Having just come through the Labor Day turn in the film festival world, which is still picking its way through the pandemic with a mix of in-person and virtual screenings, the industry that depends on festivals is plowing ahead this Fall with plans to release films in theaters and by streaming to a smart TV near you. One way or another, you’ll get your chance to sort out which films live, which ones die and which ones head to the Oscars next March 27.

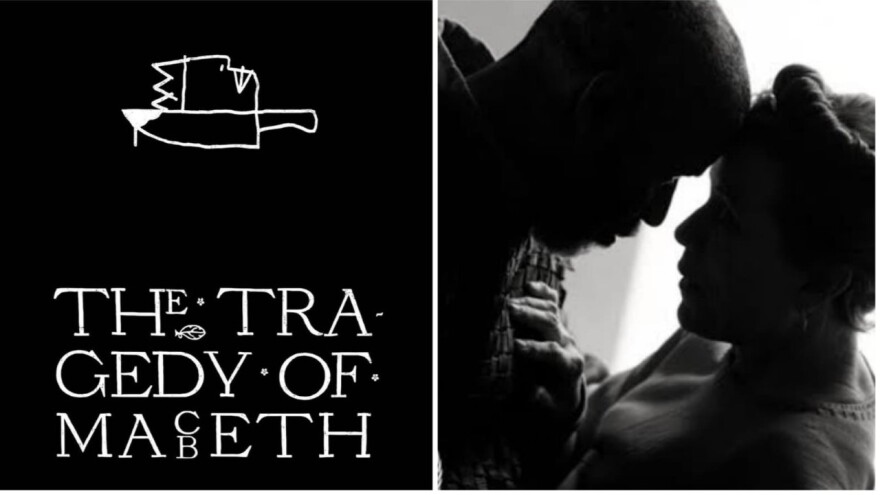

I’ve been to Cannes in July and Telluride over Labor Day in person, and digitally dropped in on Toronto this month, too. And the 59th New York is in progress now at Lincoln Center, having opened with a gala screening of Joel Coen’s Macbeth with Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand in the lead roles.

The Tragedy of Macbeth is an intimidating mountain to climb for filmmakers. Directors because it’s Macbeth, and producers because they should be willing to lose their investment. Think of Roman Polanski’s Macbeth in 1971 with Jon Finch and Francesca Annis, screenplay by Kenneth Tynan, which clocked in at two hours, twenty minutes and pondered monarchy.

There was Aussie director Justin Kurzel, who went from Snowtown Murders in 2011 to Macbeth with Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard in 2015. Three screenwriters on that one, played as a tragedy of generational impatience. Took a bath. And several more highly uninspired takes, till you get back to Orson Welles’ 1948 Macbeth, a minimalist modern take on corruption that was butchered by Republic Pictures, a horror story of Wellesian proportions.

How promising it sounds to open the 59th NYFF then with Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand as Lord and Lady Macbeth in the hands of Joel Coen. Only at 1:45 I am reluctantly persuaded that it has been so compressed that what this Macbeth wants, why he wants it, how the cost undoes him or who in the couple drives the deed – always a ripe area for interpretation in other productions – that this production never quite drives home its tragedy. In his 60s, at the end of his military glory, Macbeth is bewitched by Coen’s brilliant rendition of a contortionist witch and witches, all three played by Kathryn Hunter as if we’d stumbled into the tent of a medieval freak show. Duncan, whom he’s saved, is ripe for the taking, the witch says.

Working without brother Ethan, who ironically is more interested in doing theater, Joel Coen cast the story with half a dozen or so Black actors in roles as consequential as Denzel as the Thane of Glamis, Macbeth, Corey Hawkins from In the Heights and Straight Outta Compton as MacDuff, Moses Ingram unrecognizable from her orphan turn in The Queen’s Gambit, Sean Patrick Thomas from TV as Monteith, and James Udom from Judas and the Black Messiah as Seyton. On the white side, we have Brendan Gleeson, everybody’s favorite tough Irishman, as the Scots king Duncan, played here as the most trusting of souls, and McDormand as Black Macbeth’s striving Lady.

