Cynthia Sayer is truly an anomaly in the jazz world and not because she’s a woman instrumentalist. Rather it’s the instrument itself that sets her apart from so many of her fellow jazz musicians. One of the foremost jazz banjoists in the world, Sayer recently won the prestigious Steve Martin Banjo Prize, which came with a hefty cash award as well. Sayer has been performing and recording her unique mix of traditional and modern jazz for more than three decades and is recognized as an authority on the instrument’s history and evolution. Beyond her career as a virtuoso on her instrument, she’s also the author of The Swinging Solos of Elmer Snowden, about the work of that underappreciated banjo player in jazz’s history. In addition to leading the band Joyride, Sayer has a show called The Banjo Experience, featuring a host of fellow banjoists and string players, which will be presented at Lincoln Center on March 29.

She talked with me about the award, her journey as a musician, and her mission to rid the instrument of its historical stereotypes around race and gender and to make the instrument more known for its unique sound and styles. She even explained the characteristics of her instrument and played a short number for us.

Listen to our conversation, above.

Interview transcript:

Lee Mergner: Was banjo your first musical instrument?

Cynthia Sayer: No, actually, I played various other instruments as a kid. Piano was my first love. I started that at age six and I also had a guitar. I took viola lessons in school. I played orchestral drums. At one point during our school talent show I saw our dance band. That's what they called it. I went home and told my parents I wanted a drum set and they were like, “No way.” We had this argument about it. Then I came home from school one day and there was a banjo on my bed. The minute I saw the banjo, I knew it was a bribe, and I wouldn't get my drums. So I thought, “Okay, I'll take it and try this thing.”

I grew up in New Jersey, not exactly the land of banjos. I had very little reference to what it even was. I had seen Hee Haw on TV. I kind of knew the bluegrass thing a little bit but it was not in any way in my world. Then I went to a lesson and it ended up that there was another woman who had moved to our town of Scotch Plains, New Jersey. At the time I didn't understand how completely rare this was, but she was a professional female banjoist at a time when there were no women. Not only that, I had never met a grown-up female in the arts.

I'm enough of an age that we didn't see these role models around us at all. I was so taken by her that I wanted to take banjo lessons so I could really hang out with her. She introduced me to the instrument and to the music. Her name was Patty Fisher. Eventually, I found my way into jazz. I have Patty to thank for introducing me to the banjo.

Was your first banjo a four-string, as you have now, or was it a five string?

Patty explained the three different kinds of banjos that we were most familiar with—tenor, plectrum and five-string. I play a plectrum banjo, which is the first cousin of the more popular five-string, which most people are familiar with. When people think of banjo, they mostly think immediately of five-string and bluegrass, country, old-time folk music and so on.

The plectrum banjo was the original fretted instrument of jazz. The four-string banjos evolved later when strumming started for a different kind of music that was starting to emerge. There was dancing and there was a different groove, a different rhythm. The guitar players in New Orleans switched to a four-string banjo in order to have gigs because their work was drying up otherwise. The four-string banjo was associated with a very different kind of music, which was evolving in the United States.

Patty was a plectrum player. She explained the difference to me. She said, “I can get you started on a five-string. I can get you started on tenor which is another four-string banjo, which is pitched and tuned just like a viola. But I can take you the furthest on plectrum.” Since I was 13, I said, “Okay, I'll play plectrum.” I didn't give it any thought at all.

I always liked tenor and plectrum pretty much the same. It was just circumstance that I played plectrum. Eventually, knock on wood, I came to prefer this tuning which has a tighter chord cluster sound. I am someone who likes being a person of today. I'm not trying to recreate the sounds of 1920, although I want to pay tribute to them. I like the more contemporary aspects that I can get out of this instrument.

The voicings on a tenor banjo end up with a more traditional impact to the ear, in my opinion. But I've heard some people who play that banjo perfectly well and don't make it sound so traditional. Clearly, it depends on the player. I like the tight chord clusters of this instrument. This is a very close first cousin to the five-string banjo that people know so well, it's just minus the fifth string and one note off of one of the five-string tunings.

