Legendary saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter died on Thursday, March 2 in Los Angeles. He was 89 years old. Shorter had been facing numerous health challenges in recent years.

Shorter’s legacy in the jazz community stems not only from his distinctive and influential saxophone sound, but also his work as a composer, with many of his compositions such as “Footprints,” “Infant Eyes” and “Fall” becoming jazz standards played by countless artists and bands at all levels. In addition, the beloved Shorter was a member of arguably four of the most important jazz groups in modern jazz, starting with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers (1959-1964) and leading to -Miles Davis Quintet (1964-1970), Weather Report (1971-1986) and the Wayne Shorter Quartet (2000-2019). His lifelong friendship and collaboration with Herbie Hancock, originally forged as members of Davis’ famed “Second Great Quintet,” produced numerous notable performances and recordings including many seminal Blue Note Records sessions, a later duo album 1+1, as well as cameos on albums by Joni Mitchell and others.

“Wayne Shorter, my best friend, left us with courage in his heart, love and compassion for all, and a seeking spirit for the eternal future," said Hancock in a public statement issued immediately after Shorter’s passing. "He was ready for his rebirth. As it is with every human being, he is irreplaceable and was able to reach the pinnacle of excellence as a saxophonist, composer, orchestrator, and recently, composer of the masterful opera ‘…Iphigenia’. I miss being around him and his special Wayne-isms but I carry his spirit within my heart always.”

Shorter was born on August 25, 1933 in Newark, N.J and raised in a working class background. His mother worked for a furrier and his father was a welder, but the latter encouraged his son (and brother Alan) to pursue their interests in the arts. Shorter went to Arts High School in Newark ostensibly to pursue the visual arts. He had won an art competition as a 12-year-old and was encouraged by one of his teachers to apply to the program. However, once there, the young man’s attention wavered. “I walked to school,” Shorter told WBGO’s Nate Chinen, “and often found myself walking past the school, going around the corner to where the Adams Theater was, to go see a movie and a stage play. I would skip some classes, but not the whole day: I went into the school building when I knew it was time for a certain class.”

Eventually inspired by a teacher with the remarkable name of Achilles D’Amico, he got serious about playing music. It didn’t hurt that he had been exposed to great music around the house and in the neighborhood. The sounds of artists like Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie and Duke Ellington were in the air in Newark and many Northeastern cities. Like many a saxophonist, Shorter started out on clarinet, switching over to tenor saxophone, while his brother Alan played alto. The two began playing around town with local bands such as the Nat Phipps Band and Curtis Bland, the latter a retired football player. Shorter went on to study at New York University where he received a degree in music education. But for the rest of his life, his education would largely come from the bandstand and his own personal explorations and collaborations.

Shorter served in the U.S. Army for two years, and amazingly played with pianist Horace Silver during that time. (The two veterans would both later create jazz history with their recordings for the Blue Note label.) Coming back to NYC, Shorter would jam with fellow young saxophone explorers Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane and gain a reputation and even a name as “The Newark Flash,” based on his precocious chops. After a brief stint with Maynard Ferguson, in 1959 Shorter joined one of the great graduate schools on post-bebop: Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. He replaced Hank Mobley (who had in turn replaced Benny Golson) in the saxophone chair in a band comprised almost entirely of Philadelphia jazz players – pianist Bobby Timmons, bassist Jymie Merritt and trumpeter Lee Morgan. Together for about five years, this group is considered one of Blakey’s finest in his long career as a bandleader. Somehow, they managed to record more than a dozen albums, mostly for Blue Note Records, and helped to establish a sound and sensibility for that label. As a gifted and prolific composer, Shorter evolved into the music director for the group and contributed many tunes to the group’s book, including several that the group would play for years afterward.

