In the history of jazz, there are few artists who loom larger than Sonny Rollins. Influenced by Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker, the 92-year-old tenor saxophonist established a standard for improvisation and performance over the course of more than seven decades. The tenor titan is the subject of a new biography by Aidan Levy, who conducted many hours of research and interviews and produced what might be the most impressive jazz biography since Robin D.G. Kelley’s remarkable book, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original, about one of Rollins’ former colleagues. Levy spoke with WBGO’s Lee Mergner about his long journey in researching and writing the book, as well as what he learned about Rollins that might surprise all of us.

*****

Lee Mergner: How did you come to pick Sonny as a subject?

Aidan Levy: I’ve always been a huge fan of Sonny and I’m a saxophone player to start although I play baritone mostly now … I started on alto, moved up to tenor and then they put me on the big horn when I was maybe a sophomore in high school. Anyway, the first jazz album I ever bought with my own money was Saxophone Colossus so I just listened to that over and over again and gradually got into the rest of his catalogue.

Fast forward a couple of decades and I had the opportunity to interview Sonny for Blue Note Records. I was doing some editorial content for them and it was just kind of a life-changing conversation, to be able to just speak to him for about an hour. I thought, “How many people have I met that had that kind of effect?” Well, nobody, really.

I started looking deeper into his life, his music, his career and read a couple of books that were out there. I really enjoyed those books, but I thought, there’s no comprehensive biography out there that I was hoping to read. I was honestly surprised that I ended up doing this but I had the idea that maybe I’d try to do this myself. One thing led to another and now we have this book. I started out seven years ago now.

I interviewed David Yaffe, who wrote the great Joni Mitchell biography, and he said that when he was starting that project, he spoke with Gary Giddins who asked him, “What kind of biography is it going to be—a one-year biography, a three-year biography or a seven-year biography?” David said, “No I want to do the seven-year one.” Giddins told him, “That’s what it’s going to take if you want to do the definitive biography…it’s not going to be one year or two years, it’s going to take a lot of time.”

I agree. Gary played a pivotal role with this book. It started with a fellowship at the Leon Levy Center for Biography at the City University of New York, which Gary was the director of at the time. Gary, a masterful biographer, decided to support this project and I got to spend a year there, talking with him and doing interviews and beginning my research process. That’s how this book began.

Sonny is a very private guy. He could have just as well said “no” to this. Did he give you his blessing?

Yes. Before I started the process, I reached out to Terri Hinte, his longtime publicist. I just wanted to make sure that Sonny and Terri would be okay with my taking this project. And to my surprise, they gave it the green light. That’s how it began. I don’t know if they realized it would be a seven-year odyssey.

What were some of the more important sources of material for you in terms of research?

First and foremost, Sonny himself. Just being able to speak with him. Over a series of conversations—some of them I would write him a letter and the answers would be faxed. Or questions would be faxed to him and he would write back.

Being able to talk about the story with Sonny and make sure I got the facts straight was crucial to the book. Beyond that I would say the first major source for this book would be Sonny’s own archive that is housed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. It’s only a couple of blocks from where Sonny was born. To anybody who hasn’t been over there to look at the collections or see the library or attend an event there, please go. It’s just an amazing place and an amazing resource for researchers in the community, people who care about Black culture.

The Sonny Rollins collection was something I was really excited about. It had not been processed when I began this book. I had heard different things. Some people said, “Oh, it’s not that much stuff. And others said, “It’s substantial.”

I was blown away by the mountains of material that Sonny had kept and accumulated over the year, because not everybody keeps all their stuff. But Sonny fortunately did. Also, his late wife Lucille clearly kept a lot of that material. We have his writings, as well as his practice material which is voluminous. We have his business records, his programs, posters, and loads of correspondence.

That turned out to be a project in itself, just to go through that entire archive, which has probably more than 100,000 documents in it, depending on what we’re calling a document. Before the pandemic, I was able to get into the archive. I must have been the first person to look into the collection as a researcher. I spent months, every single day, just going through it. I was like living at the Schomburg. And fortunately, I lived just fifteen minutes away at the time.

I went through everything. Like all archives, a lot of it maintains the original order. Some of it is better organized than others. A bit of detective work was involved. I was parsing what was happening, like a journal entry. I would find connections here and there. That was just months going through that and kind of living in that archive, just figuring out what’s really going on with Sonny Rollins at different stages in his career. That was the major source for the book. That’s something I was really excited about. Something that made me want to do this project was having an archive like this. I’ve seen very few examples of jazz archives that have this breadth and scope.