In four-string banjo land, we have a tuning, and we play it, and that's it. I'm sadly ignorant about the five-string world. I understand five-string players have numerous tunings that they'll use and shift to depending on the piece and depending on how they want to use that fifth drone string.

That's not so we don't use capos. If you want to play in a different key, you play in a different key, so it's a very different mindset. One of the things that I would love to speak about here is how very different our worlds are and how little we know of each other, even today. During the Steve Martin Prize presentation after the show and live stream, we all chatted a little afterwards.

Just like drummers, you always have to talk about your hardware.

We were talking about how it was so interesting to hear some of the comments about our different styles. Honestly, I got some affirmation about how little five-string players still to this day know about four-string and vice versa, unless you play both.

Some people of course play both kinds of instruments and I don't separate tenor and plectrum so much, except in terms of tuning. There are pluses and minuses for what's a little harder and what's a little easier on the different instruments. There's the sound difference of the tighter tuning versus the tuning being in fifths and the broader tuning of a tenor.

In my mind, they are pretty much in this jazz category. They're in a similar category and you can make those musical choices as to how you want to play them. The five-string world was so foreign. It was like a trumpet versus a trombone. They're both brass instruments, but just because you play trumpet, doesn't mean you know how to play a trombone. There's a slide and there's a whole different way of playing. It’s the same thing with five-string and four-string banjos. There are other kinds of banjos too. Bass banjos, six-string banjos, piccolo banjos—there's a whole banjo family.

But let’s stick to the three main kinds that are out there today—tenor, plectrum, and five-string. One of my things is to try to make our worlds not so separate from each other. I've done programming at some Lincoln Center shows to this effect. Also, my personal musical choice is not to have the limitations. Actually, I don't want to call it a limitation but instead the musical preference of being traditionally focused.

I play whatever I feel like playing. For instance, one of the tunes I’m playing right now is a Linda Ronstadt tune that I like. I'm doing a jazzy version of it. I do tangos, I do classical music, I do whatever, but my eclectic programming is not only to show the range of my instrument and what anybody can do on a banjo. The other thing about banjos, as most of us know, is they historically were very narrowly stereotyped until someone like Bela Fleck came along and broadened our minds and broke down some of those barriers. He helped a lot of people, including me, and had a direct career impact, because it was so annoying to have these presumptions of what I could be hired for and what I could do. That was such a small part of what was possible. Anyway, I've tried to go wider and wider as the years go on and expand my repertoire and my musical influences.

I hire people in my bands who are multi-genre artists and sometimes just from other genres. They help me stretch and grow to all these new and different areas. To return to the five-string and four-string worlds, I don't know if I wasn't familiar with other four-string players who went out of their way to actually work with and share the stage with five-string players. I connected most to five-string players who play jazz such as Tony Trischka and Bela Fleck. We've worked together off and on over the years. It’s been a while since I've seen Bela.

There aren't that many.

There aren’t that many, but there are some. I get the impression that five-string players are a little more musically expansive and boundary breaking while four-string players tend to be a little more traditionally minded. I don't want to offend any of my four-string community out there, and I don't even know if that's entirely true.

Maybe there are new generations where that's less true now, but I've tried so hard to connect our worlds and it's actually not so easy to do it. This next program that I'm doing at Lincoln Center is called The Banjo Experience. Since I'm a four-string banjo player, I'm doing it from my perspective, which leans on that, but I'm involving every kind of banjo that I can.

I'm trying to create a banjo orchestra and have five-string and four-string, ukulele banjo and mandolin banjo and create all these things while also featuring some different styles of music. I'm sitting here in development of this program right now and trying to put us all together. It's challenging because we have such different mindsets about this music, but I love doing this. There's no reason for our worlds to be so very separate as I perceive that they are. They're a little less so, but we’ve got a long way to go.

