We thank our readers for following Deep Dive with Lewis Porter.

Sometimes new information comes to light after I’ve posted, and at other times I simply think of something I’ve left out. So periodically I’ll collect these stray findings in an update, this being the first.

More on “JAZZ”

In my post on the origins of the word “jazz,” I mentioned that it can first be found among white sports writers in California (not among African-Americans, and not in New Orleans), and that every other theory about the word’s origins is false. My focus here is on how the word may have migrated from California to Chicago, where it was first applied to the music. I noted then that story “will be covered in a future post.” Here are those promised details:

As lexicographer Ben Zimmer has noted, the word “jazz” may have been brought from California by white banjoist Bert Kelly (1882-1968), who claimed to have used it to name his Chicago band in 1914. (Kelly never recorded but became widely known when he founded the nightclub Bert Kelly’s Jazz Stables, aka Kelly’s Stables, first in Chicago and then in Manhattan.) In Chicago “jazz” was first printed in 1915, with reference to bands such as white trombonist Tom Brown's, which hailed from New Orleans.

But there are several complexities and uncertainties to this story. First, there is no source for Kelly’s claim other than his own word — and he was a braggart who titled his unpublished memoir “I Created Jazz.”

In a 1919 article, close to the era we’re discussing, it is reported that Kelly first named his group a jazz band in the fall of 1916, which would be a year too late to be the first! And he was a likely source for this article. (The article also says 1915, but that appears to be a typo. Another article from 1919, published anonymously in Literary Digest, says Fall 1915, which is also too late to be the first.) Further, the article is written by Walter Kingsley, who, despite identifying himself as “head of the bureau of research” of the Keith Vaudeville Circuit, was in fact the well-known press agent of that organization. I already noted in my previous post that Kingsley’s articles were intended to be entertainment, not scholarship.

The first printed use of the word applied to music occurs in Chicago on May 22, 1915, in an ad for Lamb's Café; Tom Brown’s band was playing there. But the band is not mentioned, and the ad does not say “jazz” — it says “JAD ORCHESTRA.” Nobody knows why, but it’s likely a typo.

The next ad, on May 26, does mention “Brown's Band,” but says “From New Orleans...Playing Dance Music.” There’s no use of the word “jazz.” Finally, on July 11, 1915, there's a full article about “jazz and blues music” (with no bands specified by name).

In short, it’s not known how the word traveled to Chicago, and for all we know there could have been any number of people from California who knew the word that moved to Chicago at the time. Bert Kelly’s claim that he used the word first might indeed be true, but there’s no evidence for that — other than the fact that before coming to Chicago, he had in fact been around the baseball players who used the word. And I admit, that is a big point in his favor!

Revisiting Duke Ellington and “Lazy Rhapsody”

You may have noticed that in the Duke Ellington Orchestra’s 1932 radio broadcast, at the bridge of “Lazy Rhapsody” (6:29) Duke’s piano is joined by a booming “foghorn” effect.

The sound heard at the end of the track (6:39) is the same, and in the same pitch, A-flat. We don’t know what this is. I note that the theater had a pipe organ, so I would venture that the organ might have produced this sound — assuming Duke had the idea in advance of using the organ, and worked out a way to have that note played at a certain moment. (Lawrence Brown was present but not performing in Hartford; it was his first night with the band. Is it possible that he was asked by Duke to hit that note on the pipe organ?) Also, there is distortion just before the break in the recording, 36 seconds in. That sounds like perhaps some kind of electrical issue, but we really don’t know what it is.

Steven Lasker has done further research on the writing of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South.” The Rene brothers were musicians, songwriters and founders of recording companies. Otis died in 1970 but Leon Rene lived until 1982, and luckily he was interviewed. He said that he and Otis collaborated on “Sleepy,” with Otis providing the melody. As for Muse’s co-credit, he may have been present when “Sleepy” was written. We mentioned that he claimed the song “was born in 15 minutes.” And since he premiered the song and performed it every night for the two weeks that the show ran, it's easy to imagine he suggested a change or two in the lyrics or melody, thus earning his co-credit.

