In my previous installment of Deep Dive, I discussed my personal history with A Love Supreme, and examined John Coltrane’s own planning notes for the suite. I should add, in response to some questions, that I had heard the piece many times before that day in 1978 when I suddenly understood the last movement and decided to write about it.

One curious thing I noticed in ‘78 is that there’s a second saxophone at the very end of “Psalm.” Later on, Victor Lin, an excellent pianist and violinist who took one of my Rutgers seminars when he was a grad student, pointed out that there are also two basses (bowed and plucked bass at the same time) and overdubbed drums (two-handed rolls on timpani drums, along with cymbal crashes and other drum sounds).

In September 1995 (or possibly ’96), while writing my book, I decided to see if I could find more information about the use of overdubbing, an unknown fact about this well-known album. I phoned Bob Thiele, the producer of this and most of Coltrane’s albums for Impulse. He was known to be a bit of a gruff personality. Sure enough, he said: “Are you crazy? Millions of people have heard that album. Don’t you think someone would have noticed if there is overdubbing on it?”

I held my ground, telling him that there certainly was overdubbing, whether or not anyone had noticed. Finally he suggested that I call Rudy Van Gelder, the recording engineer. I had already visited Van Gelder’s famous studio in Englewood Cliffs, N.J., with my friend Yasuhiro “Fuji” Fujioka, a Coltrane researcher from Japan, so we’d been introduced. But Van Gelder, also a cantankerous sort, had almost the same reaction in almost the same words. (“Are you crazy?!”) Again I refused to back down, and finally he said, “OK, I’ll listen again and get back to you.” It seemed a little strange to me that he would need to hear his most famous recording again to know if there was overdubbing! I didn’t hear back from him, so it went out of my mind.

Four months later, on Martin Luther King’s birthday, my phone rang. It was Rudy, whom I had given up on by that point. “It took me a while,” he said, “but I listened again to the end of ‘A Love Supreme’ and you’re right, we did do some overdubbing.” In fact, he proudly told me, he’d been a pioneer of overdubbing in jazz. Among some of his first recordings, he mentioned that back in 1954 he had recorded an album called https://youtu.be/Cbm3vQZ2cSs">Bobby Sherwood and his All-Bobby Sherwood Orchestra, where that swing bandleader played every instrument of a big band except saxophones. Now that he’d remembered it, from that day on Van Gelder mentioned the overdubbing when interviewed about the album.

Still, strangely, the added saxophone — who simply plays two notes an octave apart — sounds rather raw, not really like Coltrane. So after hearing back from Van Gelder, I phoned Archie Shepp, since he performed on the second day of recording. (In addition, photos now confirm that no other saxophonist was present.) But Shepp knew nothing about it, adding (I paraphrase): “I certainly think I would have known if I was on the most famous jazz album of all time.”

However, in 2005, Barry Kernfeld, editor of the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, was hired to listen closely to some of the Coltrane family’s tapes and make a detailed report of their contents. In the report, he mentioned that the second sax was dubbed at the end of the first day of recording, Dec. 9, and that it appeared to be Trane. (Via this link, scroll down to “John Coltrane in Rudy Van Gelder’s Studio.”)

My friend Ken Druker, vice president for jazz development at Verve Label Group, was kind enough to allow me to hear that overdub insert, which was not included on the released album because it contains no new material. (It’s identical to the last two minutes of the released, overdubbed version of “Psalm.”) He told me that the tape box says Dec. 9, so it has to be Coltrane (i.e., Shepp was not there). With that in mind, I listened again, and while it sounds rough — and the upper note, which is held out, has a rather unsteady vibrato — it certainly is identifiable as Coltrane. (Keep in mind that this came at the end of a long day of recording.) In fact, and perhaps significantly, it’s very similar to the two Cs that he plays at 22 seconds into “Psalm” (at the word “Peace,” if you follow the poem, as I’ll explain).

Coltrane added these two notes after the bass and drums had already been overdubbed. Since all this happened on Dec. 9, that also confirms that both bass parts (bowing and plucked) were overdubbed by Jimmy Garrison (because Art Davis was not there). And of course, both drum parts (rolls on the timpani, plus cymbals) were overdubbed by Jones.

