In 1957, I spent three memorable days with Billie Holiday. It was in the unglamorous cinderblock house of my friends Maury and Millie Dell in what was then called the outskirts of Las Vegas. Maury was a piano player from New York who was bouncing around Vegas from hotel to hotel, playing in the “main room” big bands where name entertainers like Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett required top notch musicians to accompany their nightly performances. Maury had worked with Billie Holiday in New York and when she booked a three-week gig at the El Rancho Vegas, it was Maury she called to hire the band. It was hard to find really good players in Vegas and there was a constant demand for guys from New York and Los Angeles to take gigs there, even for a short term—or a short sentence, as the musicians liked to call it—and it was Maury who called my husband, Jules, on a Sunday morning and offered him the lead-trumpet chair with Billie Holiday’s back-up band

Earlier that year Jules, and I had both quit our jobs in Vegas; his with the Ray Anthony band at the brand-new Rivera Hotel and mine in the chorus line of the older and far less impressive Thunderbird Hotel. We returned to Los Angeles convinced that Vegas was a hard place to hold onto any sense of values. Some musicians could only handle it for a limited time before the frenzy of clanging casinos and fake glamour made them long for the more familiar anxiety of hustling for Hollywood studio work. But for others, Vegas was the end of the line. Guys in their fifties would take a hotel gig, thinking it was only for a few months; then, with no other options in sight, they would end up buying a little cinderblock house for $6,000 and settle into that slim desert workforce for the remainder of their careers. That was piano player, Maury Dell.

We became friends with Maury and his wife, Millie, during our stint in Vegas. They were our hipster friends in a town that had very little else to offer. When Jules and I returned to Los Angeles we believed we were finished with that shallow lifestyle. That’s when Maury called asking him to come back. My knee-jerk reaction was, “I thought we were done with Vegas.”

“This is Billie Holiday,” Jules said. I knew what he meant.

A few days later we took off in our black Volkswagen Beetle and made the grueling drive up the I-15 to Las Vegas. Five hours later the gaudy city sprang up like a bad mirage and we were back in the land of fakery.

Part of Maury’s offer came with an invitation for us to stay with them. Their three-bedroom tract home was nestled in the midst of a string of identical houses, each one fronted by cactus and white crushed rock in place of green lawns. We moved in with the Dells and quickly fell into the normal Vegas schedule of going to sleep at four a.m. and rising sometime after noon.

The day after we arrived, the band was scheduled for a late afternoon rehearsal in the El Rancho Vegas Hotel; a well-worn remnant of the days when the mob ruled Las Vegas. At four p.m. the desert sun was still blazing toward the horizon, but inside the El Rancho it was cool and dark, the requisite atmosphere the hotels maintained to make patrons lose track of time and stay glued to the gambling tables.

The band was onstage running down the charts when Billie arrived through the kitchen doors—the same way all black artists did. She came in unceremoniously, wearing dark slacks, her hair wrapped in a white bandana, gave a brief smile to the band, sat down at the piano next to Maury, and went to work.

The rehearsal was a stop and start affair. Billie didn’t sing much, just listened to the band and made comments about phrasing, tempo, how she liked things played. She was soft-spoken and I was too far away to hear what she was saying. Even from a distance I was drawn in by her lack of artifice and how she proceeded with a steady assurance about who she was and what she wanted.

When the rehearsal was over, Jules gestured for me to come backstage. I eagerly followed him into Billie’s dressing room, where a handful of admirers were holding court. She was at her make-up mirror, the worn map of her face illuminated by bare bulbs. Nestled on her lap was a little light-haired Chihuahua, so delicate it seemed to be an external representation of her inner fragility. I tried to break the ice by making some lame joke about how her little dog and I had the same color hair, only the dog’s was natural and mine was not. It was my feeble attempt to apologize for being cute, white and blonde. When I got no response, I awkwardly repeated my lame joke. Billie looked at me in the mirror, a wry smile curling around her lips and muttered, “I heard you.” I could have taken it as a reprimand, but instead I smiled back at her and laughed at my own foolishness. She returned the laugh and that was it. We clicked.

I was a twenty-two-year-old white girl with lots of high-minded ideas and very little experience, and she was a forty-three-year-old Black woman with more life under her belt than I would ever know, and yet there we were, bonding as if we were old friends, not by what we did or said, but by a kind of silence that we shared. A silence in which little was said, but much was understood.

After that we fell into an easy routine of hanging out in her dressing room between shows. Me, Jules, Millie, Maury, and Billie. We’d smoke a joint, shoot the breeze, talk about the crowd, how the show went. It helped her relax. Occasionally other friends would drop by, mostly musicians who were working at the other hotels or just in town for a few nights. Sometimes the room was so tightly packed with men in black gig suits it was stifling and made me think that one of the reasons Billie and I connected was because she craved the relief of some female companionship. It gets lonely on the road.