Lasker has also made another amazing Duke discovery — two songs recorded in 1925 by a white vaudevillian, on which Ellington is quite likely the pianist.

A Would-Be Presidential Appointment

Finally, let me share a press announcement that is not known to any Ellington experts I’ve consulted. It states that Lester Young, Thr President of the tenor saxophone, was slated to join Duke’s band in 1942!

This never happened, of course; after Barney Bigard left in early July, he was replaced by Chauncey Haughton. But what’s most interesting is that the article — in the Pittsburgh Courier, July 11, 1942 — reports that Pres had agreed to join the band, not that it was merely a possibility. Duke and Pres could have crossed paths when both were in Los Angeles in Dec. 1941. And in July of ‘42, Pres’s stint with his brother Lee’s band was ending, and he moved to back to NYC by October.

Pres was so closely associated with Basie — as closely as, say, Johnny Hodges was with Duke— that it’s astounding to think such conversations were going on. And notice, the press release doesn’t suggest that this would have been a one-time guest appearance, but that Young would have been a regular member of Duke’s band. Young would have been available, because in 1941 and 1942 he was not with Basie, but performing in a small group co-led with his drummer brother Lee — most recently, as the article notes, at Kelly’s Stables!

This unknown little news item boosts our knowledge of how widely Lester Young’s genius was appreciated. Before Basie, Fletcher Henderson had reached out and hired him (it famously didn’t work for more than a few months — but still, it happened). Then came Basie. It isn’t widely known, but Benny Goodman indicated that Young was his favorite saxophonist, and Basie’s his favorite band; it’s no accident that they were guests at Goodman’s famous Carnegie Hall concert in Jan. 1938. That fall, Goodman reached out with an offer (and a recording session, not issued until 1972) to actually hire Pres, Basie, and other Basie band members for his own band. And now we can say for certain that Pres was also admired by a Duke.

More on Monk

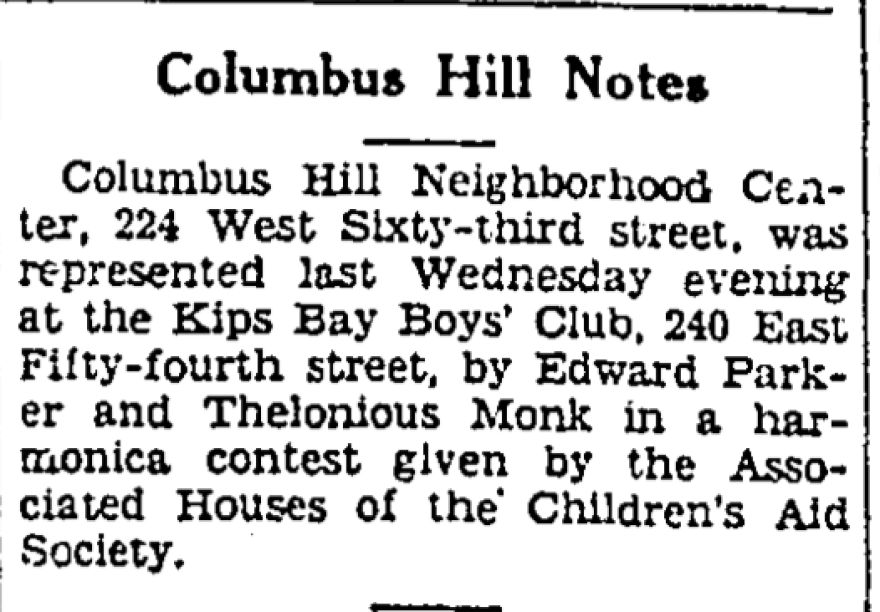

Here’s a tidbit about Thelonious Monk that’s not well known, and not included in my friend Robin Kelley’s outstanding biography. Monk played harmonica as a youth, well enough that he entered a little contest! Here’s the announcement in The Amsterdam News from March 5, 1930.

