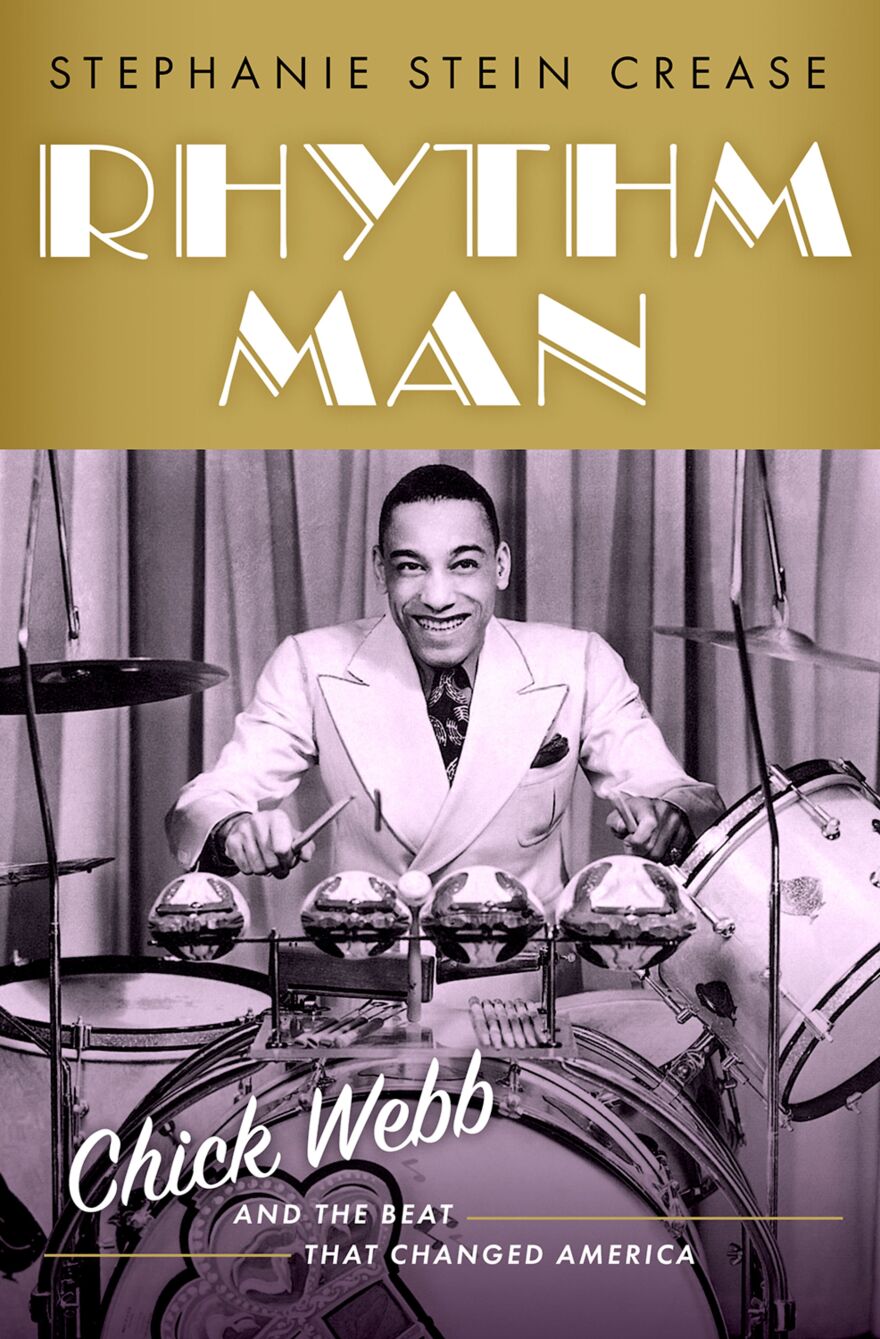

An Excerpt from 'Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat That Changed America' by Stephanie Stein Crease

By Ella Fitzgerald’s 18th birthday on April 25th, 1935, drummer/bandleader Chick Webb had already given the teenage singer a life-changing gift. She’d been scraping by on her own in Harlem, even after winning first prize at the Apollo Theater’s Amateur Contest in November 1934. A few months later, Webb was finally convinced to listen to her sing, urged on by a couple of his sidemen. In early March 1935, Webb gave Ella her first “live” tryout with his band, playing for a fraternity dance at Yale University. A couple of weeks later, he hired her after a longer tryout at his orchestra’s home base, the Savoy Ballroom. Now a member of the Chick Webb Orchestra, Ella starting charming audiences at the ballroom, where she often danced alongside the band. Within three years, photos of this contrasting pair, with Ella towering over the 4-foot “King of the Drums,” were in newspapers all over the country, as Webb’s band featuring the young singer achieved national stardom. None of this happened overnight.