The late shows at all the big hotels started at midnight and ended around two a.m. Most of the performers were too wired to go straight to bed and would get together at the El Rancho buffet, where they served a “Forty-nine-cent-all-you-can-eat breakfast.” It was a chance for the entertainers to wind down, eat, schmooze, just hang out…but not Billie. After the last show, she would disappear with her husband, Louie McKay, a sharp dresser who, according to rumor, was mobbed-up, (which might explain how she ended up working at the El Rancho.) We never questioned why Billie didn’t join us for breakfast. All the negative press she had suffered made her wary of strangers and we respected her need for privacy. The larger truth was that the hotels had only recently (and grudgingly) lifted their strict color ban when Harry Belafonte bravely marched through the front doors of the Riviera Hotel declaring an end to the unspoken racist policy. Changing the rules didn’t mean changing attitudes and Billie chose to avoid any potential ugliness by keeping low. It was shameful but that’s the way it was.

About two weeks into the gig, Billie’s husband, Louie, tapped Maury after a show to ask a favor. He and a buddy wanted to go fishing on nearby Lake Mead, but he was concerned about leaving Billie alone. Her well documented drug use was in abeyance, but she was drinking enough to maintain a hazy cushion between herself and reality. Louie wondered if we would be willing to have Billie crash with us for a few days. That was a no brainer.

Millie fixed up the other spare bedroom and the next day Billie arrived carrying her dog Pepe in one hand and (despite the desert heat) a heavy fur coat in the other. Louie helped her get comfortable, gave some reassuring words about his prompt return and said his goodbyes.

In the awkward post-arrival moment, no one knew exactly how to treat the new guest. Billie put us all at ease by requesting a little nap and closing her bedroom door. We tiptoed around, trying to act normal while secretly marveling that the musical equivalent of royalty was now sharing our humble digs.

Once we got over our awe and things settled down, we all went back to dealing with the abnormalities of life. It was hard to know what to eat when you woke up in the middle of the afternoon. For Billie, it was just a cup of black coffee to go with her first cigarette of the day. Millie offered to make her a real breakfast, but she didn’t want to be fussed over. The daytime hours slipped by in a deliberate effort to do nothing – just wait for the night’s show: get your head in the right space, save your energy for the long haul. Billie was focused on showtime. She was a pro, she knew the drill.