Historians call that a primary source. There’s nothing better than that.

Exactly. Oral histories would be considered another kind of primary source. But to have the documents that came into being at the time is also invaluable to this project. And there really aren’t many jazz archives like this.

Max Roach would be another example of that. I did a lot of research in the Max Roach Collection in the Library of Congress. That’s another collection that’s just staggering in its scope and would take months to go through it.

I spent a lot of time there because of Sonny’s relationship with Max. That was another very important archive to this project. I would say that basically the book came out of archives, interviews, and the recording archive. The other archive that I would name that is key to this book, and I don’t think I could do it without it, is the Carl Smith collection. Carl Smith is an independent archivist living in Maine who also is the founder of a high-end audio company called, Transparent Audio. Carl has spent decades now amassing what I think is the greatest collection of live recordings of Sonny Rollins in the world.

Is he the one who recorded the 9/11 shows in Boston, later released as Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert?

Exactly. He recorded the 9/11 concerts surreptitiously that were eventually released. Thank God it was, because it’s an unbelievable recording and it won a Grammy. It was a major discovery in the jazz community and people became aware of the Carl Smith collection. I had the opportunity to go out and spend a weekend with Carl in his home audio room just listening to some of this material on the best speakers known to man.

I’m still blown away by that experience. Carl generously allowed me to use the collection for the duration of this project. It has thousands of hours of live tapes of Sonny, going back to 1950. That is the final piece of research that went into this book.

Any good biography has new revelations or surprises about its subject. What was the most surprising to you, as you did the research about his past and his life?

There are so many things really but there was just one story that comes to mind that I found surprising and that drew out the pathos of his story to me. It was 1958 and Sonny had just recently released his album Freedom Suite, the first Civil Rights-themed album of the hard bop era. It was a major work that should have had wider critical attention but did not at a time when there was significant resistance to the Civil Rights movement.

At this time Sonny was going on what was really his first major national tour. He was the only Black bandleader on that tour. It was called “Jazz for Moderns” and it was like a Norman Granz production with Maynard Ferguson and Dave Brubeck. Sonny was performing at Carnegie Hall in November 1958 and he found out right before he went on stage that his mother had collapsed and died.

Here's Sonny Rollins deciding what’s he going to do: Go onto the stage at Carnegie Hall and just play through the grief or not. He decides the show must go on and he gets on stage and he does the concert. And it’s a brilliant concert—according to every critic that was there.

He was really close to his mother. That’s something that came out through the research. But after this night, playing at Carnegie Hall, after late night show he has to make a decision if he’s going to stay in town, make all the funeral arrangements or get on the tour bus at 5 a.m. the next morning at Columbus Circle and head down South for his performance debut there.

He decides that he has to get on that bus. The way I think about it is that maybe that’s what his mom would have wanted him to do, but he makes that decision. He gets on the bus and they go into the South and they play at Virginia Tech and also the University of Virginia. At one of the shows there he encounters some jazz fans who are big Sonny Rollins fans but not fans of the Civil Rights movement. His mother has just died and he has to face down the beast of discrimination.

There’s also the fact that there can be such a thing. That someone can be a Sonny Rollins fan but not a fan of Civil Rights. It’s one of the tensions that goes throughout the book. It’s something that speaks to one of the deep and abiding themes in his life. How can you be a social justice activist through music and what does that mean? How can you reach people who may not be easily reachable? How can you open their ears up? That was just a surprising series of events that came out of the research for this book.

For me, one surprising reveal was just how he and his family struggled economically. I knew that he grew up in Sugar Hill, but they had to move a lot and then when he went on his own as a musician, he also really struggled. There were points where he was literally homeless—living in cars, living wherever he could.

They called it carrying the stick, like a hobo.

Another thing that many people don’t know is his problems with the law, that he had drug problems and was arrested for offenses related to that and did serve time at Rikers. This was no some small thing.

I think there’s a tendency with a lot of our legends to deify them and to downplay some of the struggles they went through, especially with someone like Sonny Rollins. He’s just such a legend at this point. We don’t really imagine him at a time when he’s not THE Sonny Rollins. But of course, he was THE Sonny Rollins for a long time.

