We can’t gather in person right now, but we can still be together.

WBGO’s Fall 2020 Jazz-a-thon flows out of that conviction, with a nod to the past and an eye on the future. Featuring exclusive performances from our archives, it will evoke the joyous, determined feeling of our old round-the-clock fundraising blitz, which fostered a listening community and helped put WBGO on the map.

The first Jazzathon was a 24-hour affair at Fat Tuesday’s, on Dec. 13, 1982. The following year, having passed the proof-of-concept phase, the Jazz-a-thon received glowing preview coverage in the New York Times. It featured everyone from Dexter Gordon to Dakota Staton, along with the first public performance by Sphere, the Thelonious Monk repertory band.

In later years, the Jazz-a-thon moved to rooms like Greene Street Café and The Village Gate, paring down to a shorter shift. But the atmosphere was always the same, as musicians and fans came together in celebration of the music, and in support of WBGO. We need that spirit again now, as we head into an uncertain fall. Please support us, so we can continue to bring you the best programming on the air and online, and keep serving the music.

To kick off this virtual celebration, our editorial director, Nate Chinen, called up WBGO’s cofounders Bob Ottenhoff and Dorthaan Kirk, to talk about legendary Jazz-a-thons past, and why it made sense to bring the idea back again this year.

Well, it’s appropriate to be speaking by phone today rather than a Zoom, because we’re talking about a time when all of your calls would be made from a landline. And I’m sure that, putting together the Jazz-a-thon, there were always a lot of calls made.

Dorthaan Kirk: Right!

Bob Ottenhoff: Just imagine coming back into your office and seeing 20 pink slips of various phone messages. I still have one framed over my desk. It was from Greene Street [Café], and all the phone message said was: “URGENT.” [laughs]

DK: I remember that.

And what was that urgent message?

BO: Greene Street is a restaurant and bar, in a wonderful location in SoHo. And the proprietor there, Tony Goldman, generously offered the facility as our site. Unbeknownst to us, Tony was already on shaky ground with his neighbors, who complained about crowds of people and the noise, and so forth. And when they heard that we were doing a Jazz-a-thon in his place, they called the police and the cabaret officials and said they were going to shut it down. So the urgent message came about eight hours before the Jazz-a-thon was to begin. There were complaints about potential noise, so we had to scramble to make sure we could still hold the event. We ended up building a compartment, a little box out of plywood. And the drummer had to sit in that little spot for the whole night. We also had to keep someone at the door to make sure the cops weren’t going to come in and shut us down.

How did the Jazz-a-thon first come about?

BO: There were two ideas on my mind. One is, imagine starting a brand-new radio station in the New York metropolitan area, with a hundred radio stations already existing. No marketing budget, no promotion budget, no advertising. All we could do is go on the air. And so an early goal was to increase our visibility by being part of the jazz scene, wherever it was happening. So we started doing live concerts from Tower Records in Lower Manhattan. We started doing concerts in Military Park, across the street from WBGO. Wherever there was jazz, we wanted to be part of it.

Right.

BO: The second part of it was, we wanted to build a sense of community. We wanted people to feel like they were part of WBGO. We’re a community of lovers of music. And as we thought about the characteristics of being a community, one thing that came to mind was the tradition of rent parties, where people would volunteer their time, and musicians would come, and people might bring a potluck dinner. They might bring up their own drinks, but it was a sense of community that was helping that person pay the rent. In the case of Jazz-a-thon, it was musicians donating their time. And then we broadcast these live, so if you couldn’t come, you could at least listen to it and make a pledge on the air. We were building the sense of a community of jazz lovers all pitching in to do their part to make the station work.

In the coverage of those early Jazz-a-thons, one point that’s often made is that musicians were among WBGO’s most loyal listeners. That’s directly relevant to that point about community, right?

BO: I think that’s right. And there was definitely a lot of dialogue going on between the announcers and the musicians. So Dorthaan’s job in all of this was to be our ambassador, our diplomat who could reach out to people, and do it in a graceful way. Only Dorthaan could call to say, “Hey, I know you’re a busy guy, but would you mind coming down to Fat Tuesday’s at 11 o’clock on a Saturday night, and giving an hour’s worth of your time, at no charge?

Was it a challenge to make those calls?

DK: I think it was fairly easy, because the musicians who had what you might call “name value” back then, they were quite different than the musicians with name value are today. Back then, the musicians kind of made his or her own decisions. Some of them had managers / agents, but for the most part, they wanted to be a part of it, even though they already were famous, because they wanted the publicity and wanted to be involved. And remember, WBGO was the place that their music was getting played. Remember that after 1980, there was no WRVR. So it was a win-win for everybody.