One of the things you do is you play single note lines and bend notes. Wasn't the four-string much more of a chord-hitting kind of instrument to cut through the band sound?

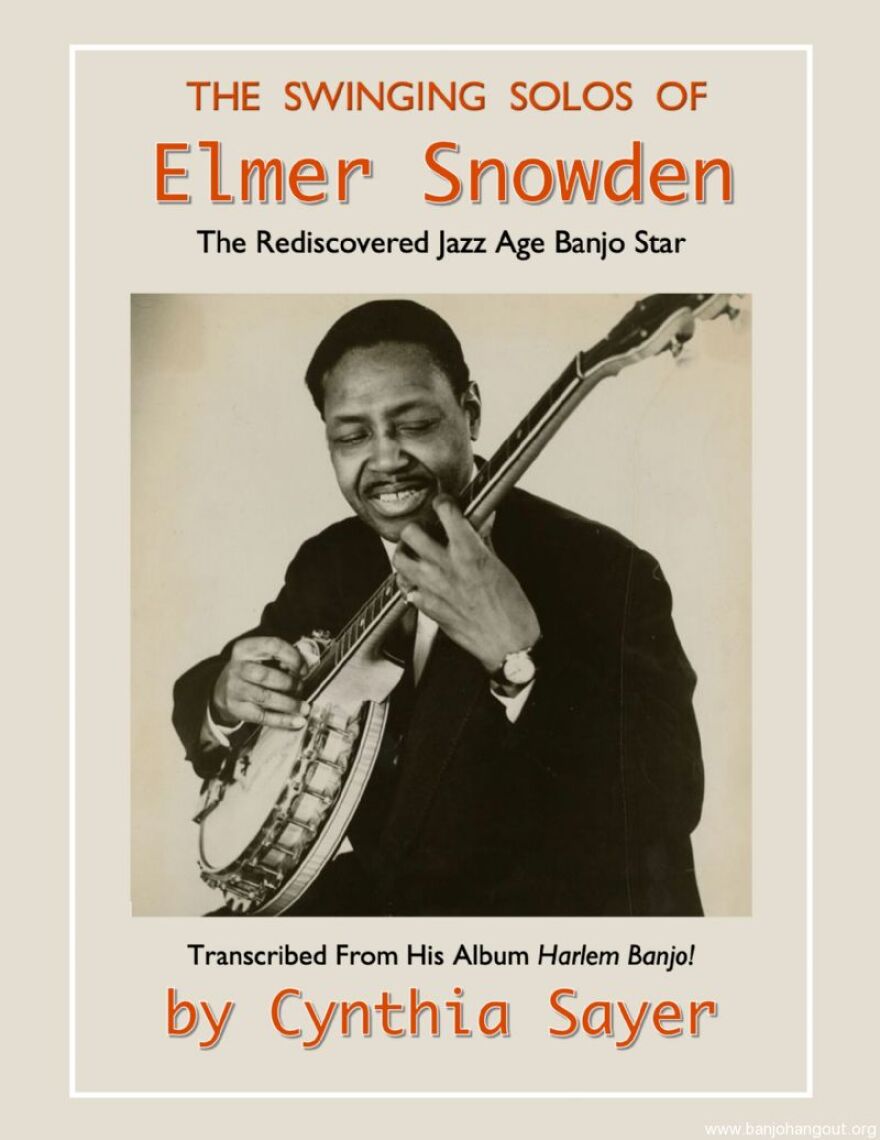

There are historic examples of great jazz banjo stars who did a lot of kick-ass swinging, single string work. Some of them were known for their very theatrical, virtuoso skills, and some of them were swinging. My banjo hero is an historic player named Elmer Snowden. If anyone wants to ask you about that, listen to that Harlem Banjo album.

It was so interesting to me that he was rediscovered the same time as Lonnie Johnson and both of them were in Philadelphia. Lonnie was working at the Bellevue, and Elmer was a parking lot attendant, right?

