things openly with somebody he loved. The story is really about forgiveness and redemption because at the end, when Benny Paret Jr. tells Emile just from the family, “We need to let you know we don't harbor any ill will.” You can tell he's been holding that pain for 30 years, so he needed to figure out a way to forgive him.

Well, thank you for telling the story and introducing another generation of opera goers around the world. Where is the opera off to next? You have a run in New York City at the Metropolitan starting on April 10 and running periodically through May 13. Does it have another run somewhere else?

It's supposed to go to Chicago. Then we're trying to figure out who else is going to pick it up. We just learned that Fire Shut Up in My Bones is going to the Kennedy Center pretty soon which is exciting.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.