George Benson is a living legend and he’s still going strong. He’s an NEA Jazz Master and a 10-time Grammy winner who is in the seventh decade of his recording career, which started when he was only nine years old, as "Little Georgie" Benson. The popular guitarist and singer is preparing for his only concert performance in the Northeast this Spring and Summer. He headlines at NJPAC in Newark on June 2, and we are excited to welcome him back to a city in which he has been performing since playing with Jimmy Smith and others back in the day. George and I caught up with what he’s been up to lately, but he also talked with me about his early years learning to play the guitar and jazz.

Listen to our conversation above.

Interview transcript:

Pat Prescott: George, it’s so good to see you.

George Benson: You too. I'm so glad you're still associated with us. You carry a very strong voice in jazz music and we appreciate having you around.

I tell you what, being here at WBGO has just meant the world to me. I haven't seen you in a long time. I haven't seen you since COVID. How'd you spend that time away from the rest of the world?

Well, first of all, getting over it, staying out the way of being infected was tough. But we had to live according to the instructions given us and keep the place safe. I stayed in my home. I got a pretty big coverage of land. So I was out of the public's way, which was very nice for us.

That's the best way to deal with it. At an early age, you got used to being in front of people who were amazed by your talent, even as a little kid. What do you remember about those days? Were you even aware that you had something special or was it just all kind of fun for you?

My mother was a person who just loved music. She took me to movies all the time. She loved those highly emotional movies and musicals. I couldn't get those songs out of my head. She was young enough that we almost grew up together. My mother was only 15 years old when I was born, and it was right after her 15th birthday. She loved music and passed that on to me. I got infected by it, and people used to tell me when I was a kid, “You know something, Mr. Benson, you don't know how big you are going to be.” Years later, I said to myself, “How the heck did they know?” They knew something I didn't know.

You used to play the banjo, didn't you?

I tried to play banjo but that was a little too stiff for me and a heavy instrument. But I played ukulele.

Oh, that's what it was. Ukulele.

When I was seven years old, I played in a nightclub called Little Paris, and it was a pretty swinging joint.

How'd you get in the nightclub at that age?

That was tough because the law didn't allow that. We got in a lot of trouble for that. But it was the beginning of my career and people began to know me as Little Georgie Benson, the singer.

When did you fall in love with jazz? Do you remember? Or was that just a gradual thing that happened for you?

My stepfather met my mother when I was seven years old. And he brought his records with him and his guitar. His records were Charlie Christian with Benny Goodman, the King of Swing. I heard those records day in and day out. I knew every note in those records by whoever was playing solos, especially Charlie Christian, the guitar player. He was something of a phenomenon at the time. That's how I got hooked on the jazz guitar. But jazz itself didn't have an amazing impact on me until I heard Charlie Parker. Then I knew what it was I should be doing. He made the saxophone tell stories, and that's what I wanted to do. I wanted people to get a message when they heard me play or sing.

I fell in love with jazz and studied Charlie Parker's music for years. I found by studying his music and playing along or humming along with his solos because I couldn't play along with him. I wasn't there yet. But once I learned to hum all his notes, it made everything I did easier after that. When I started doing that with a song like “This Masquerade” and “On Broadway,” that was like second nature to me. It was like breathing.

You start the song and I'll show you how to finish it. That's what kind of person I was.

When you do that, it's kind of like you become the guitar. It's like you and the guitar are one. The voice and the notes played on those strings happening at the same time is a very magical, very cool thing that you do.

I always tell people, it's the same brain. It's running both instruments. Of course, the great instrument, the voice, is actually the winner of all things because it tells the story, up close and personal and in a language that people understand. But the guitar is a fascinating instrument and so was the alto saxophone when Charlie Parker played it.

I wanted to be like that. For a while I got a chance to be an instrumentalist. When I joined Jack McDuff , I was 19 years old. He took me on the road. I wasn't good enough to be playing with his band then, but he turned me into a guitar player. He cussed me out every night. “When you gonna learn how to play that thing, man? If you don't wanna learn how to play, just put it down and go home.”

I think it was worth the time he invested in you. Do you remember your first paid gig? The first time you got actual money for playing.

Oh yeah. I was on the street corners with my ukulele after my first day of selling newspapers. You had to be at least seven years old in order to be able to sell newspapers. On or around my seventh birthday, I took my ukulele with me because I didn't have time to take it upstairs and leave it at the house. I looked at the clock on the wall downtown and I said, “I gotta go.” At that time, I was serenading some of my girlfriends on the stoops near my house. I took my ukulele and I asked the guy behind the newspaper stand, “Can you hold this for me till I come back? He said, “Yeah.” I came back, I sold one paper. This is in my whole life. Remember, I'm only seven, I'm walking in bars, packed houses, people everywhere and noisy.