There is Coen’s recognizable enchantment with murder and its impact on the soul going all the way back through Fargo and Blood Simple. However, there’s no appreciable contemporary subtext to the interracial casting: neither as an exploration for Macbeth’s wanting power as a grievance nursed in his skin, nor as a rationalization supplied by his white wife. There’s no radical playing with the idea of a dark heart or a conflicted conscience in a contemporary, beloved black leader’s rise to power. We are not wearing combat boots in a trek here through Barack Obama’s internal conflicts.

You are left with something else, which in its own professional, behind-the-scenes way is what Title 9 is supposed to deliver on the playing fields: color blind casting of great performances by great performers, pure and simple. Race is not being mined here.

Instead, it seems simply part of the black and white designscape of a film presented in what is called the Academy ratio, 1:33 to 1, the more vertical box of classic Hollywood films. Which makes sense in a film about taking power from on high.

In fact, abetted by Carter Burwell’s thundering musical underscoring, drums and strings, this is a visually stunning Macbeth, designed for the screen by rising production designer Stefan Dechant who served on teams for Lincoln and Avatar, by art designer Jason Clark from Mulan and Black Panther, and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel who shot Amelie, one of the Harry Potters and Inside Llewyn Davis and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the latter two for Coen. The writer-director-producer and editor Coen gave the visual artists license in this Macbeth to borrow the abstract angularities and black and white planes of light from German Expressionism, the vertical axis up and down that suggests the religiosity of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent 1928 Joan of Arc, and to drape it all in shadows from film noir. From a distance, from the side, from high, low, and below, one breathtaking formally composed scene of black threading white follows another.

Denzel and Francis hold our attention but more as intelligent curiosities, how could they not? They have worn, beautiful faces, they are us now, not stars, and we watch them up their game from playing outside their characters -- McDormand in Three Billboards, Denzel in any of 100 rogue cop roles -- to internalizing tragic figures recently in Nomadland and Fences. Now here in Macbeth, we can’t take our eyes off their ambition, but still somehow we sit outside it.

In this Macbeth, the fault is not in our stars, but they are eclipsed by the suns of the crafts who set the stage. Go, when A24 releases Macbeth in theaters for Christmas and Oscar qualification, get that in-theatre experience before Apple TV streams it starting January 14.

Finally, one of the pleasures of any festival is finding the small film hiding in a crack somewhere that brings you into the presence of a god. Oh sure, I could be talking about Ken Burns four-part series on Muhammad Ali, which I caught part of at Telluride and is now playing out on HBO. Or how Jane Campion has undone the Western and Benedict Cumberbatch in Power of the Dog, which debuted at Telluride and earned prominent play at Toronto and the NYFF. Or King Richard, the fairy tale version of how Venus and Vanessa William’s dad, Richard Williams, played with relentlessly irritating charm by Will Smith, made sure his girls not just penetrated white tennis but wrecked it.

I’m talking about the pleasure of stumbling through the unforgiving metronome of Toronto’s virtual screening schedule to catch the world premiere of Oscar Peterson: Black + White made by the excellent Montreal producer and doc filmmaker Barry Avrich about a hometown hero. Peterson came up in Montreal, switched from the trumpet after a bout of tuberculosis to the piano, till he heard Art Tatum’s Tiger Rag record that his railroad porter daddy brought home. Peterson thought two guys were playing the piano not just Tatum from Toledo, cried for two months, gave it all up. How Peterson comes to be the Michael Jordan of the jazz piano of the last half of the 20th Century – at 17 playing Jazz at the Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall – is simply a thrilling tour related by the legendary manager Norman Granz, and variously Billy Joel, Jon Batiste, Quincy Jones, Duke Ellington, Ramsey Lewis, Branford Marsalis, Herbie Hancock and Peterson himself.

It just doesn’t get better than this.