But there was a significant period of struggle for him. Years on the road making very little money. Living out of suitcases. His trouble with the criminal justice system really was having to face down such a bigoted system of justice. I spent a lot of time documenting what happened there with the parole system in New York.

It took a long time for him to get to the point where he’s just a revered cultural figure. There was a long time when Sonny Rollins was more of a pariah. I think it’s easy to forget that. I don’t want to exaggerate that part of the story, but the point is that he went through this struggle. This was a part of it. He had to work really hard and he worked harder than just about anybody. There were the hardships that his family faced. Some things that happened were just horrible.

Harlem loomed really large in his life. After all, he lived through much of the Harlem Renaissance as a young person. Great literary arts and cultural figures were part of the neighborhood. I know this meant a lot to him to call Harlem home at that time.

Absolutely. When his family moved up to Sugar Hill and they were living at 377 Edgecombe, W.E.B. Dubois was living at 409 Edgecombe. And that was where so many people lived like a lot of the leadership of the NAACP, like Walter White, and many other people. It’s a beautiful building. It’s still there. You can go and visit it.

Sonny and his friends used to play stickball outside that building at 409 Edgecombe and he was the captain of the team: The Aces of Edgecombe Avenue. Apparently, he achieved some memorable feats at stickball. But probably many times, he would see W.E.B. DuBois coming home from work and he said that DuBois would kind of glare at them, but he would also give them an acknowledgement of what they were doing, because he knew they had the best wall for various games outside there.

Joe Louis would come around. All these political and cultural figures would be right there where Sonny was living. He grew up around that.

Another thing you were able to put in perspective was his famous tendency to retreat and go on hiatus in order to enter into a period of isolation and reflection. It didn’t just happen once, it happened multiple times. Of course, the famous example that everyone talks about is him going up on the Williamsburg Bridge. It turns out that this iconic story about him practicing on the bridge was a bit more than him going up there simply to get away to practice a little. He spent a ton of time there. And he took other people up there too.

He’d be up there up to 15-16 hours a day. Kind of like the postal worker, through rain, sleet, and snow. His decision to go on the bridge I think is really one of the most inspiring aspects of this story. That somebody at the top of their game and after everything he’d been through finally got to that point, at a time when he’s a marquee artist on the jazz scene and he’s playing festivals finally.

Nonetheless, he’s working at such a frenetic pace that he makes the decision to step away. This is at a time perhaps when it’s easier to disappear than it is in our digital era. He just vanishes, more or less. People have no idea where Sonny Rollins is anymore. His phone is disconnected. And he has found the ideal woodshed to work on himself and better himself to get to where he wants to be…where he feels confident in what he’s doing. He just starts going up on the bridge. Every day. Every night. Oftentimes, he’s there for a lot of the night.

There’s a famous picture of Sonny on the bridge, but from your descriptions in the book it doesn’t seem like that was the place where he practiced. Didn’t he have to walk up to another higher part of the bridge, way above the cars?

That’s right. He would play in a place where you couldn’t see him. Passersby who might be walking across the bridge to get to work or whatever might hear the sound of the sax, but they wouldn’t see anybody. They would just be hearing this disembodied saxophone wailing. Of course, this goes on to inspire the character of Bleeding Guns Murphy on The Simpsons.

But he’s up there and it’s really the perfect practice space. One thing I tried to bring out in the chapter is the idea that this wasn’t an obvious location to practice. This is not a desirable place to be at the time. It’s full of potholes. There are all these stories in the newspaper about crimes being committed on the bridge or near the bridge. This is the Williamsburg bridge. It’s not the Brooklyn bridge as many people thought. Although I happen to think it’s a gorgeous bridge, this is not the better-known Brooklyn Bridge.

It happens to be around the block from where he was living at the time at 400 Grand Street, so he could walk up there. The other thing is that where he’s practicing is really far out there. It’s a long walk and to be lugging a saxophone up there is a workout in and of itself. Where he practiced on the bridge with some of the metal work also afforded him a workout space. He would do pull-ups and chin-ups there.

Boy, he was really into exercising. He got into yoga later, but I learned from your book that for a time he would carry around barbells.

He would have his saxophone in one hand and a suitcase of barbells in the other as a counterbalance. He became like a bodybuilder at this time as well. Healthy mind, healthy body, healthy spirit at that time.