I think he was a parking lot attendant. This is all thanks to Chris Albertson, who I had the great honor of knowing and who became a friend when he learned that I was trying to get recognition for Elmer. The four-string banjo world wasn't even familiar with Elmer Snowden. Now he's known and they have things about him in the museum.

These people were forgotten. Chris found him and brought him back. He was a big star in the 1920s but he had some unfortunate business issues and eventually left New York. When guitar came back in fashion around 1934, musical taste evolves and changes, so he just left after a while. Many of today's recognizable leading jazz artists played in his groups in the 1920s.

Johnny St. Cyr, who worked with Louis Armstrong, is an example of a guy who was playing some swinging lines, but is also an example of a six-string banjo player who changed when the fad moved to four-string and everybody was doing that. He was like, “Well, hell, I know how to play guitar. That's too much work. I'm just going to put on a six-string neck.” He did that and it sounded great. There's a whole range of talent who did a lot of single-string work.

Harry Reeser was a big virtuoso who was all about his dazzling chops. He was a violin prodigy who decided to be more fun, I guess, and play banjo and switched over two years later. He's like a national phenomenon. One of the most famous banjo players historically was Eddie Peabody. My dad saw him perform, and he had this whole identity of banjo as very theatrical with a lot of showbiz flair associated with the four-string.

A lot of that comes from the banjo’s history of minstrel show, then vaudeville. There's a musical trajectory for all of these things that we hear today, including whether a player is male or female or white or not white. There's history to all of that.

I think one of the amazing things about the banjo that most people don't realize is that its roots were African. Because of the banjo’s association, for the most part, with minstrel music, country music and bluegrass, it's generally associated with whites. But in fact, it was originally an instrument that came from Africa.

Exactly. It was an instrument that came from Africa and also for many years was considered indeed an African instrument and that fact became part of its historic trajectory. Also, there was a time when the banjo was considered very low-brow and only for Black people.

It was like a whole thing. It was associated with slavery. It was associated with minstrel shows which gave it a very intense racial stigma. When I started playing, I didn't see any person of color [playing the instrument]. I can think of three people in the four-string banjo community who are not white. That's it, except in New Orleans. The one place I could go was to New Orleans where I could see people of color playing the banjo. That was it.

Of course, when I was 23, I didn't really think about it all that much during that period of time. But after a while, I was like, “I don't get it. Where are the women? Where are the African Americans playing this instrument?” The reasons for this gap are because of the very fraught social history of this instrument. I did a program on that called The Unexpected Journey of Jazz Banjo, where I delve into banjo history. There are some wonderful programs out there, that other banjo players do about banjo history, but they don't get into the four-string banjo.

The Carolina Chocolate Drops really did sort of revolutionize all that.

It's a different thing, but it's all a part of the same process where we are trying to unbury and acknowledge this instrument and this incredibly rich, fascinating but troubling and dramatic part that it played in American history. It's really intense, when you learn about it. When banjos started to be mass manufactured, there was a movement to get white people to play the banjo and to disassociate it from this African thing, because white people had all the money and that's who they were trying to sell to.

There were all these stories. Women, the African thing…it became a symbol of being daring and rebellious to play the banjo. If you were a female, if you were a society woman playing the banjo, that was really cool. In earlier times. if you were a woman, it was okay for women to play because women were considered simple and emotional like Black people. There was a whole social burden put on this instrument until myself and people like Rhiannon [Giddens] and the Chocolate Drops, and all of these artists who are out there now. They're bringing it all finally full circle. It's really a healing and a rich and wonderful musical movement about this instrument. But the four-string is still kind of left out. So that's my job.

That's on you.