Ella was no great shakes when she started. —Helen Clarke

Yes, I loved the music, and at the time, I loved the idea of people applauding for me. I don’t think I really realized what was happening to me. When you’re that young, it happens in such a way that you can’t explain it. You don’t believe it’s happening to you! —Ella Fitzgerald

In 1935, when Ella Fitzgerald joined Chick Webb’s orchestra, a handful of female jazz vocalists with big bands were making more of an impact: Ivie Anderson with Duke Ellington; Mildred Bailey with Casa Loma, the Dorseys, and her husband Red Norvo’s band; and Helen Ward with Benny Goodman’s new orchestra. Billie Holiday had yet to sing with a big band, but was ascending as a star for her recordings with Teddy Wilson’s small band: “I Wished on the Moon,” and “What a Little Moonlight Can Do.” A few years later, female singers were regular members of otherwise all-male big bands. But in Ella’s first two years with Webb, as one of the first swing big-band singers, she had carte blanche developing her style and skills.

Dick Vance, one of Webb’s chief arrangers for Ella and lead trumpet for Webb’s band from fall 1938 to 1939, first heard Ella with Webb’s band in 1935 when he was briefly with one of the alternate bands at the Savoy. “I had never heard anything like her in my life. She was a complete departure from ragtime singers or blues hollerers—they were still the thing that year. Sometimes I’d forget to come in on my own parts! At first, she was just a marvelous singer, and when I came into the band later she was even better. She was one of the most talented people musically I have ever seen.”

Vocal arrangements were a small portion of Webb’s book when he first hired Ella Fitzgerald. Taft Jordan usually sang an Armstrong-style hit or two over the course of a night, and Charles Linton performed two or three “sweet” numbers during each set, which were still as crowd pleasing as the band’s hot numbers, even at the Savoy. Other Black “sweet” male singers were on the scene, and this didn’t seem like a passing fad. The Chicago Defender reported: “Harlem Chirpers Prove It’s Sweet Singing Fans Prefer: Has the present trend of vocalizing turned to sweet singing? . . . No longer do the hoarse and husky voiced singers clutter the airwaves. . . . Today there are sweet, smooth and pleasant voiced singers accompanying our leading orchestras. There is Orlando Robeson, the smooth voiced young man with Claude Hopkins, Harlan Lattimore, the golden tenor with Don Redman, Chuck Richards, the sepia Bing Crosby with the Mills Blues Rhythm Band, Charles Linton, the lilting voiced chap with Chick Webb, and the newest member of the present crop, the high-pitched Herbie Jeffries with Ralph Cooper’s Orchestra.”

At the same time, audiences at the Savoy really liked Ella Fitzgerald. Webb asked Edgar Sampson and his other arrangers to customize new charts to highlight her in light-hearted material that could swing. He didn’t need her to sing slower ballads or torch songs—Linton fulfilled that role.

Ella’s first months with Webb’s band are as difficult to document as Webb’s own early months as a bandleader. Judith Tick, in her forthcoming new biography of Fitzgerald, Becoming Ella Fitzgerald, challenges the notion that Ella did not have agency—that she was shy, willing to sing anything, and awkward about finding her role in the band. To jump into this new existence, she had to be confident, single-minded, and as ambitious in her own way as Webb was. Her shyness may have been her cover to keep her own counsel amid waves of advice.

"Her shyness may have been her cover to keep her own counsel amid waves of advice."

Varying points of view about Ella’s introduction to Webb persist in a Rashomon-like kaleidoscope. Drummer Kaiser Marshall had also urged Webb to hire Ella—“You damn fool, you better take her”—along with Bardu Ali, Charles Linton, and Benny Carter, who’d already made their pitches. Once she was in the band, Webb’s musicians accepted her and thought of her as a younger sister (they even called her “Sis”). Most of them quickly realized how gifted she was in this relatively new idiom—big band swing plus swing-style vocalist.