Thanks to the complete set of A Love Supreme, we can now compare the two endings of “Psalm,” with and without overdubs — the released Master Take, which was the overdubbed version, is CD 1, track 4 (the same one in mono is track 6); the original version before overdubbing is CD 2, track 5. Listen to both, from about 6:20 to the end, to compare. Notice that there are no cymbals at the end of the original version, and only bowed bass (not plucked). And of course, there’s no sign of the second saxophone.

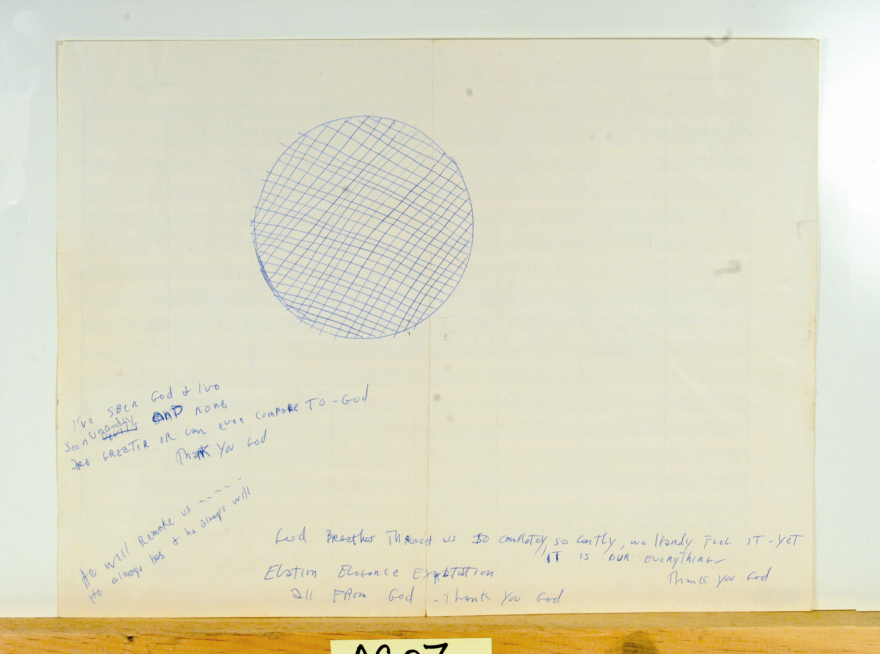

Now, going back to Coltrane’s planning notes for the album, the remaining pages do not have as much on them as the main page that we analyzed last time. Certainly, the most significant one is now labeled (not by Coltrane, but by the auction house) Ac07v3. (All of his note pages also appear in the booklet to the 3-CD edition.)

As you may recall, it appears that he did not originally plan for “Resolution” to be part of the suite. But six lines from the bottom, at the words “Melody Tenor,” this page shows the melody of “Resolution,” no longer in Bb as he played it before the recording session, but now starting on the note F. That must be the tenor saxophone part, which would translate to a concert key of Eb, which indeed is the key of the recording. And this page of notes has the title “A Love Supreme,” which confirms that at this point “Resolution” was part of the suite.

Notice that there’s a first and second ending. Although it’s an eight-bar theme, Coltrane always plays it three times, with a different, inconclusive ending the second time — so the theme is really 24 bars long. He writes “Approx[imate]” for the second ending, which in this case seems to mean “something like that.” His sketch resolves on the tonic, so it’s possible that he initially envisioned only playing it twice each time. But what he actually recorded at the second theme statement ends on the fourth of the key (Ab concert, Bb for tenor sax), leaving us in suspense and preparing for the third statement.

So, we now have “Resolution,” and in the key of concert F. But on this page the “Acknowledgement” sax part, marked “Tenor” in the middle of the page, starts on the note F, which is still the concert key of Eb. This confirmed by what he writes:

“Start and end in Eb concert minor.” So this isn’t yet the final version, which was in the key of concert F.

What follows is one of the most interesting passages in all of Coltrane’s notes for the suite: He sets the Main Motif starting on F, then on D, then adds “ETC.” Then he writes “Other instrument,” followed by the Main Motif starting on G, then on D.

And he writes:

“Move in all 12 keys” Then below that, “Move freely in 12 keys” — and at the bottom of the page, “Solo in all keys.”

I mentioned last time that there is a passage at the end of his solo in Part One where he takes the Main Motif and transposes it around, eventually going through all 12 keys. Really this passage is after the end of his solo. In every version of “Acknowledgement,” he essentially finishes his solo, and then begins repeating the Main Motif in various keys. I believe that this is his way of saying “‘A Love Supreme’ is everywhere.” And the fact that he explicitly planned to do that is telling.