Towards the end of his tenure with Blakey, Shorter began recording albums for Blue Note as a leader, featuring many of the greats in that label’s stable of musicians. But it was his joining Miles Davis’s newest quintet in 1964 that would shapeshift not only his own career, but the direction of jazz itself. Along with bandmates Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams, Shorter added a quintessentially modern touch to Davis’s music, moving away from more steady time signatures and chord changes to more floating rhythms and knotty yet evocative melodic lines. The recordings (and performances) by the quintet, such as Nefertiti, Miles Smiles, E.S.P., Sorcerer and Filles de Kilamanjaro, are often found in Top Ten or Desert Island Discs lists. Shorter’s powerful sound and quirky phrasing, along with his unique compositions, were a central part of that canon, including "Footprints," performed by the quintet in 1967, seen here in a performance by the quintet in Sweden in 1967:

As the ‘60s came to an end, the influences of rock, funk, R&B and even world music began to find their way into Davis’s music and into those of at least three of his sidemen—Hancock, Williams and Shorter—who each would eventually leave to form their own bands (Headhunters, Lifetime and Weather Report) that fused all those styles, thereby giving name to a new genre—fusion. Shorter had met keyboardist Joe Zawinul in one of Miles’ later bands and the two formed Weather Report to explore this new style that not only drew upon all of those genres, but also created a particular sound in which the bandmembers seemed to all be soloing at once. Again, Shorter would quietly impose his sound upon the group, both from his saxophone playing, which then included more soprano, and from his remarkable compositions. Yet as the years went by, Shorter seemed to defer more and be a bit less prolific, whether due to Zawinul’s alpha-male personality or Shorter’s own personal issues.

The group featured several different rhythm sections, but it was the addition of Jaco Pastorius and Peter Erskine that lifted the group into rock star status, in no small part because of Pastorius’s charismatic sound and stage presence. Jaco and Erskine were succeeded by Victor Bailey and Omar Hakim, who would form the final iteration of the influential group, which spawned dozens of jazz rock bands with names, from Passport to Azymuth to even the Yellowjackets.