Another fascinating thing that I found was that a lot of his journal entries from his time on the bridge were preserved in the archives. You could read about what he’s really going through. Fortunately, I was able to put quite a lot of that material in the book. You can read his letters back and forth about how it’s almost time for him to come down from the bridge and return to the stage. There’s material on what he’s reading at the time in order to think through some of the ideas that he's puzzling over at this time, and really come to terms with himself and what his mission is in this life.

I think it’s a fascinating period and we could talk endlessly about it. There’s the campaign to rename that bridge the Sonny Rollins Williamsburg Bridge that was started by Jeff Caltabiano as the Sonny Rollins Bridge Project and I’m a supporter of that. That comes out of that legendary period that he was up there.

People perceived, mostly because of the record Tenor Madness with John Coltrane that these two tenor titans were rivals. But, in reality, there was so much love between them and although there was a little competition, your book pointed out just how deep their appreciation of each other ran.

Yes, they loved each other. They were like brothers, so it was a lot more than that one session and a lot more than the perceived rivalry. Did they have a friendly rivalry? Yes, they did. But it was friendly. The idea was that they were pushing each other forward. Both in spiritual pursuits but also in the music.

Sonny and Coltrane would visit each other, they talked on the phone all the time, they were close, really close. One piece of recorded history that will bring that out is songs that they wrote. You have “John S,” Sonny’s composition which a lot of people think is dedicated to John S. Wilson, the jazz critic, but it’s actually meant to be John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins—John and Sonny.

You have Coltrane’s composition, “Like Sonny,” which comes out of a Kenny Dorham record that Sonny plays on. There’s this one like two-bar passage that Sonny plays in his improvisation and Coltrane took and it became the melody for “Like Sonny.” I don’t think Sonny has any particular memory of playing that line but we would all recognize it instantly if we heard it. Yes, they were close musically, although they are quite different players. They really were working through some of the same ideas, just finding a different way to the mountaintop. They really couldn’t be closer. I’m hoping that what comes out in this book will put that idea to rest that they were bitter rivals. Or that the reason Sonny went on top of the bridge was because of Coltrane.

In part, Sonny was inspired by Coltrane to work even harder on his craft, on his artistry. But it’s not like he was scared off him or something along those lines. It really came out of a closeness and out of mutual respect.

Another thing that comes out in the book and was true of both of those great saxophonists was the utter commitment and dedication to the music. What they put into becoming great musicians. It wasn’t an accident that they became great musicians given their dedication. They both put in hours, all the way through, from the very beginning.

Yes, there was this one period when Freddie Hubbard was practicing with both of them and he would go up to Coltrane’s house on 103rd Street I think, and he’d play with Coltrane and then he’d go down to Sonny’s and they would each, according to Freddie, ask him: “So, what’s Sonny playing?” or “What’s John working on?” There was that connection as well.

In terms of what Sonny was practicing, I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing when I went into the archive. There’s this idea that Sonny has perpetuated, that he’s a primitive. That you can’t think and play at the same time. I do think that when he was on stage improvising that he was in kind of a flow state. However, the idea that he’s just pulling this stuff out of the air from nowhere, that there wasn’t so much work that went into that ability to get on stage and be in an ideal flow state—really just channeling the unconscious. That’s a preposterous idea.

He really worked every single day and was systematic about it. The same way he had become like a body builder, he was doing that on the horn. And he documented it too. There were these exercises that he would do on harmonic relationships, intervals and working through modes and scales—working on the fundamentals every day. He would document this on manuscript paper. You can see this. It’s thousands of pages of material every day that he’s going through.

If anybody thought that Sonny was not systematic in his practice regimen, they’ll see that he absolutely was.

Another amazing thing that I learned was the dental problems he had throughout his career, especially as he became really successful, doing the festivals and big theaters. He really struggled with dental problems, which for a saxophone player is not everything but is pretty darn important. Overcoming that was a big challenge for him.

Yes, that’s your embouchure, that’s your sound. It’s more than just your teeth but your teeth play a big role in getting that sound and defining that sound. You can kind of hear his sound change a little bit in the late ‘60’s and I think that this is part of it. But to deal with dental problems can sideline you as a player and that certainly happened to him periodically throughout his career.

He wasn’t alone having dental problems. Phil Woods recommended his longtime dentist, and I interviewed one of his dentists for the book who was a player himself: Dr. Philip Terman. He took care of so many jazz musicians. Prior to that Sonny went to this dentist, Stanley Nelson, who was a force in the dental community and really a pioneer of dental implants and other kinds of prosthetics. Stanley Nelson was also a big jazz fan. Interestingly, his son is the documentary filmmaker Stanley Nelson, who did the recent Miles Davis documentary.