On this page there’s also a “rythmn” [sic] that’s a little hard to place but could be seen as a variation on the Main Motif.

So, his original key and movement scheme, as described last time, was:

1. Intro in E, then Acknowledgement in Eb minor.

2. Pursuance, blues in Bb minor

3. Bass solo, free and open, after a very slight pause, connects with:

4. Psalm in C minor.

The final key and movement scheme, as recorded, is:

1. Intro in E, Acknowledgement in F minor. At the end, after the chant descends to Eb, there is a short bass solo.

2. Another short bass solo leads into Resolution in Eb minor (transposed from its original key of Bb minor).

3. A drum solo leading into Pursuance, blues in Bb minor. Then a bass solo, free and open, connects with:

4. Psalm in C minor.

Varun Chandrasekhar, who has just received his Masters in Music from the Univ. of Minnesota, has made a study of the key schemes and themes, and he feels that the final sequence of keys makes for a very coherent album and works beautifully with the various iterations of the Main Motif. He notes that on a practical level, it’s clear that Coltrane changed “Resolution” to Eb so there wouldn't be two up-tempo swing tunes in Bb minor in a row. But, he adds, at another level the change from Bb to Eb makes structural sense, which he explains in a theoretical analysis too detailed to summarize here.

Looking now at Coltrane’s other note pages, there is the one labeled Ac07v2, which contains a doodle and some lines from the poem. On the left, he writes “I’ve seen God and I’ve seen devils,” then crosses off the last word and writes instead “unGodly,” as it appears on the album.

The one labeled Ac07v4 contains a draft of the first third of the poem, just about in its final form. It reads from the top left (“I will do all I can”), down across to the right side. Up to “No matter what..it is God,” this exactly matches his final handwritten version (we’ll look at that), except that he writes at one point “Thank God!” instead of “Thank you God,” and he has added this in the margin, which is not in the finished poem: “We are nothing without you O God, [but] everything with you.”

Next, the line “He is gracious & merciful,” is omitted, but from there on it again matches the finished poem. After the words “I know thee,” he starts to run out of space, so he writes from left to right all across the bottom, from “Words, sounds,” ending with “Thank you God.” This page also has a sketch with the following annotations, expressing some of his philosophical beliefs:

Avenues of awareness

God’s index file

Dimensions

Containing All

He writes “Words” on one side of the sketch, and “Man” on the other.

Finally, he uses this page for two practical notes: a phone number near the bottom, and, near the top, a note to himself to “Buy reeds in SF” for his saxophone!

Then, there is the page AC07v5: This sheet presents three sketches of music, none of which seems familiar. At the top, apparently in pencil, are some chord names and whole notes that do not comprise a familiar theme. Perhaps he was working on a new idea for the second movement before he decided on “Resolution”? We don’t know. Under that, in pen, is another chord progression, with no melody. Again, it doesn’t match any piece that I can think of. Below that he's written this outline: Bm: 16 bars, Bb7+9: 8 bars, Bm: 8 bars. It's a simple outline for a modal AABA piece, but not a known one.

It occurred to me that maybe these weren’t all by Coltrane, but the handwriting does appear to be consistently his. I wonder if he was writing these out for somebody else? They almost look like suggestions for a student to try out. Or, for that matter, suggestions to John from his own teacher, the late Dennis Sandole.

The words at the bottom are a draft of the acknowledgements for the album, including reminders to himself such as “thank [sic] to Shepp and Davis (& apologies if necessary),” referring to the phrase that he later added, that their recorded contributions “regrettably will not be released at this time.”

Among other passages that we recognize from the published notes, he works on this line: …“in the bank of life Isn’t good that investment which (written over “that,” I think) surely pays (over “brings”) us the highest and most cherished dividends (“peace of mind?,” crossed off).

AC07v6 is a longer draft of his liner notes — probably an earlier one, because it is quite a bit different from the final version. Some of the same ideas are there but expressed very differently. For example, he writes: “Through the help & grace of God I was enabled several years ago to throw off shackles that had bound in many ways and stand in the pure light of his love…” Compare that with this from the album notes: “During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life.”