I can imagine a little boy talking, “Do you want a paper?” that they didn't even hear me . So I went outside and the guy said, “Hey boy,” he called me across the street. “Give me one of those papers.” So I gave him the one paper and he gave me a quarter, but I couldn't give him change. So he said, “Keep the change, man.” And I said, “What?” That was a 20-cent tip.

You're like, I like this paper job.

I went to the drug store and saw that candy behind the counter and I was bad looking at the candy I was gonna buy. I have to turn the papers in, the four I had. The guy came up to me, “Hey, little boy, can you play that thing?” I struck out into one of those songs, I can't remember, “Bloodshot Eyes” or something like that. A crowd came around, but you can't collect money and play the ukulele and sing at the same time. My cousin happened to be in the place and he took his baseball cap off and went around the audience and collected more money than I ever had in my hand in my life. That was the beginning of my professional career.

What guitar players that you were hearing as you were developing as an artist had the biggest impact on you? Or maybe it wasn't just guitars to influence your playing, as you said. You mentioned Charlie Parker just a moment ago.

That came late. I was 17 years old before I realized who Charlie Parker was and why I should be listening to him. I was listening to organ players who had just come into their own at the time. They had some great ones out there. They would bring along these fabulous guitar players. A lot of them did not have names yet. They grew later to have names. One's name was Thornel Schwartz. He was from Philadelphia and he played with Jimmy Smith, the great organist and he was my favorite. And he would show me things. I knocked on this door at the hotel. I was just a kid, like maybe 13 or 15 years old, and he said, “Who in the world is that at nine o'clock in the morning?” I'm supposed to be in school. I said, “It’s Little Georgie Benson,” because that's what everybody called me. He said, “Georgie who?” He opened the door and he saw me. He wasn't a Jewish man. He was an African American, by the way. I said, “Mr. Thornel Schwartz, you told me I could come by and you would show me something this morning.” He said, “I didn't say nine o'clock in the morning.” Because he just got in at like maybe six.

You didn't know about that part, about the jazz life yet.

I came in and he said, “All right, play something for me.” I had some raggedy guitar and I grabbed the guitar out of the shopping bag I had it in. He said, “Hey, wait a minute, what was that you just played?” I said, “I don't know.” He said, “Play it again.” I played and he said he started laughing. “Now put that finger over here on the left over here, and…” That's how I got started with those guys. Everybody that came to town that had a guitar player and I worried them to death until they taught me something.

You’ve turned around and really done the same thing for some other guitar players who count you as a mentor and an influence. Great players like Russell Malone and Dan Wilson all credit you as a major influence. What does it mean to you to be able to turn around and do for them the same that these other guitarists did who influenced you?

I know why now I was so diligent at trying to get them to show me something. These guys, I saw them in their young days, the names you mentioned, and then I saw what a few years of tutoring could do. They turned out to be giants on the guitar, just master musicians. I wonder what would've happened if nobody stopped to give them advice or give them some direction. Like those great guys who did it for me, like Thornel Schwartz, Eddie McFadden, Kenny Burrell, Wes Montgomery, Grant Green, Tal Farlow, Hank Garland, Chet Atkins.

I worried all those guys to death to show me something. They did, and they were all proud of me, the ones who lived long enough to see my career. They're still my favorite cats today. When I play, I think about them and somehow or another, their character shows up in my playing. I'm actually a conglomerate of all those guys.

You mentioned Jack McDuff a minute ago. I remember seeing you perform at that little joint up in Harlem on St. Nicholas Place where they would do a lot with the organ guitar combos. I remember being there and everybody was really freaked out that George Benson is there. And you were playing. What is it about the organ guitar combo that works so well?

It became a practical thing to do. The organ played its own bassline and that eliminated one musician. That's big time, because you had to pay that one musician. Organists didn't. A lot of guys would play as duos, with just organ and a drummer. But when you had a trio, you had an organ, guitar and drums. That gave the guitar player a platform, and he now had to earn his salt, because he was the saxophone player, so to speak. Another voice in the band, a real voice. That really helped guitar players all around the world.

Jimmy Smith was one of the greatest musicians of our time. When I finally met him at about 15 years old and with his gruff voice, he said, “Who in the heck is Little Georgie Benson?” Somebody said, “Oh, there's Little Georgie over in the corner. Come up here and play something with him.” I got up on the bandstand. I was so excited. I’m playing with Jimmy Smith. He said, “What do you wanna play?” I named the tune I wanted to play and he started playing. He was so masterful. He started giving me ideas when he played. I couldn't wait until he got finished and let me have a couple of bars, which he finally did. Somehow they didn't boo me off the bandstand. I said, “Oh, maybe this is where I belong.” It's been an exciting and incredible road that I got on. I didn't know what I was doing then, but it led to some great places.