Have you ever seen a banjo player included in a jazz book? Have you ever seen a banjo player included in a jazz documentary or a jazz program of any kind? They are completely absent. Again, there's historic reasons for this. Banjo is the original fretted instrument of jazz so you would think some of the main banjo stars of jazz would be a part of jazz history. Unfortunately, they are not known to the public, so this is one of my missions. One of the things I was talking about with Alison Brown and some other people is the need for us to do some programs together to showcase our different styles so people can hear it and better understand. That's part of what I what I'm hoping to do

I would have to think that this prize is a real affirmation in that regard. Did you get a call from Steve Martin or was it like the MacArthur or the Willy Wonka golden ticket? Did you think, “Oh my god, this is a joke.” What was the process of getting the announcement about the award?

I was on tour, and I learned about winning while I was waiting to go on stage to give a performance in Sarasota, Florida with my Joyride band, about 20 minutes before the curtain went up. At first I was like, “Oh my gosh, wow.” Then I was like, “Okay, settle down because you have to get on with the show.” I was very excited but it was a special kind of affirmation to me to have this award and acknowledgement from that side of the fence.

Not only does it mean something to me, but I'm hoping that it is a kind of calling card, to enable more collaboration than has happened in the past. I don't want to make it sound like it never happens. It's just that it's not the general way in the music business. There are people who've done this now and then, but we're still so foreign to each other. Alison and I were talking about the whole concept of melody after the program.

Alison Brown is a really accomplished banjoist and I thought, “I’m sure she’s won it.” Then I saw that she's on the committee.

Yes, I'd been wanting to meet her for years and she was here in New York. She was like, “Oh, I've wanted to meet you too.” The reality is that our worlds rarely intersect. I did some tours in Europe where they had banjo players of each style. There was an Irish player. There was a bluegrass player. That's one of the tours I did with Tony Trischka. They wanted to showcase different styles of playing.

I did about three or four of these annual tours. That's the first time I worked with players of these different styles. Then I produced a show at City Winery. I did something called The Hot Strings Festival, which I'm hoping to bring to Lincoln Center as well, where I will showcase different styles. I had Tony Trischka again, Noam Pikelny, and other folks but that’s what I'm hoping to do again which is to bring us together. It would be a focus on diversity and inclusion of the banjo. The award is very important to me. Of course, I'm deeply honored but I also consider it a calling card to move this forward, which I hope I can.

It's interesting because Don Vappie, who when he won it maybe three years ago said the same thing, something along the lines of, “This is an affirmation and although I'm in a different world, I appreciate that recognition that what I'm doing matters.”

Don's a marvelous, marvelous musician. We've known each other for many years. We've played together on occasion over the years and he's a very worthy winner. There are not enough four-string players out there who actually earn a living doing this and touring so I hope that this award supports more people. I also teach, like many musicians, and I try to get more banjo players out there in the world.

You’ve got to find the ones who are asking their parents for a drum set.

Now they would say, “Oh, do what you want.” I have three siblings and they all played instruments and my parents were like, “I'm sorry, we cannot go there.” I showed them. I became a banjo player.

It also came with a cash prize. Is that part of it for you too? That it’s going to help you to do more of this sort of programming that you've wanted to do?

I would say yes, the prize gives me some artistic freedom because it’s not restricted so I can spend my time on this project or that project instead of having to do something else. It's very generous of them since one can use the prize money to pay bills or do whatever.

I've won various honors over the years but this is the first one that's come with a solid cash prize which is very meaningful, of course, to anybody. I am proud of those awards too, but the prize money does make this one extra special.

I was wondering if you could give us a little tour of your banjo? One of the things about the banjo is that it physically is a really beautiful instrument, one that many of us don't even understand.

This instrument is an Ome banjo. Chuck Ogsbury created the Ome Banjo Company, which was only recently sold to Gold Tone Banjos. I understand and respect the decision, still, losing Ome is a loss. We don't know what's going to happen quite yet, but these are what really I consider as the Rolls Royce of banjo instruments. I endorsed them for many years. It's a fabulous banjo. I love this instrument. It has black-engraved chrome, which is sort of cool.

A lot of them are clear in the back, but you actually have a resonator in the back of it, right?