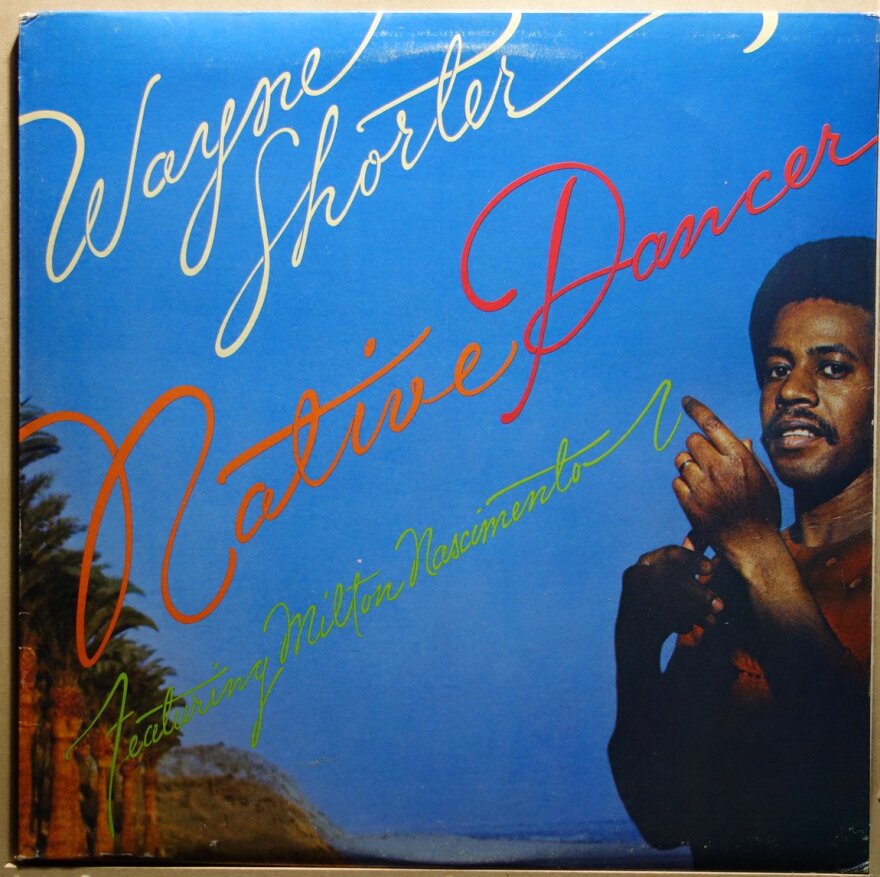

Between tours and recordings with Weather Report, Shorter would also tour with the V.S.O.P. group, a sort of reboot of or tribute to the Miles Davis Quintet, featuring Freddie Hubbard in the trumpet chair. Shorter also began contributing as riveting soloist to Joni Mitchell’s albums and took an iconic turn as a soloist on Steely Dan’s Aja album. In addition, he established a musical and personal relationship with Carlos Santana with whom he recorded and later toured as co-leader of the Santana – Shorter Band. Another important collaboration away from Weather Report, but very much in the same vein, was Native Dancer, Shorter's iconic album with Milton Nascimento, which was released in 1975 and featured songs from both men, backed by Hancock, Airto Moreira and other notable players.

After Shorter left Weather Report in 1986, he went on to record a succession of electric jazz albums for Atlantic that somehow managed to disappoint both old fans of his acoustic Blue Note discography and younger fans of his work with Zawinul and Weather Report. Yet, the three albums—Atlantis, Phantom Navigator and Joy Ryder—include many of his notable compositions that he would return to with later groups and feature a veritable who’s who of contemporary jazz, including John Patitucci, Terri Lyne Carrington, Vinnie Colaiuta, Jim Beard, Patrice Rushen, Nathan East and Rachel Z. Most of these artists would continue to work with him in his future projects, both electric and acoustic.

Shorter would record one more album in an electric high energy mode – High Life – produced by Marcus Miller and released by Verve. All of these albums hold up very well and would achieve later acclaim for their innovative compositions and dense arrangements, despite the occasional critical beating they took in the jazz press, which year after year seemed to lament Shorter’s abandonment of the acoustic jazz format. Little did they know that Shorter would return to playing acoustic jazz with one of the most dynamic small jazz groups of the 21st century.

[Personal side note: In 1995 I appeared with Marcus Miller on a TV show on the BET on Jazz channel and while in the green room, I asked Miller what he had been doing lately. He said that he had just finished a record with Wayne Shorter. I said, “That sounds great.” He said, “It is great, but jazz people are going to kill me for it because they want to hear Wayne play acoustic music.” I said, “No, people love Wayne and love what you do as a producer.” Miller was right. In a well-known and widely circulated piece by Peter Watrous for The New York Times, the album was lambasted for burying Shorter’s talents in contemporary production. Or something like that.]

In 2000, Shorter brought together pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci and drummer Brian Blade to form his last great band, a quartet that seemed to be built for spontaneous exploration. A fiery live group, the quartet only released five albums during their 18 or so years together, but established themselves as a singular unit based on mutual trust in flights of improvisation. The younger musicians seemed to bring out the best in Shorter as saxophonist and bandleader, while the same could be said of his impact on them.

In an interview with the group by Renee Rosnes (herself an alum of Shorter’s bands) at the Detroit Jazz Festival in 2012 and published in JazzTimes, the four talked about the unique approach of the band. “[With Wayne,] we submit to each other in this way that can build a community,” Blade told Rosnes. “You have to look to your neighbor; you have to look around you. These men are all about that. When I look across the stage, there’s a heightened sense of submission to that moment and to the potential to see that collective effort rise above your imagination. So I think that hopefully we all want that from life. We have such love and reverence for Wayne, just for who he is. You look at the writing, his creative gift. For me it’s just perfect. We can just play [the written music] from measure zero to one hundred, but he doesn’t want that! He’s like, ‘Let’s just get away.’ It’s interesting that he trusts us that much to say, ‘Let’s create something together, right now, with no script. Take a chance.’”