Further down the page, he writes, “We will strive to give more (“do better” is crossed off) in our future works if it be his will that we are to remain here a while longer.” It’s ironic and sad that Coltrane was only to live about another year and a half, but let’s not read too much into this. It’s a fairly standard religious sentiment, and by all accounts he didn’t feel seriously ill until very near his death in July 1967. This is not an indication that he knew his time was short.

At the bottom he reminds himself to include a “Short discourse on music in album through prayer [sic] include words of prayer.” As we will see, the last movement, “Psalm,” is a reading of those words of prayer, so perhaps that’s what he’s referring to here.

There is yet another draft of the album notes that is much closer to the final version. Here he refers to Part IV as a “Hymn on [the] prayer” (near the bottom of the page).

Now that we’ve examined what Coltrane had planned, let’s complete this second Deep Dive into A Love Supreme by studying what actually happens in the recorded performances of the first movement.

First of all, please note that the first movement is called “Acknowledgement,” not “A Love Supreme,” as it is sometimes announced in concert. Second, the bass only plays the Main Motif a few times at the beginning, then moves on. I’ve seen performances by professional as well as student groups where the bassist plays the ostinato throughout. It gets very tiresome, but more important, it’s contrary to Coltrane’s intention. In fact, since this movement is really a fairly loose improvisation in F, with almost nothing pre-planned except the key, the rhythmic approach (“feel”), and an outline of the sax part — and the latter is only in Coltrane’s mind, as we’ll discuss next time — one could argue that it makes no sense to try and “recreate” it at all.

If Garrison does not simply repeat the Main Motif, what in fact does the bassist play? The common “wisdom” is that in the Coltrane quartet, Garrison held down the beat so that Elvin Jones was free to do whatever he wanted. In point of fact, that is not what one hears on most of the recordings. To be sure, in Nov. 1961 — on “Chasin’ the Trane,” the first released recording of Garrison with Coltrane — he keeps a strong walking beat on the bass. But when Jimmy officially replaced Reggie Workman at the end of 1961 and started to work regularly with Elvin, he soon loosened up and began breaking up the beat. After all, don’t forget that he came to Coltrane after working with the Bill Evans Trio (in 1958 and ‘59, just before Evans enlisted LaFaro; this group is documented on recordings with clarinetist Tony Scott) and, earlier in 1961, with Ornette Coleman. That’s two of the most interactive groups in jazz!

It’s nice to hear Lakeisha Benjamin’s https://youtu.be/DUqse5tklkk">recent version of “Acknowledgement,” on her album Pursuance: The Coltranes (the plural refers to Alice as well as John). The rhythm section sets up a different groove than Coltrane’s, and bassist Jonathan Michel takes a very active role (not just repeating the Motif).

Listen now to the Master Take (the released version) of “Acknowledgement,” and focus on Jimmy Garrison’s playing. From the moment Coltrane begins his sax solo, at 1:03, Garrison stops repeating the motive and plays freely.

Let’s also study the takes of “Acknowledgement” that were recorded on Dec. 10 with two bassists, Garrison and Art Davis. Here are my own rough notes, taken while listening:

Take 1 (CD 2, track 6):

Strummed basses at beginning.

Then both bassists with the Main Motif.

Trane solo starting about 1:50. Then Shepp, and Trane returns around 3:20.

From 2:15 on, the basses play freely.

Instead of a short bass solo at the end of part one, both bassists solo together at 7:15. At first, it’s Garrison who is playing the Main Motif, and Davis who is soloing freely. Then from about 8:30 onward, Garrison improvises.

Take 2 (CD 2, track 7):

Both strum; then one bass, then both, come in with the Main Motif.

Trane solo starts at 1:35

Then Shepp is featured at length.

In this one the bassists play the ostinato all the way to around 5:15, after which they improvise. Both basses solo from about 800ff. Again, Davis solos first. There’s just a bit of Garrison’s double stops (two bass notes at once) before this take ends.

Take 3 (CD 2, track 8):

A little discussion with Davis about “to play that high” on the bass. Then a “false start,” that is, a take that is cut short, in this case because the basses do not seem to be in sync with each other. (Kernfeld says it appears that Davis wasn’t sure where “one” was.) Coltrane says “Alright — go again.” But first there is a short discussion, from which we learn that after the opening fanfare, Coltrane was giving Elvin a “count off” with his hand, like a conductor, to start with solo drums. It’s hard to hear, but this is what I make of the conversation:

Davis says, “Oh, you’re counting 4 for one” (four beats for one bar).