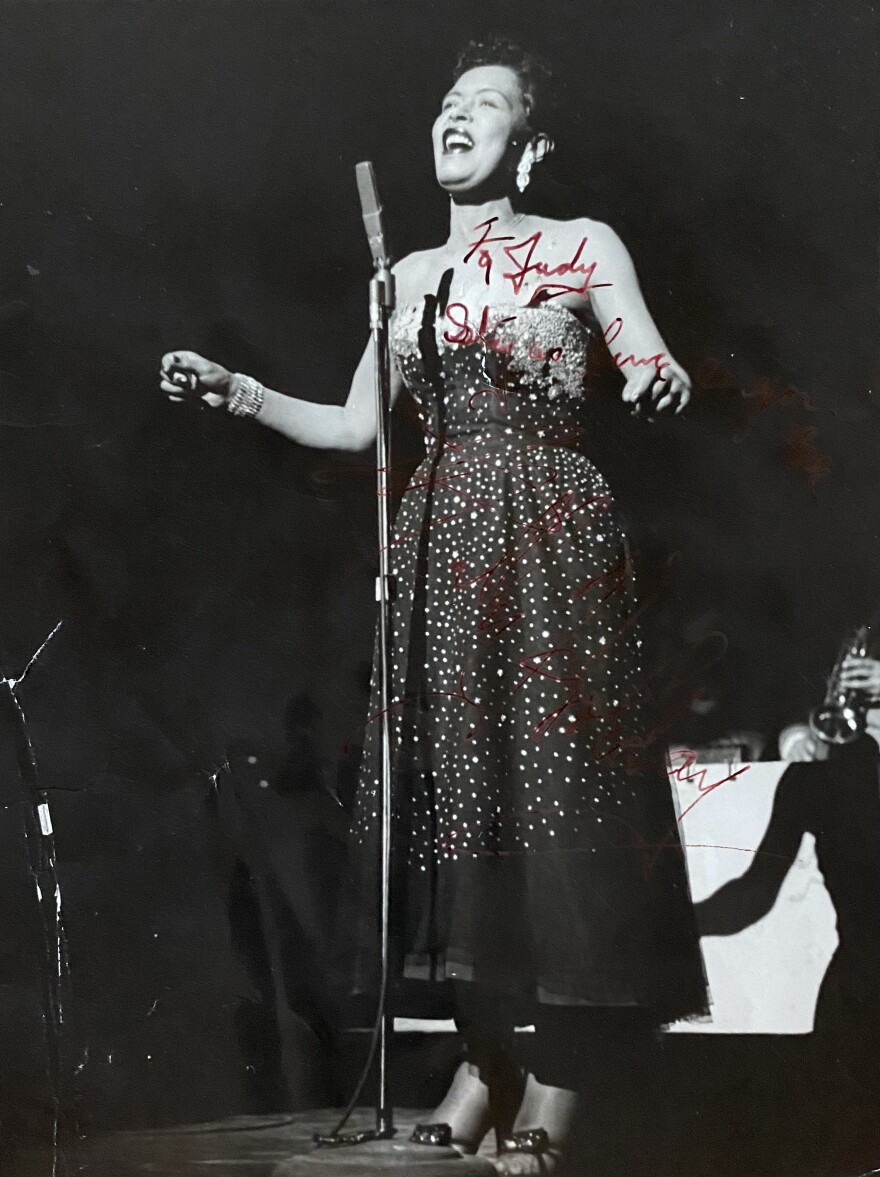

Every night, when Billie stepped on stage with her signature gardenia fixed to the side of her hair, an unusual hush came over the audience. It was unlike anything I’d ever witnessed in Vegas. Even the waiters, usually clamoring their dinner-show trays, found ways to move respectfully. Pinned to the darkness by an icy spotlight, Billie would tilt her head back, close her eyes and with the first strains of “Hush now, don’t explain,” she brought that overblown showroom down to size, made the audience lean forward in their seats, made them listen. In that raucous milieu she was able to create the intimacy of a 52nd street jazz club. She did that three shows a night, six nights a week. It was a hard work.

It wasn’t until late at night, after the midnight show, that she’d let it all hang out. With the forty-nine-cent breakfast out of the question, we’d head back to the house where Millie and I would gather munchies from her well stocked pantry while Jules and Maury hung out in the living room with Billie, listening to some recording by Dizzy Gillespie or Lester Young, and trading musician stories. From the kitchen we could hear her serrated voice recalling bits and pieces of the past.

“You remember that cat from Chicago, played with Dizzy’s band...what was his name?”

“Roy something?”

“No, no. A skinny little guy with a conk…played trombone. Well anyway, one night we were all up at Snookies and this guy....”

She’d go on like, that entertaining us with half remembered anecdotes until she finished off the pint of gin that was her nightly ration. Then while the rest of us satisfied our late-night hunger she’d get down to the good stories. She liked to talk about her time in prison, how she learned to make vodka from potato peels salvaged from the kitchen garbage. She took a childish glee in how cleverly she and her inmate pals were at circumventing the prison rules. Despite all she had gone through, she didn’t speak harshly about the guards or anyone involved with her incarceration. You could sense that in prison, she had found the camaraderie of women who were honored to have her there and who had given her the respect and admiration she deserved.

One night, Billie and I were alone in the living room. She was sunk deep into a black canvas sling chair, the kind that was hard to get out of. I was cross-legged on the floor rolling a joint on the dark wood coffee table when Billie leaned forward and said “I know a song about you.”

“What song?” I laughed, thinking she was about to pull my leg.

She leaned back, closed her eyes and began to sing.

“If her voice can bring

Every hope of Spring

That’s Judy

My Judy”

So there I was sitting on the cracked linoleum floor of a cinderblock house on the outskirts of Vegas at three in the morning while Billie Holiday sang me a love song.

Yeah, I couldn’t believe it either.

“If she seems a saint

And you'll find that she ain't

That's Judy

Sure as you're born!”

She sang from that deep well of emotion that was her trademark, bending the notes, sliding in and around the melody in such a personal way that when she sang my name, it was an arrow straight to my heart.

When she was done, she slipped back into that gentle fog that kept her safe from harm. Her body sagged and her eyes remained closed. The ash from her cigarette had grown long. I took it from her fingers and whispered, “Thank you, Billie.”

The next day, her husband Louie returned from his trip. He’d caught a few fish and was in a good mood. You could see he’d needed that time in the outdoors. It renewed him. He gathered up Billie and Pepe and the fur coat and thanked us for taking good care of his girl. As she left Billie threw back a reminder that it wasn’t over yet. “We’ll see you tonight.” She never wanted the party to end.

On the last night of the gig, Billie had a gift for me. A signed photograph with the inscription “To Judy, Stay as fine as you are…Love Billie.” I had nothing to give her but my never-ending devotion.

Not long after that, she died. The bad drugs, the prison vodka, the nightly bottles of gin, they all contributed. But it was the cruelty of life—hurt piled upon hurt—that finally did her in. When I learned of her death I was not surprised.

Some musicians dazzle us with their artistry, others entertain us with wit and style. Billie’s genius was teaching us to feel...more deeply, more caringly, and more honestly. She changed me with her music and her love, just like she’ll do for anyone who’s ready to listen.