Johnny Pacheco, a seminal figure in Cuban-based dance music as it is played in New York City, died on Feb. 15 at Holy Name Hospital in Teaneck, N.J. He was 85.

His wife, Maria Elena “Cuqui” Pacheco, said he died from complications of aspiration pneumonia. As a multi-instrumentalist, studio musician, composer, arranger, producer, bandleader, instrument maker, and co-founder and owner of Fania Records, his influence was ubiquitous.

Pianist, bandleader and Fania All Star Larry Harlow speaks for many when he says: “I learned everything from Johnny. How to be a bandleader, producer, songwriter. How to play this music, everything. Without Johnny what we call salsa today wouldn’t exist.”

Join Bobby Sanabria for a Johnny Pacheco tribute on Latin Jazz Cruise, Friday 9-11 p.m.

Dominican Roots, Cuban Soul

Dominican by descent, Pacheco spent his youth playing accordion as well as the double-headed drum known as the tambora — both staples of merengue, the national music of his homeland. But he would soon become obsessed with Cuban music, as his father, a clarinetist, led a band that at times played the elegant Cuban danzón. A style of music that originally had been played by brass bands, by the 1930s it was played in groups using violins and flute known as charangas.

His boyhood heroes were the charanga orchestras of Antonio Arcaño y Sus Maravillas and Orquesta Ideal. In the trumpet-based conjunto style that played son (the folksong root of salsa) were Arsenio Rodríguez, Chapotin y Sus Estrellas, and La Sonora Matancera, which he all heard on short-wave radio.

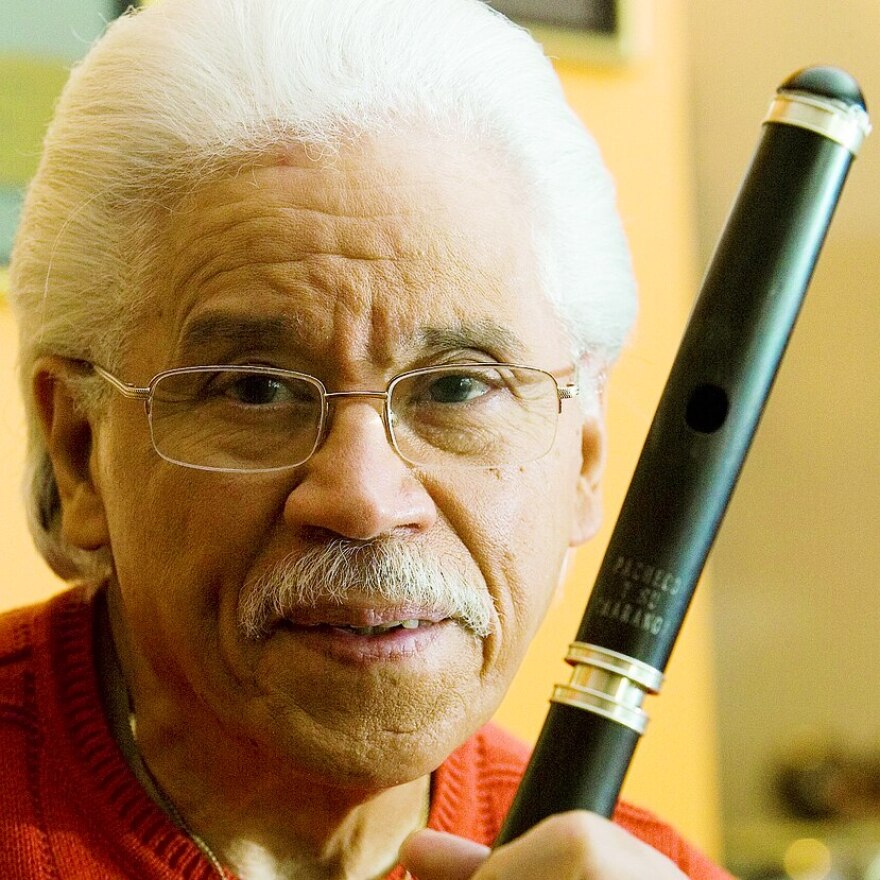

In an interview conducted by David Carp and Bruce Polin for the Descarga Newsletter in 1997, Pacheco recalled that his father used to get charanga arrangements from Cuba. “They often had clarinet instead of the flute playing the lead,” he said. “My father used to play the lead being that he played clarinet.” Pacheco would soon master the complete battery of Cuban percussion as well as drumset, alto saxophone, clarinet, violin, and the instrument that became his calling card, the flute.