And one of those great places was New Jersey, which has been an important part of your life. And even though you have homes in a few different places, and you spent a lot of years in Hawaii and in Arizona where you are now, I guess it must really feel like home whenever you get a chance to perform here in Jersey like you're going to be doing at NJPAC.

One of my second homes is New Jersey. As a matter of fact, at one point they asked me to run for mayor in one town. I said, “Hold on, no, that'll slow me down too much.” I gotta play, that’s what I do. I didn’t like politics. It's just a little too complicated for me. I didn't like being in charge of somebody else's life, so that bothered me.

I said, “Whatever you do, you are my friend. I love you, but don't nominate me for the for mayor, because I will not run.” I love the state though, because they had nice nightclubs in Newark where jazz musicians and especially the organ groups were very welcome and it was fun playing there. People would come to a particular neighborhood and they'd go from club to club.

Then we’d go down to Atlantic City, New Jersey and play in those bigger clubs with some of the superstars of the time. I met Sarah Vaughan's piano player who was there working. Lots of very famous people worked in Atlantic City throughout the years. It was a great place to play.

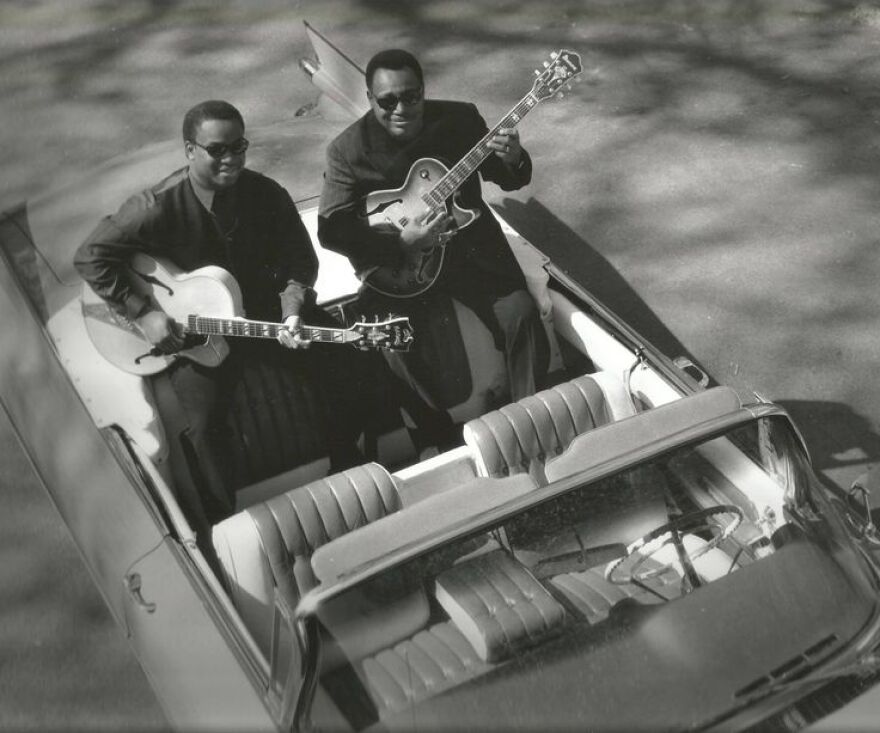

I remember seeing you one time in Jersey at a performance, and you came to the gig in your candy apple red vintage ride. You remember that?

A 1959 Cadillac candy apple red, clean, with a red and white interior.

Do you still have that?

No, I put it up for sale and a guy called me from Montana. He saw it on the internet and he said, “You're lying about that car.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “No car would look that good. A 1959 Cadillac can't look that good. What did you do to it?” I said, “Nothing. That's the way I kept it all these years. I've had it for many years.” He said, “It can't be.” I said, “Why don't you just fly down and take a look at it in person?”

So he did, and when he came to my gate and he saw the car, he was just mummified. He said, “Can I drive it?” I said, “You got that check in your pocket?” He took out the check for real, gave me the check. I gave him the keys, and I sat with him while he drove. He was the happiest guy you’d ever want to see.

Well, you're going to be coming back to Jersey on June 2, even though you won't have the candy apple red vintage ride. Do you remember the first time that you performed at NJPAC, because I know you've been there before.

I can't remember the first time, because I played all over New Jersey. It's a great place for music. One time they were gonna shut down one of the small theaters in New Jersey and they had a town meeting. They were gonna try to convince the government, “Don't do it, don't tear this place down.” So they asked me if I would show up. I said, “Well, I don't know what I could do, but I'll show up because I love this place too.”

So I went there and they actually asked me to come up and speak on it. And I just beg like any normal person would. I said, “Why should people have to go to New York to hear a musician that was born right down the street here? We got some fabulous nightclubs. This is one of the most fabulous playing places for musicians.”