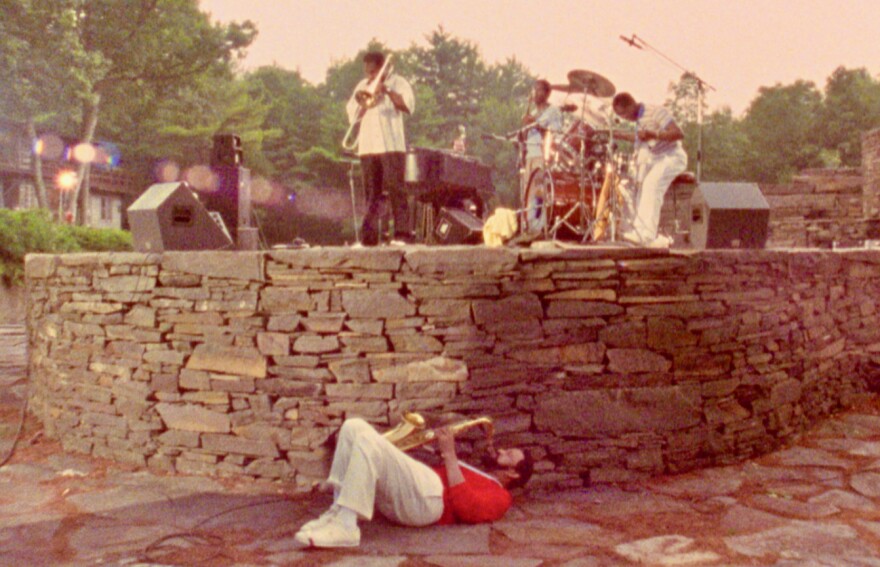

Speaking of documentaries, you talk about Robert Mugge’s great film of the same name, Saxophone Colossus that included footage of a performance at Opus 40 in Saugerties, N.Y. At one point during that concert, Sonny steps off the stage which was a high sculpted rock structure and he basically fell onto the concrete several feet below. The band doesn’t even know where he went and they’re not sure what’s happening, but Sonny is lying there, still playing and it turned out he’s playing through a broken heel.

First of all, what an amazing documentary by Robert Mugge. It really captures Sonny at that time and his process and everything he’s working on—what it meant to be a jazz musician in that era but also just in general. What a moment to capture. No one could have predicted it, least of all Sonny. But part of what he did [as a live performer] was to go into the audience. In this case, he takes a bad fall but he’s Sonny Rollins so the show must go on. He quotes “The Man on the Flying Trapeze,” while playing on his back. And the fans don’t even know that he’s injured like he is. Then the show’s over and he needs someone from the production crew to help escort him. What Sonny said to me about it is, “Don’t jump next time, I might regret it.”

Another point the book makes is that Sonny was one of those artists, who—after struggling and getting paid very little for sessions and basically getting screwed by the business side—advocated not only for himself but for other musicians. He’d tell his peers, “Take care of your business.” That later became an important issue for him and Lucille, who really helped him do that. Were you surprised by his focus on an entrepreneurial mindset and self-reliance?

I didn’t know the extent to which he exemplified that quality. But the idea of artistic self-determination and self-realization was central to who Sonny Rollins is as a person and as an artist. Being able to see in minor detail all the decisions that he made to look out for himself and make sure he’s not being exploited was really extraordinary and a model for other artists and, as you said, he helped out so many people.

For instance, he made sure his publishing was under his own entity to the greatest extent possible. Eventually he started his own record label; his own production company to produce concerts. The idea was really to oversee all aspects of the business and his wife Lucille, after she took over as his manager, really ensured that that was the case. They were just a powerhouse team in terms of making sure that he got a fair deal.

That’s how I got to know Sonny because in the ‘90s I dealt with her with various issues concerning covering him in JazzTimes. I would hear complaints about her because of course she had to say no. However, I found her to always be responsive and if it was a no, it was a no. For my part, she was very good to deal with. You just knew in dealing with her that she was doing the right thing by him.