There are two kinds of styles of playing the banjo. One has a resonator and one doesn't have a resonator. Most of the people who play jazz banjo need and want a resonator because your clothes can deaden the sound. We're working with horns and drums which is a whole different thing. It needs power and a sustainable body along with the power to work with this kind of ensemble. I don't weigh that much. I'm kind of small and banjos are really heavy. This is the lightest top banjo I could possibly find.

Speaking of the vintage instruments. I can't play a vintage instrument. They're so freaking heavy. I usually play standing up in concerts. I think this one is eight pounds and maybe that's because I took off the metal flanges here. There was a beautiful wood resonator on the back and Ome was not too happy that I took these things off.

After I did that, they started making snap-off resonators. What I did was I put a piece of plexiglass on the back. Believe me, I experimented back and forth to make sure it didn't compromise the tone. I don't know why It definitely would compromise the tone on different kinds of instruments that I also experimented with but for some reason it worked.

It helps me because it's smaller physically so it suits my size better. I probably got rid of somewhere between half a pound and a pound of weight, which might sound like very little, but it's a lot. I weigh 110 on a good day. I try to stay fit but as I'm getting older, I'm trying to make sure I can still do this. For me, it's heavy. The weight is a thing. There are fabulous historic instruments of the past. I love the way some of them sound and everything, but I couldn't even think of having or using one because I'd end up in the chiropractor's office every week.

Do you use a pick?

Yes, I use Blue Chip picks The kind that I use are WD40 There are different shapes of picks and styles. Initially, I thought, “These artisanal picks are so expensive. I don't know how much of a difference it makes enough to lay out that kind of money.” Now I endorse Blue Chip picks. I think they're awesome. They actually make me feel like I play better with this speed bevel. I won't endorse things unless I believe in them.

I also play GHS strings, and I think they're great. One of the things that I personally do not care for is a thin and bright sound. I like a round full body sound. If you think about it, like rock or jazz guitar versus folk guitar, the jazz guitar has this kind of mellower kind of sound and I suppose there's a mind spillover to this as well. I can't tell you how many arguments I've had with engineers when I would play festivals. We're on a stage and they give me this terrible thin bright sound and I'm like, “That's not right for banjo.” Like, you're telling me what the right sound is when I'm a banjo player.

I like a round, full and resonant sound, in which the instrument sustains beautifully. It has power and body to the sound. I use what are called vintage bronze strings from GHS for the wound strings, which are less durable, but very warm. A big thing is that if I break a string when I'm playing, when I put on one of these strings, it sounds good right away so I’m able to change a string really fast.

Do you want to play something to play us out?

Sure. The first thing people expect is something fast and theatrical. I can do that, but I love tango music which has a history with the banjo. There used to be tango banjos when tangos became a fad and there were tango orchestras throughout the United States. With that tribute in mind, I’ll play tango.

[Cynthia plays a short song on her banjo.]

Wonderful. Thank you so much for playing. It's beautiful. You made it look easy.

It’s a beautiful song that I learned from one of the Louis Armstrong recordings. I love his track of it so much that I decided to learn it myself. I sing too, and with my band we do all different songs and styles of music. I hope people will get into the idea of banjo in unexpected places. If anyone is in the New York area on March 29, come hear The Banjo Experience. I hired every leading banjo player in New York, and I’m bringing up a couple of people from Washington, DC such as Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer. We've got all different styles and I'm having my little mini banjo orchestra and it's free. It's at Lincoln Center in the atrium.

I love that venue. I've been playing there fairly regularly. You can find it online and on all social media. I also want to mention those transcriptions of Elmer Snowden's which are good for guitar, mandolin and banjo, if anyone wants to play any of his kick-ass music. Also, I have this play-along program for anyone of all instruments—trumpet, trombone, piano, violin, whatever it is. If you want to play jazz, I have a swinging group here and this play-along program focuses on the traditions and the styles of our early jazz with some of today's leading players on the track.

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.