Juan Azarías Pacheco Knipping was born March 25, 1935 in Santiago De Los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic. His father, Rafael Azarías Pacheco, was the renowned bandleader for the Orquesta Santa Cecilia, which is credited as the first orchestra to record the most famous merengue of all time, Luis Alberti’s “Compadre Pedro Juan.” His mother, Octavia Knipping, was of French, German, and Spanish descent.

At age 11, Pacheco moved with his family to New York City — specifically, the Mott Haven section of the South Bronx, where he attended P.S. 124, P.S. 51 and Bronx Vocational/Alfred E. Smith High School. The neighborhood was a hotbed of musical talent consumed by mambo. Pacheco’s boyhood friends included percussionists Ray Barretto, Ray Mantilla, Manny Oquendo and Orlando Marin; pianists Charlie and Eddie Palmieri; and many others.

By 1958, Pacheco had replaced Willie Bobo in the bongó chair with the Tito Puente Orchestra. He’d also begun formal classical percussion lessons at the Juilliard School with Morris Goldberg. Because of his sight-reading abilities, he quickly became a go-to percussionist in the New York City studio scene, playing on record dates by Pérez Prado and Xavier Cugat — and a staff musician at NBC, frequently called when extra percussion was needed in the Tonight Show Orchestra. He later appeared on jazz albums by the likes of pianist McCoy Tyner and guitarist Kenny Burrell.

Pacheco was also making his own instruments — bongos, congas, timbales — and a series of cowbells that became legendary. They were made from a special metal used on airplanes, which Pacheco refused to reveal while he was alive.

The Tritons

Noted album-cover artist, magazine owner, and Fania All Stars emcee Izzy Sanabria (no relation to yours truly) recalls:

I knew Johnny from P.S. 51. He was part of the gymnastics, tumbling club. He had formed his own charanga group where he concentrated on playing flute, and it was the hottest thing. Johnny was a showman when he played, and he drove everyone nuts on the dance floor. I was the emcee and bartender at the Tritons Club in the Bronx, and he had told me that he had his first album coming out. I designed a cover for it but the head of the company, Al Santiago, already had someone do it. I asked Johnny to let me show it to Al. When I showed him what I had donem he flipped. Al screamed: “That’s it! Forget about the other cover, that’s it!” I had captured Johnny in all the ways he moved, stood…I based it on an African woodcut with him holding the flute and placed the drawing over a Kodak yellow background.

That illustration became a turning point in Latin album cover art for which Izzy would become famous. Recorded for Al Santiago’s Bronx-based Alegre Records, Pacheco Y Su Charanga, would sell more than 100,000 copies in less than three months. The group appeared on the gamut of network television shows: Ed Sullivan, Merv Griffin, Clay Cole and others.

The Tritons Club, located over the Spooner Theater in the South Bronx, became the center of activity for a weekly weekend descarga (jam session) that Pacheco would run. It attracted the finest Latin musicians in New York City. It would lead to a series of now-classic albums produced by Al Santiago of Alegre Records; the Alegre All Stars featured players like trombonist Barry Rogers, tenor saxophonist José “Chombo” Silva and more.

The Birth of Fania

But it was the formation of Fania Records that would cement Pacheco’s place in the annals of Latin music history. Record executive and producer Alex Masucci explains: “We were from Bed-Sty, Brooklyn. My bother Jerry had joined the Navy in 1952 and had been stationed in Cuba. That’s when he fell in love with Cuban music and culture. After he served, he became a New York City Police Officer and then began studying law. In 1958,, he had graduated and went back to Cuba. By 1960 he had gotten a job working for Castro as a P.R. man for the Cuban Office of Tourism.” The subsequent economic and travel embargo imposed on the island by the United States would squelch Masucci’s plans. As Alex recalls:

My brother started working for a small firm led by Bert Parisa in Manhattan. The address was 305 Broadway. Johnny was looking for a lawyer because he wanted to start a company. He met Jerry at a party for Artie Kapper, who my brother had met in Cuba, and had some ties to the record business. My bother and Johnny hit it off. They borrowed money from my mother to start the company. The first office for Fania was a broom closet in Bert’s office. They used to make the deliveries out of the trunk of Johnny’s used Mercedes.