Bassist Patitucci reinforced the impact of that open approach to performance. “I think for me, and for all of us, that was so freeing-to be working with somebody who wrote such genius music who wasn’t captive to what he wrote,” added Patitucci. “He had a light touch on it; it didn’t hold him hostage. So when we played, he was talking about ‘Let’s get back to the place, but let’s play like we don’t even know how to. Let’s be that bold.’ …like a child. Like we’re discovering for the first time that sense of wonder. Whenever I would come home [from a tour with Wayne]-and this was early on, I’ve known Wayne since 1986-I would hear the melodies from his tunes that we had played. They would stay in my head for days and days and days. And it was that kind of thing, like when you first hear music when you’re really young and you get excited about it. It’s reclaiming that.”

“[It was like I] got enrolled in this galactic master’s program,” said Perez. “I see now, when I look back in my life, that it didn’t only help me with music but actually made a huge change in my life as a human being.” For his part, Shorter told Rosnes that the spontaneity in live performances started with the set list or the lack thereof. “No, there’s no set list we go by,” he explained. “We joke about, you know, let’s run over the music, but this is what that [phrase] means to me: We throw the music on the floor and we run over it!.”

During the conversation in Detroit, Rosnes told the four a story from back in the '80s about Shorter inviting her and the members of his new band over to his house to watch a movie as part of their introduction to his music. It turned out to be Alien. As the young bandmembers are watching the film and trying to figure out what it had to do with playing jazz with Shorter, when the movie got to the part where [spoiler alert] the alien suddenly pops out of the character (played by John Hurt) Kane’s stomach, Shorter grabbed the remote, paused the video and said excitably, “That’s what I want our band to sound like!" Point taken.

Recently in 2021, Shorter collaborated with bassist Esperanza Spalding on a project that had been on his mind for some time – an opera entitled Iphigenia, roughly based on Euripides' Greek tragedy Iphigenia at Aulis– which eventually premiered at Cutler Majestic Theatre in Boston, followed by performances at the Kennedy Center and other performing arts centers.

During his long career spanning many eras of jazz, Shorter received his fair share of honors, including winning 13 Grammy awards, being named an NEA Jazz Master, and having the street in front of WBGO in Newark renamed Wayne Shorter Way.

All of the above accomplishments and events don’t really capture Shorter’s distinctive personality which was as singular as his sound, combining a droll wit with the wry wisdom of an elder always in the warmest of tones, while never losing his childlike view of the world. His deep fascination for science fiction and tales of outer space would find its way into his conversations as well as into the music itself. Like most jazz veterans, Shorter liked to tell stories about his former bandleader Miles Davis, imitating that distinctive raspy voice. In turn, Shorter’s friends and colleagues would tell “Wayne” stories, albeit in their mentor’s sometimes stammering and hopscotch style of speech that often echoed his phrasing on his horn.

Terri Lyne Carrington not only played in Shorter’s groups in the ‘80s but would return to play with him, bassist Esperanza Spalding and pianist Leo Genovese in a performance at the Detroit Jazz Festival in 2017 that was later released on Candid and was nominated for a Grammy. In a statement released by Berklee College of Music, Carrington said: "The world has lost a great man and a genius musician. I’ve lost a mentor and one of my greatest inspirations. It so happens that this is on the day that I play Carnegie Hall for the first time as a band leader, so we will celebrate Wayne tonight, and always. Although I am extremely sad, and feel that a part of me has gone as well, I know that a part of him will always be with me. I feel incredible joy that I had the opportunity to learn from him, know him closely and most importantly that I got to share time on earth with such an amazing human being. He will always be with us - his gifts and light will continue to bless us all infinitely. In reflection, no matter how you try to prepare yourself, the mysteries of life and death unfold, revealing greater meaning and purpose to life itself. As Wayne himself said, his spirit is indomitable and with that I rest in knowing his mission continues in another form and through all of us that knew him, and even those that didn’t. The love for Wayne from his family, friends and the community at large is interminable and if we are lucky we can see ourselves as a reflection in his mirror, as he truly knew of things greater than most can imagine. The adventure continues, as his eternal life is for certain. But for now, may his spirit soar in all space and time."

#WayneShorterWay

#WBGO

#WayneSuperNova

#Wayningmoments