That really came out. That she was firm but respectful. That she always responded. It was shocking to read her pile of no’s. She kept documentation of everything. In that archive, there’s just a pile of queries and invitations—“The NO Pile.” But also dollar amounts and what the offer was. The number of times she would turn things down was kind of staggering but the point is that she would always respond, whether a yes or a no, with a respectful response. One of the keys to that was to look out for Sonny and make sure that his health was protected as well—his mental health, his physical health and that he wasn’t running himself ragged. At some point it was the end for any gigs. It didn’t matter what the dollar amount was. That was another lesson that came out of the book. If you want to have longevity in the music business, then you need to know when to say no.

One of things that he said “no” to but that she and others pushed him towards was his cameo on the Rolling Stones record Tattoo You, which was mostly a pick-up of various previously recorded cuts. Yet it ended up being a very big record for them. At the time I remember all of us jazz people going, “Wait, why didn’t they credit Sonny?” You brought out, as I discovered when I talked to him for a piece a few years back, that that was his choice. He didn’t want to be known as playing with a rock band, although anyone who knew about Sonny Rollins knew when hearing that little calypso thing on “Waiting on a Friend” that that was Sonny.

I think he thought it would just fly under the radar and people wouldn’t realize it. The one day he’s in a market upstate and hears this song and thinks, “Oh, that actually sounds interesting…wait a minute, that’s me.” But yes, any jazz fan would recognize it as his sound. I think it’s just an amazing moment.

I know that Sonny, in some ways, seems to regret playing with the Stones. He didn’t want to be credited, as you said. One detail that comes out and this goes into that category of artistic self-determination and making sure that he’s doing what he wants to do and realizing his own vision. After that record came out, the Stones were desperate to get Sonny on the tour and they offered him an enormous amount of money – like seven figures – and he said no. He wouldn’t do it. He said, “No, I want to keep working with my own band, doing my own music” and that’s what he did.

One of the amazing things that was consistent all through his life was his aversion to recording, tied into his being a perfectionist, always exploring, never being happy. He was someone who really struggled in the recording studio because of that mindset.

That perfectionist tendency, the idea that you could perfect it, I think just plagued him. He couldn’t go into the booth, he couldn’t listen to playback. There’s this idea that he would never hear playback of his own stuff and it turns out for the most part that isn’t accurate. I don’t think he listened over and over again to it but you can also find notes of him going through various reels and commenting on which takes are good.

When they say Sonny Rollins is his own worst critic, I can say that one of the things he wrote in note form was just unbelievable. I think at the same time he hoped that the critics wouldn’t see it that way. Like any artist, he had some albums that were critical and fan favorites and others that were not as appreciated.

But generally speaking, Sonny was not happy with any of his recordings. There was always this idea that he could do better and would get it better next time. He would eventually find, what he called, “the lost chord” from Jimmy Durante. It’s true that he really struggled with recording. In order to get into a better flow state, he really had to be on stage, in front of a live audience.

I went through the list of drummers he worked with and it was huge. He played with just about every great drummer—Roy Haynes, Philly Joe Jones, Max Roach, Billy Higgins, Elvin Jones, and Shelly Manne, as well as another 30 or 40 accomplished, but perhaps lesser known, ones such as Tommy Campbell or Marvin Smitty Smith. There’s one point where you tell a story how he fired the drummer on the first set and had someone else come on to play the second set. I wasn’t quite aware that he was so tough on the drummers. What do you think that was about?

When I talked with Jimmy Heath, all Jimmy really wanted to talk about was Sonny as a rhythmic player and the way that he innovated with rhythm playing on the saxophone. Just the greatest rhythm player. And what he could do improvising with just rhythm and you can hear that on his solo on “St. Thomas”—the sax just glosses? Playing with the rhythm at the beginning of that solo.

Being such a rhythmic player and such a rhythmic force, he really wanted to connect with the drummer and feel like the drummer was a rock. So sometimes he would kneel over by the bass drum right up against the drums and be playing in kind of a kneeling position which is actually kind of physically demanding. It’s kind of like a yoga pose. He could just stay there—according to a lot of the drummers I talked to—he might just be there for a half hour, just sitting there. Right against the drums. And he would have no compunction about telling them afterwards, “You weren’t making it.” I know that at one point with Roy McCurdy, he started slipping letters under Roy’s door at night: “Mr. McCurdy, you’re not making it.” And the next night Roy would get one saying, “Mr. McCurdy, thank you.”