Coltrane, overlapping, says “I’m giving him (Elvin), 1,2 — just one bar — 3,4.”

Davis replies, “Oh, that’s a slow four…?” Coltrane says, “No,” followed by something that overlaps Davis. Davis says, probably indicating Jimmy, but possibly Elvin: “Yeah you, you, you turned it (the beat) around then, you turned it around, because I think…” Coltrane interrupts, saying “No, I want to give him, I’m giving him a four-beat pickup,” and then John counts off twice as fast, “1,2,3,4,1 — like that.”

Davis says something about a “long count,” and John says something about “Yes, but I didn’t mean that — shorter.” “Okay,” says Davis.

TAKE 4 (CD 2, track 9):

Clearly, there was more conversation after Take 3 that was not recorded. Because from here on, the bassists play much more freely, only referring now and then to the Main Motif. Also, Davis bows the note E at the beginning while Garrison strums. On this take the basses start with a variation of the Main Motif, playing the Main Motif a few times between the 1- and 2-minute mark, but mainly, they continue to play fairly freely, and then they solo around 7:00, Davis first as before, then Garrison.

At the end Coltrane says, “Let’s hear it.” (That is, let’s take a break and listen to the recording of that take.) Then he adds something about, “I think we’ll do one more and get ‘em.” (That is, we’ll get a satisfactory take).

Take 5 (CD 2, track 11) is a very short false start. It sounds like Davis was not quite ready, and didn’t have his bow out.

Take 6 (CD 2, track 12):

On this, the final take and the longest of all, the basses play very much as they do on Take 4, except that they repeat their variation on the Main Motif for quite a while before moving into other areas.

Art Davis, a brilliant man and a brilliant musician, liked to say that he was Coltrane’s favorite bassist. He had toured with Max Roach (starting in 1958), and then with Dizzy Gillespie.

Coltrane told British journalist Val Wilmer: “I actually wanted Art to join me as a regular bassist, but he was all tied up with Dizzy, and so I had to get in Steve Davis.” This would have been in the spring of 1960. Steve, unrelated to Art, was one of John’s many Philadelphia colleagues. John continued that when Steve left around the beginning of 1961, “Art still couldn’t make it, so I got Reggie [Workman].” Davis had just left Gillespie upon returning from a tour of Europe (he was replaced by Bob Cunningham), but he turned Coltrane’s invitation down because he had decided that he was done touring. He was doing well freelancing in the New York area, where he lived with his family, especially in commercial recording for TV and radio.

Coltrane told Wilmer that he invited Art to come to a New York gig “because I liked him so much and I figured that he and Reggie could exchange sets. But instead of that they started playing some together…and it was very good.” So for much of 1961, Davis played a number of Coltrane engagements with Reggie Workman also on bass, and sometimes Eric Dolphy as well, making the group a sextet. These were mostly in New York City but possibly also in Philadelphia. But when Coltrane went to California in Sept. 1961, Davis did not go along. And at The Village Vanguard in the first week of November, Coltrane tried out Jimmy Garrison on some numbers, even though Workman was still in the group. Workman was already committed to play on John’s European tour right after they finished at the Vanguard, but soon after they returned, Garrison took his place.

Davis held fast to his decision not to tour. His discography shows that he only recorded in the New York metro area (with one excursion to Syracuse, N.Y.) for the rest of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Still, it seems ironic that Davis, to his dying day, insisted that he was overlooked by Coltrane fans. If he had agreed to be the regular bassist in the quartet, of course he’d be famous and celebrated today. But he wanted to have his cake and eat it too — to reject the offer to tour with Coltrane, but to still enjoy the reputation of being Coltrane’s favorite bassist.

It didn’t work out that way. But his playing when he recorded with Coltrane in the New York area was always stellar — on Africa/Brass, Olé, the Dec. 10 takes of “Acknowledgement,” The John Coltrane Quartet Plays, and, finally, on Ascension.

Let’s pause here for now. In the third and final installment of this Deep Dive into A Love Supreme, I’ll talk about these topics and more:

Coltrane’s saxophone solo on “Acknowledgement.”

“Reading” the poem on the saxophone in “Psalm.”

Other pieces where Coltrane reads a poem on sax (not the ones you might think!)

Two “live” recordings of A Love Supreme (yes, I said “two”).

Don’t miss it! And in the meantime, stay safe and be well!