Officially formed in 1964 with Pacheco and Massucci as co-owners, Fania Records entered the market with Cañonazo (Cannon Shot), by Johnny Pacheco’s newly formed two-trumpet conjunto replacing the violin-and-flute charanga sound. Signings of local artists like pianist Larry Harlow and percussionist Ray Barretto grew the company’s visibility — as did its stable of Latin Boogaloo artists like vocalist Joe Bataan and upstarts like trombonist Willie Colón.

As recording director, Pacheco eventually produced and oversaw hundreds of releases. In 1974 he signed Celia Cruz, the Queen of Salsa, and his production skills revitalized her career with the megahit album Celia and Johnny. “What Johnny did was bring back that típico Cuban conjunto sound,” says Izzy Sanabria. “That first album with Celia is a great example of that.” The constant steady growth of the company had music journalists declaring Fania “the Motown of Salsa.”

The Cheetah

On Aug. 26, 1971, Fania assembled its best bandleaders, who each picked their lead vocalists with two sideman — thus forming a supergroup they called the Fania All Stars. Pacheco acted as musical director and ringmaster. The concert, at New York City’s Cheetah Club, was recorded and released as an album. “Ralph Mercado ran the Cheetah and he didn’t want to give Jerry Saturday night,” recalls Alex Masucci. “He gave us a Thursday. He told Jerry, ‘I want the door and the bar.’ Jerry said ‘OK.’ The line was around the block several times.” At the suggestion of Harlow, the concert was filmed.

The success of the subsequent theatrical release, Our Latin Thing, shed a light on the transformation of Cuban music by the city’s Puerto Rican community. “I give full credit to Izzy,” Masucci says. “He started using that word ‘Salsa’ to promote the music. It was organic when it first started and then we made a conscious effort to use it in all our promo. It was born that night at the Cheetah.”

Yankee Stadium

On Aug. 23, 1973, the Fania All Stars under Pacheco’s musical direction played at Yankee Stadium in a concert that was attended by over 40,000 people, becoming instantly legendary. Larry Harlow recalls: “The people rushed the stage because they got so excited with the music going on, because Ray Barretto and Mongo Santamaría were having a conga duel on my tune ‘Congo Bongo.’”

Alex Masucci: “That’s me you see in the film yelling at Johnny to stop the concert, because we had to pay the Yankees a big fine if the people rushed the stage. All the instruments, everything was stolen.”

Harlow: “We had three more numbers we were supposed to do. We never finished the concert. But it was incredible.”

Salsa — a subsequent concert film of the Fania All Stars at Yankee Stadium and in Puerto Rico — would later shed even more light on the genre. And under Pacheco’s baton, the All Stars traveled to Europe, South America, Africa and Japan, in a series of successful tours performing in stadiums to audiences rivaling that of major rock acts.

“Johnny was a sparkplug,” attests Sanabria, describing Pacheco’s presence as conductor. “He was a complete entertainer and got the audience going by playing and dancing — just like when I first saw him at the Tritons.”

Aurora Flores — noted music journalist, bandleader, and former staff member at Fania Records — adds that Pacheco also brought a human dimension. “Johnny had a unique sense of humor that belied his musicianship,” she says. “He was always joking around, and it was infectious with audiences.”

After changing the course of Latin music history, being honored by his native country and awarded a Latin Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (among other accolades), Johnny maintained a simple philosophy towards music “I feel that less is more,” he said. “You don’t need too many notes to make the tune swing. And the other thing is, there’s nothing wrong with swing — the best swing is a slow tempo but played right. Like a real son montuno, guaguancó. That music’ll wake up the dead.”

Maestro Pacheco is survived by his wife, Mara Elena; two sons, Elis and Phillip; and his two daughters, Norma and Joanne.

Special thanks to Aurora Flores, Izzy Sanabria, Alex Masucci, Larry Harlow, Ruth Sanchez, Elena Martinez, and the entire Pacheco family.