That’s not verbatim, you’ll have to see what he says in the book, but yes, he was really rough on drummers. Sonny had exacting standards for drummers. You’re right that the list of drummers he played with is kind of unbelievable.

One of Sonny’s greatest inspirations was Coleman Hawkins, who was a hero for him throughout his life. He considered Hawkins the pinnacle. Can you talk about his love and regard for Coleman Hawkins?

He revered Coleman Hawkins, the man they call the father of the tenor sax, starting at a very young age. He discovered Thelonious Monk through Coleman Hawkins. Monk was with Hawkins for a long while.

When he first heard “Body and Soul” come on the radio, because Hawkins had a hit with that and doesn’t even play the melody, Sonny just couldn’t believe what Hawkins was doing harmonically. Sonny realized how intellectually demanding this music could be and went deep into Hawkins, just to study what he was doing. Shortly after hearing “Body and Soul,” Sonny found out where Hawkins lived, not far from where he was living, and he decided to just show up at his apartment with this glossy headshot of Hawkins by this portrait artist named Kriegsman. He waited for Hawkins to show up and got him to sign the photo and that was the beginning of their relationship.

I don’t think they saw each other for a long time after Hawkins signed that headshot. But eventually Sonny had the opportunity to record with Hawkins. And it began as this project to record a number of performances at the Newport Jazz Festival. George Avakian, who was producing these sessions, decided that what came out when Sonny first met Hawk was not what he wanted to put on the record. But then they went into the studio and did Sonny Meets Hawk there.

Documenting that session in the book was one of the kind of revelations for me. The reverence that he had for Hawkins that you always hear about but you really get the feeling of the anxiety he had about going into that session and again, how much he revered the man. Hawkins kind of teaches him a lesson in the recording studio at that time which came out from listening to the studio chatter that has been preserved. There’s this letter that Sonny wrote to Coleman Hawkins that I think a lot of people have read but for those who have not—it’s just beautiful. Where he tells Hawkins what he means to him. Hawkins meant so much to him but then Sonny meant a lot to Hawk as well. They had this ongoing relationship. After Hawkins died, you can also read in the book Sonny’s brief tribute to him. He’s so sad that Hawkins has passed, but he‘s just grateful that he lived and that he had that music to share with the world.

At some point Sonny surpassed him in terms of fame and profile but Sonny, whenever he could, would arrange for Coleman Hawkins to get a gig. He looked out for his hero.

Also, this idea of solo saxophone is something that Hawkins had a precedent for. Sonny had this idea that he wanted to play solo saxophone. He wanted to be like an Andre Segovia on the saxophone. He finally achieves it and he does it periodically throughout his career. He records it but he didn’t feel good about the album that came out of that because I think he was having some dental problems at the time. I really like the album.

The time that we don’t have any recording of to my knowledge that everyone cites as the greatest solo saxophone performance they ever heard, and the greatest one that we’ve never heard, was at the Berkeley Jazz festival I believe in 1969. A number of people were there. I think the pianist Michael Wolff was there. David Murray was there and he heard Sonny play solo that night and the next day he woke up and said to his dad, “I can’t play alto anymore, I’ve got to switch to tenor.” So that was that.

Here’s the 64-Dollar question: Has Sonny read the book and, if so, what did he think? I could see Sonny going, “I don’t know if I want to read it.”

Sonny has an earlier version of the book. He got the longer version of the book. It’s quite a bit longer. He has read some of it, but not very much. He said that it was just difficult to read the story of his own life, which I understand. What we ended up doing because I wanted to make sure that he had an advance copy and that he had a copy before anything had gone to the press is we talked through the book over a series of conversations. I more or less tried to tell him everything that was in the book, so that we could fact check and discuss, or he could add anything else. What happened is that through that process I ended up adding a lot of material from those conversations that made it into the final version. You also get some of Sonny’s commentary after the first draft is finished interspersed throughout the book.

Will he read the final version? We’d have to ask him but I would say that the same way he had trouble being in the recording studio and listening to playback, it might be a little difficult for him to go through and read the story of his life documented the way it is here.

This happens to anyone who lives into their 80s or 90s: there’s a lot of loss. Clifford Brown and Richie Powell, Coltrane, Hawkins, Miles, his mother and father, Lucille, Max Roach and so many different people in his life. He’s outlived even Jimmy Heath. So I’m sure that’s painful.

I think so but he’s committed to continue to represent the art form. In some ways he’s living for that and also for promoting the Golden Rule.