Ella Fitzgerald was lucky, after a risky year when she essentially lived on the streets. Moe Gale rented a room for her at the Braddock Hotel on 126th Street, right near the Apollo Theater. Sally Webb helped her find the right clothes and helped coach her about stage presence. She and the Savoy hostesses welcomed Ella into the Savoy “family.”

Just as Fitzgerald entered Webb’s world, Webb had plenty of airtime on nationwide radio and live Savoy broadcasts, and she was soon heard singing on the air. Radio was the best way that the Gale Agency promoted its Black artists. A Gale Agency press release picked up by several papers boasted: “Radio contacts of Gale, Inc., artists’ representatives, have brought national popularity to more colored artists than any other single source.” The release mentions that “the Four Ink Spots, Chick Webb and Willie Bryant are examples of performers under Gale’s managerial wing who have risen to national fame.”

Willie Bryant had been a familiar stage presence in Harlem but had only recently become a bandleader. A handsome loose-limbed six-foot- tall dancer, comedian, and M.C. nicknamed “Long John,” Bryant took over the leadership of Lucky Millinder’s band after Millinder was asked to lead Mills Blue Rhythm, an Irving Mills ensemble. Bryant had a radio fan club with thousands of followers, the “Hoppin’ John Club.” The Ink Spots, an early model and forerunner of Black R&B vocal quartets, had some radio success in Indianapolis when they decided to come to New York to seek a recording contract. Moe Gale took great pride in discovering the group and kickstarting their career on national radio.

Gale’s contacts in radio helped Gale advance his own career as an artists’ manager “specializing” in Black artists. One has to give some credit to Gale for creating opportunities via radio, a career-launching medium, at the same time that he and his company, Gale Inc., perpetuated the “white gatekeeper” role in the entertainment business. The editor of the Pittsburgh Courier reported:

It was at the Savoy that young Gale came in direct contact with colored bands and saw the opportunity for wider popularity than that achieved at the Harlem dance palace. . . . Gale has played his part in discovering new talent, also. He took the “Four Ink Spots” when they were unemployed and built them up to where they demanded $1750 a week, and at the same time filling a 3x a week sustaining program on NBC. . . . He watched Chick Webb grow from Harlem popularity at the Savoy to national fame. And Moe Gale believes there is an even greater future awaiting colored artists.

In May 1935, Webb’s band was booked in and out of New York, including dates in Washington, DC, where the band “will be heard by special arrangement of the National Broadcasting Company, on a nationwide hookup from Washington on his regular Radio City broadcast, May 16. Chick and his Chicks will charm the ether waves from the capital from the regular NBC station there.” Although this hook-up was a technical matter—Webb was in the city— it’s a testament to his on-air popularity that the network set it up. Webb, like other Black artists, could not get a national sponsor. But Webb’s frequent airtime on sustaining programs, and the blizzard of attention from his appearance at the Metropolitan Opera gala, brought him widespread coverage in Black and white newspapers and trade magazines. Between 1935 and 1936, “Stompin’ At the Savoy,” was played on the air over 10,000 times.

That spring, Webb and his orchestra went to New England—Ella’s first trip with the band since she was hired—pinch- hitting for Willie Bryant’s band, who left their own tour to perform at Detroit’s Greystone Ballroom. On this trip to Boston, Providence, Rhode Island, and Portland, Maine, Webb’s audience was mostly white. Ella Fitzgerald started getting her first press notices. The Pittsburgh Courier reported: “Not only did Chick’s music go over, but the entertainment afforded by Charles Lynton, Ella Fitzgerald and Taft Jordan, members of his barnstorming crew, made the Easterners gape. . . . The people down East were greatly surprised on seeing Chick, but admired him all the more when they got a sample of his rhythm and saw him in action. Now famous as the ‘midget’ bandmaster, Chick’s half-pint size usually sweeps the newcomers off their feet. But they are calmed down in a grand rush when Chick begins waving his baton.”

The band’s live performances closed the disconnect between Webb, the invisible radio star, and Webb, the “half-pint midget bandmaster.” It was surprising for audiences to see Webb in person after only hearing his band on the radio. This was Webb’s gift and challenge as he made his way into national fame. One wonders if Webb actually kicked the band off with a baton or the press was exaggerating (not unusual). Webb didn’t need to prove his conducting skills with a baton at the Savoy—he led from the drums.

From Rhythm Man by Stephanie Stein Crease. Copyright © 2023 by Stephanie Stein Crease and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.