We don’t know anything about Edward Parker, but Kelley does mention the Center in strong terms, saying that “Besides his mother, the most important influence on Monk’s early development as a musician and as a young man wasn’t a person but an institution – the Columbus Hill Neighborhood Center (renamed the Columbus Hill Community Center in 1933).” This no longer exists, but my former graduate student Cherise Harris determined that the Kips and Children’s Aid organizations still exist, at new addresses.

Peter Keepnews, jazz historian and son of Monk’s important record producer Orrin Keepnews, has written that Monk’s father, Thelonious Sr., played blues and train sounds on the harmonica. Peter notes observantly that “Train sounds would later occupy a prominent place in the Thelonious Monk oeuvre; indeed, he built entire compositions around pianistic versions of such sounds — notably ‘Little Rootie Tootie.’ …The open chords characteristic of the harmonica found a frequent echo in Monk’s writing and playing.”

So the discovery that Monk played harmonica as a youth makes sense, and has significance both in the context of his family as well as in his musical development.

Here too is an addendum to my “‘Round Midnight” post: There is an earlier recording that uses almost the same introduction that Dizzy added to Monk’s tune.

In the post I traced the famous introduction and ending of “‘Round Midnight” to various Gillespie recordings going back to Jan. 1945. But jazz photographer Michael Wilderman has pointed out that saxophonist Georgie Auld recorded a feature for himself with his big band, “Concerto for Tenor,” that uses a similar sequence of chords as the Dizzy intro, played both as intro and ending.

In this case only the first two of Dizzy’s three phrases, each a whole step lower, are stated, with two extra measures between them. Then the piece moves on differently, changing, incongruously, into a fairly standard “rhythm changes”-style swing tune at 55 seconds in, which reminds me of the Woody Herman band. The piece then slows down again and the intro comes back at 2:14.

This was recorded on May 22, 1944 — more than seven months before the first Gillespie example. And it’s not by Gillespie! Both the tune and arrangement are credited to saxophonist Budd Johnson.

By the way, I am a huge fan of Budd Johnson (not to be confused with the popular R&B pianist and bandleader Buddy Johnson). I used to see him play all around New York City, and loved his playing! Born the same year as Lester Young, 1909, he was unique in that he actually changed his style and became one of the earliest Pres disciples. (All of Young’s other disciples were of the younger generation.)

But before you jump to the conclusion that it was Budd after all who invented this sequence, and not Dizzy, let me make the following points:

- Through his interest in Pres, Johnson also got into bebop early, and was associated with Dizzy. In fact, both Budd and Pres played at different times in Dizzy’s first bop quintet on 52nd Street. Johnson can be heard on a version of “A Night in Tunisia” preserved from a Gillespie radio broadcast in Jan. 1944.

- Budd was a notable early bop composer. His “Bu-Dee-Daht” (Budd-Dee-Dot—get it?) was recorded under the leadership of Coleman Hawkins at the same session where Dizzy premiered his “Woody 'n You” in Feb. 1944, three months before the “Concerto” for Auld.

- Recall from my previous post that “Woody ‘n You” was the first instance of this sequence.

- Also note that Dizzy and Auld were associated: they both recorded behind Sarah Vaughan on Dec. 31, 1944, and Dizzy recorded with Auld’s big band in Feb. and March 1945.

- In the many decades that both Budd and Dizzy were active after 1945, nobody ever disputed that the introduction (and ending) of “‘Round Midnight” are by Gillespie.

In short, I think it’s fair to say that Budd took an idea that Dizzy was working on and adapted it (it’s not the same, after all) for his own “Concerto.” There’s nothing wrong with that, and we thank Michael Wilderman for sharing this valuable discovery that fills in more of the history of this passage!

Dr. Lewis Porter is the author of acclaimed books on John Coltrane, Lester Young and jazz history, and has taught at institutions including Rutgers and The New School. He’s also a pianist whose latest album, Solo Piano, will be released on March 29.