BO: It was a different music scene in those days. You know, we hear stories about what it was like in the ‘40s and ‘50s. But some of that still existed in the ‘80s, so that there were a number of clubs. There were, on any given night, quite a few musicians in town. So you could stop by for an hour, or you could hang out for a couple of hours, because there was still a pretty vibrant music scene going on, much more so than exists today.

Do you remember any memorable encounters as you were inviting musicians, and in some cases, twisting someone’s arm to make an unusual hit?

DK: The first name that comes to mind is Big Joe Turner. In order for him to perform, they had to carry him down the steps in a wheelchair. The Village Gate had a space upstairs, then there was a bar on the side. And then there was the space downstairs. And I think that’s one of the most ridiculous things that we did that really, really worked back then. I remember the room was really, really packed. That stands out in my mind.

BO: I remember the stairs going down to Fat Tuesday’s, and that was a challenge. That was a small space as well.

DK: I believe the capacity downstairs at Fat Tuesday’s was something like 90 or 100. And it had a long hallway where you lined up. Then you went down the stair. Once you were down there, unless you really knew the exit, it was one way in and one way out. However, us being involved, we were able to find where there were other exits that the general public didn’t know about. You remember that, Bob?

BO: I do. It was something down there. You know, another thing that strikes me is, there was so much energy. People were so excited. The community was so excited. There was fabulous music. But I’m not sure the economics worked out all that well. We tried to also do fundraising on the air, and my memory of that is that the music was so good that it was hard to get people to pledge. Because they were listening so much.

It’s worth noting what a broad range of style there was on the lineups. Taking 1983 as our example, there’s the aforementioned Big Joe Turner. Abbey Lincoln was also on the bill. There was a Jimmy Cobb project. But there was also Gil Evans, and the David Murray Quartet, and George Adams with Don Pullen. There was some fairly avant-garde stuff in there, and then stuff that was more groove-oriented, and stuff that was really swinging. So what was your approach to the curation?

DK: We wanted to present a wide range of artists to represent what we were playing on the radio. That’s how I remember it. But while I have the floor, I want to go back to Fat Tuesday’s. If you remember, Bob, at Fat Tuesday’s we did four-hour blocks of time because it was so small. For ten dollars you could stay four hours, and I assume Fat Tuesday's imposed a one or two-drink minimum. So we turned the house over every four hours, and the thing that fascinated me was, we had a line of people waiting to get in early Sunday morning, ‘cause we kicked off at midnight with Clark Terry, who was the artist performing there that week. I remember leaving sometime early in the morning, going up to my friend’s place at Central Park, west of 100, to get a nap and change my clothes. We only had a handful of people to do all this work. That first one still stands out in my mind.

BO: Is that the only one we did that was 24 hours? Did we decide after that one, we couldn't handle 24 anymore?

DK: I believe that’s the case, Bob.

BO: Because I looked at some of the later ones, and they were always 12 hours or 18 hours. But 24 hours was tough — and I’m sure not only for us, but there were a lot of people who stayed for the whole 24 hours.

This was a major WBGO event in Lower Manhattan, and I wondered: was there ever discussion about holding the Jazz-a-thon, or some part of it, in Newark?

BO: Well, for one thing, we were doing a lot of events in Newark anyway. I mentioned the concerts in Military Park. There were still a few clubs at that time, too. Remember Sparky J’s? We did a few concerts there, and in other places. So that was one: we were already doing a lot in Newark. And the second thing was an issue we talked about a minute ago: we needed to be in a place where there were a lot of musicians that night who could stop by. So it was a concentration issue.

The Jazz-a-thon was typically held around the same time as the KOOL Jazz Festival. Was that ever a challenge, competing with what was then the flagship fest in town?

BO: I think we were kind of riding on their coattails in a way, weren’t we? Didn’t that help with that concentration-of-musicians issue? There were a lot of people in town. there were tons of partners

DK: I think because of the low fee for Jazz-a-thon, as opposed to whatever else was going on, there were tons of people who came to ours because of that. And another thing: back then, unlike now, there were tons of artists that were household names. People knew everybody. Nobody hardly knows the artists out there now. So they could see all these masters for a little bit of money.

BO: And personally mix with them. Because it was a very informal environment. But I wanted to get back to something you mentioned about the range of musicians. And I think WBGO was new enough then that certainly inside the station, there was always lots of debate about what to play and not to play. Al Pryor, who was our first program director, was part philosopher. Wouldn’t you say so, Dorthaan?

DK: I would!

BO: He liked to talk about music history and music tradition, and we would have lots of debates about how we understand the trunk of the tree, and it’s OK to have branches — but how many branches can we have? And of course, listeners are always calling to give us their opinion about whether we’re playing too many dead musicians, or not enough young musicians, or vice-versa. There was a lot of debate about, well, what does it mean to be jazz? We wanted to be pretty flexible, pretty open. As long as it was connected to the trunk of the tree.