No question.

And you know what? They listened, they didn't tear it down.

That's great. NJPAC has done an amazing job of reshaping the landscape of downtown Newark. I read somewhere that NJPAC has attracted 10 million visitors and more than 1.8 million children since it opened back in 1997. As somebody who has performed there and who also lived in the area, talk about the importance of having first-class world-class venues like NJPAC.

Young people don't know the difference because they haven't seen a lot yet. But when they go into a place they've never been like that, that's been dressed up and specialized for the kind of music that they were desiring to come into New Jersey. They don't know what they were doing to these young people. They gave them a dream, a vision. And each one of them saw their own self in this vision. Years later, when I met these young musicians, I could tell they were going to go a long way because they were dedicated. Their minds had already been made up. They wanted to be on that stage. That's where it began when they first saw what goes on in a music house with the curtains and the stage and the orchestration or the musicians, and sometimes dancers. That’s it. Once you get infected by that, you are hooked for life.

When you come to NJPAC on June 2, I know that with as many hits as you have, it must be really interesting putting together your set list for these shows. What determines how that process goes? I know there are a lot of songs that you don't dare leave out or you'll be in trouble.

That's true. There are some things that I have to play and that's getting more and more as my career goes on. Because we got a lot of hit records now that we didn't have when I first went on the road. I used to play it by ear. I would get the feel of the place. I'd walk in after we had already had a rehearsal early in the day. We had a lot of things we wanted to play, but we wanted to be effective. We came there for them, not for ourselves. We knew what we could do, but we wanted to be effective so they would remember us. I'd go out and once I felt that audience and could see their faces, I automatically knew what to play because they were me. That's me looking back at myself.

You were ready for whatever it was that they wanted.

That's right. If they were all about some tune, I already knew they wanted it, so I said, “Oh yeah, let's not forget ‘This Masquerade.’”

I know your family has always been a big part of your life. What's happening these days with your kids and how's Johnnie doing?

My wife Johnnie has been with me for over 50 years. I met her in my hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I told her, “We're going to New York.” She said, “What do I do about my job?” I said, “You quit your job.” She said, “Quit my job?” I said, “Yeah, I’m going to make you rich.” We almost made it to New York. We got about 30 miles out when I ran out of gas and money. I went to a gas station and I begged the guy to give me $5 worth of gas and. I went back six or eight months later and tried to pay him, but he wouldn't take the money. He said, “I don't remember doing that.” I said, “Well, some people are more giving than others. You must be one of them. Thank you anyway.” And I took back off to New York 30 miles away. My career has been full of that kind of thing, so I can't say that my career is not owed to a lot of people and a lot of circumstances.

Your band is like a family too. The artists who play with you have a tendency to stay a very long time with Mr. Benson. I think that's part of what creates that magic that you were talking about. That gives you the freedom to be able to go to a venue, stand on the stage and judge the audience, and then know that your band can follow along with whatever you're calling out, right?

That's right. I’ll never forget, I met a kid who was 15 years old in Buffalo, New York. He came to Jimmy Smith's sound check at a place he was gonna play that evening. This kid is looking over Jimmy Smith's shoulder at 15, and everything he saw Jimmy do, he reached over his shoulder and played the same identical thing. And he was only 15. I said, “Man, this, this kid is going to be a monster.

A couple of years later, I met his folks and his mother begged me, “Mr. Benson, please don't take my son on the road until he graduates from school.” I said, “Well, that's a reasonable request.” So I didn't. He finally turned 17. He gave his mother the diploma and he took off that night. I finally met up with him in New York. Today, in my estimation, he's the greatest keyboardist alive. Incredible. Ronnie Foster.

All the guys in my band were guys I met off the cuff like that. Jorge Dato, who was the pianist on “This Masquerade” and “On Broadway” and songs like that, came from Argentina. He wanted to play jazz, so he went from Argentina to Chicago, where he met his beautiful wife, a Mexican girl. They had two children. First, he wasn't going to have any children. They saw mine and and he would pick up my boys all the time. I said, “Hey man, where's yours at?” He said, “Me and my wife are not gonna have any kids. I said, “You gotta be kidding me, man.” So he finally did have a couple of kids and I helped them name them. They're wonderful guys today. And one of them is a great musician. But Jorge Delto was one of the finest piano players to play in my band. Once they came with the band, they were solid musicians. If I breathe, they knew what to put with that that will make it sound better.

Are you hearing anything recently that you really like? Who's catching your ear these days? Any new artists that are up and coming that you really like?

You can't count them today. There's so many coming up, but some of them that I heard, and it seems like just months ago, they're already at the top of the class now. Christian McBride, the great bass player. He was only 15 years old a minute ago. Now he is the number one bass player in the world. A fabulous musician

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.