DD: This Labor Day weekend, our film critic Harlan Jacobson can’t wait for the upcoming Toronto Film Festival, which starts this wee, to reset the Fall and Winter calendar with new quality films. The summer of 2024 has been a quality film washout, and only a fair box-office season. He has a film, however, that came out of the woodwork to talk about.

HJ: Zero interest in Deadpool & Wolverine, though it made money—less than the top grossing film so far this year, Inside Out 2, but both will likely end in a dead heat soon. After that the junk titles piled up—Dune2, Twisters, Godzilla v Kong, Kung Fu Panda 4 and on and on. Mad Max Furiosa debuted at Cannes and tanked, ditto Kevin Costner’s Horizon. If you blinked you missed the interesting films released in the Summer of 24 – Green Border, Bikeriders, The Films of Powell and Pressburger doc, the small prison drama Sing Sing from Sundance, the Widow Clicquot, the French film about the woman who made good bubbly from Toronto 23, and the restoration screening at Cannes and the US summer release of Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 Japanese epic, Seven Samurai.

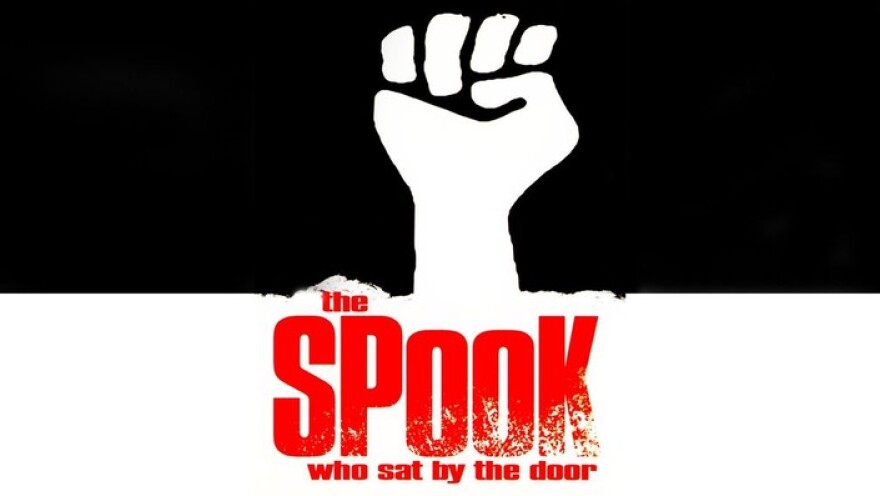

Restorations R Us apparently, as the most interesting film in August heading into Labor Day has been The Spook Who Sat by the Door, a 1973 film by the late actor-director Ivan Dixon, who died in 2009, about a black CIA agent who, after a white Senator has grandstanded about the white country club racism of the Agency, is the sole surviving applicant of a squadron of black applicants. The brass grudgingly makes the “Negro” the Section Chief of the Reproduction Section—meaning he runs the copy machine. After five years of such treatment, the black agent, named of course, Dan Freeman, played by Lawrence “Al” Cook, resigns, he says, to take a a social services job in his native Chicago. That’s his cover story, as Agent Freeman has absorbed enough information about CIA operations and methods to train and launch the Cobras, a black guerilla army to foment a black revolution.

When he left government service in the 60s, Chicago novelist Sam Greenlee, who had been career military and foreign service, holed up in Mykonos to write the novel to reflect the then shift from the civil rights era of integration – Martin Luther King had been shot in Memphis in April of ’68 – past the era of urban riots and into the arrival of organized black resistance: Malcolm X, SNCC and Stokely Carmichael, and the rise of the Black Panthers.

All U.S. publishers passed, and only a small publisher in the UK would publish Greenlee’s book, seeing it in same line as Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and Eldredge Cleaver’s runaway hit, Soul on Ice. As a side note, Greenlee’s original title was the N-Word who Sat by the Door, but Dick Gregory’s N-Word autobiography “took the sting out of it,” according to Greenlee, who changed the title to Spook Who Sat by the Door, to blend the appetite for James Bond stories with the racial stereotype Agent Freeman uses to go undercover to start the revolution.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door has period aspects and production limitations. The two-shot acting scenes and dialogue move with a little too much etiquette—you speak and then I wait and I speak -- the editing of the big scenes by Michael Kahn, Spielberg’s guy on Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, Minority Report, and so on – is gripping. And the Herbie Hancock score gets the jump on the film’s anxiety. But it’s true success is how the story reflects that period in the racial zeitgeist and yet seems so contemporary now.

It was a tough project from the get-go. It met nothing but resistance. No one wanted to fund it except a bank in Ghana, which backed away in a hurry after a visit presumably by white US intelligence operatives paid the bank a visit. Dixon scraped together $$8,000 -- spare change -- to begin shooting, but Chicago Mayor Richard Daley refused permits to shoot in the city. (I’m not surprised at this: When I started my career as a young reporter for Variety in the Chicago bureau, I caught a story that when South Side black audiences started lining up to see The Exorcist in White Polish and Irish west and genteel north sides of town, Mayor Daley told the WB branch manager to get the film open downtown like tomorrow, or there’d be a lot of safety inspections the next day.)

While the journeyman Spook cameraman, Michel Hugo, got some guerilla shots of the Chicago El and the famed back alleys, it was Richard Hatcher, the black mayor of nearby Gary, Indiana, who opened his city to Dixon for filming. In a riot sequence -- following police showing up with dogs after shooting a kid -- that plays like the template for Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing 15 years later, real cops rounded up on camera residents who joined in what they thought was a real riot. Even the enlightened film company, United Artists, known for its socially conscious and highbrow filmmaking, thought they might distribute the film as a blaxploitation film – you know Superfly with a message—but after a strong opening in Chicago, the film disappeared from theaters. It’s now been restored by family, had a run at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and is set for a festival tour in 2024 before playing in theatres around the US in 2025.

That the story by Greenlee, who died in 2014, and script augmented by Mel Clay seems so contemporary is more than just artistic vison. Except for punch cards, the CIA and the military, which broke ground on the use of computing, must have seemed state of the art. And while some larger societal shifts have taken place, racial tension is still in place: Cops still shoot black men and women, but by and large protest and court actions have replaced riots and Panthers. Agent-turned-guerilla general Dan Freeman’s framework for directing action away from brothers and sisters and at the white establishment still holds sway for the moment.