Why does it feel right to be reviving this idea of the Jazz-a-thon for a fall 2020 fund drive?

BO: It reminds us of a world that once was. And in some ways, a world that once was only six months ago — but also a world that once was 30 years ago. It’s a world that we can’t have right now. And so a part of what we’re trying to do is replicate, as best as we can, the excitement and the energy and the good feeling that happens when you’re in a live performance venue with your friends, and you get a chance to see this extraordinary talent. And it’s only 10 feet away from you. So we wanted to recreate that. But the other thing is, for me, it’s a way to reenergize that sense of community. In this time of pandemic, we are all, as lovers of jazz, still able to be with each other, to share music, to share good feelings, to share companionship. And we’re all in it together to make sure that it continues.

DK: Whenever the pandemic allows people to congregate again, I think people are going to have a new way of thinking about jazz and going out of their way to support it. Because they have been so denied of it. I think now people will make more of an effort, because they’ve seen how the pandemic has affected them from experiences that they could have had.

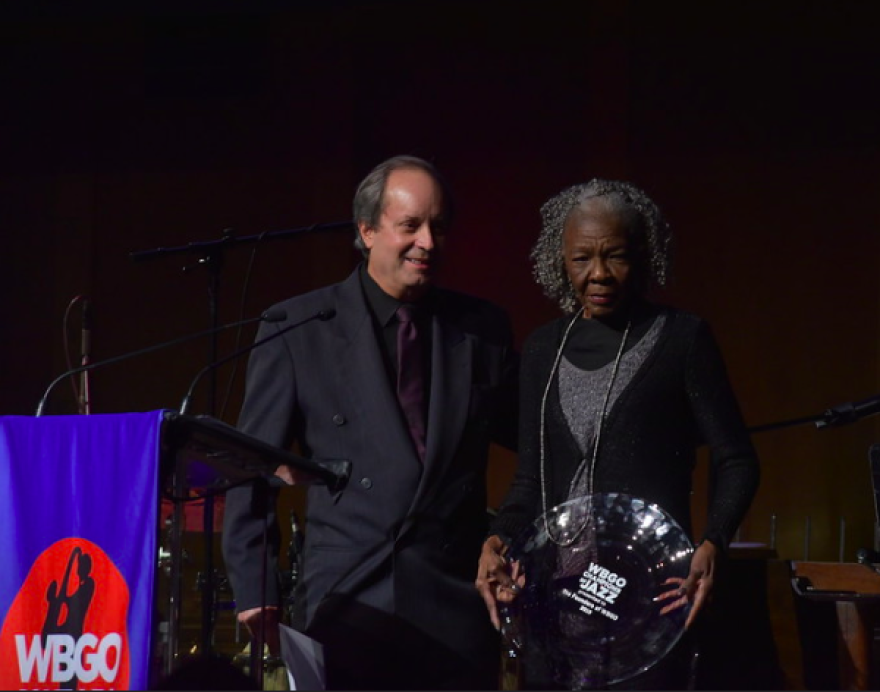

Bob, you’ve spent most of this year as interim CEO, back in the saddle at WBGO. And Dorthaan, we celebrated your induction as an NEA Jazz Master. I’m sure you have kept in touch over the years, but this year you were really brought together. What reflections do you both have about that?

DK: I have one thing to say. I think WBGO was simply meant to be, based on how it came about, all the challenges that it’s had over the years. And Lord knows, I was there for most of it. And having come full circle with Bob, as you just said, it’s one of those things in life that is very hard to explain. Because remember, Bob, way back when they were saying your idea of WBGO being a jazz station, it wouldn’t work. It couldn’t be done, blah, blah, blah. Here we are, 41 years later. That’s how I see it.

BO: I think Dorthaan just said it all, very well. All I can do is make it worse. [laughs] I think it was meant to be. It was magical. Dorthaan and I didn’t know each other, and we became not only fast friends but accomplished a lot together. And we were surrounded by hundreds of other people who wanted to do their part, who helped us out in big ways and small ways to build that sense of community. So it's a wonderful thing.

Are you both hopeful for the future of this organization?

BO: Every day I marvel at what our listeners have to say about WBGO, and how many of them say it has changed their lives, or they couldn't do without it, or how we teach them something new. Every day we’re getting love letters from listeners all over the world. I just hope that those who work at WBGO realize just what a treasure it is, and what a responsibility they have. I think sometimes it’s easy to think about ourselves rather than think of what it is we’re responsible for. And it’s our listeners who remind us every day just how powerful an idea it is, and what a difference we make in the lives of thousands of people.

Support WBGO with an online pledge during our Jazz-a-thon Fund Drive, or call us at 1-800-499-9246.